Juneteenth 2025: No time to let the guard down

During the White House ceremony on June 17, 2021, when President Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, the first vice president in U.S. history, Kamala Harris, stated: “We are gathered here in a house built by enslaved people. We are footsteps away from where President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. We have come far, and we have far to go.” She added: “But today is a day of celebration. It is not only a day of pride. It’s also a day for us to reaffirm and rededicate ourselves to action.” Little did she know that the gains of decades of Black people’s fight for civil rights would be under attack a shy three years later, prompting civil rights organizations to sue to stop Donald Trump from turning back the clock.

Today, June 19, 2025, is the fourth official celebration of Juneteenth, a milestone in African American History. President Biden signed the holiday into law after a heavy push by the African American community. Though the celebration is not new, making Juneteenth a federal holiday is helping it gain popularity.

On January 1, 1863, as the U.S. civil war—with the debate about the end of slavery at the core of it—was about to enter its third year, President Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared free all persons held as slaves. The earth-shaking news triggered understandable jubilation among enslaved men and women who gathered in churches to celebrate. However, the president’s decree could not be implemented in states under the control of the rebellious states, the westernmost Confederate state of Texas being one of those.

But, on January 31, 1865, Congress passed the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in the United States. Two months later, General Robert Lee, the commander of the Confederate army, surrendered. Within two months of the defeat of the Confederate army, General Gordon Granger of the Union army, leading some 2,000 Union troops, arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas and informed the approximately 250,000 enslaved people in the state of Texas that they were free. The newly freed men, women and children named the day “Juneteenth.” It also came to be known as “Juneteenth Independence Day,” “Freedom Day,” and “Emancipation Day.”

Even before it became a federal holiday, Juneteenth was celebrated nationwide throughout the Black community. It is marked with prayers and family gatherings, including pilgrimages to Galveston, Texas by formerly enslaved people and their families. Over the years, Black leaders pushed hard to make it a federal holiday. The injustice inflicted on the Black community, as exemplified by the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in the summer of 2020, triggered massive multiracial protests nationwide despite the Corona virus pandemic and gave the fight new impetus. It led to President Biden signing the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act.

The cruelty of Black History

Despite the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln, it would take another century before the adoption of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson to break down the legal barriers at the state and local levels that prevented African Americans from exercising their right to vote as guaranteed under the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The long wait from the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 until the Voting Rights Act a full century later is a slap in the face of the immense contributions slaves have made to the very creation of this nation.

Enslaved people’s contribution to building the U.S. economy has been documented by many a historian contrary to a few who initially described such contribution as rather minor. In an essay titled “Historical Context: Was Slavery the Engine of American Economic Growth?” published on the website of The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History by Steve Mintz, a white American historian at the University of Texas at Austin, the scholar writes: “In the pre-Civil War United States, a stronger case can be made that slavery played a critical role in economic development.” He also writes: “One crop, slave-grown cotton, provided over half of all US export earnings. By 1840, the South grew 60 percent of the world’s cotton and provided some 70 percent of the cotton consumed by the British textile industry.”

Enslaved people did not only contribute to the economy of the U.S. South. A variety of businesses that flourished in the industrial North provided services for the slave South: textile factories, a meat processing industry, insurance companies, shippers, and cotton brokers.

Fighting to save the union

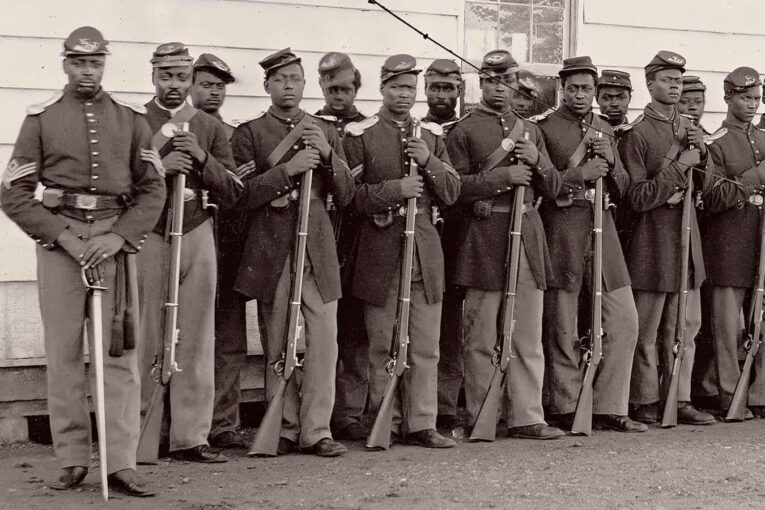

In addition to being the economic engine of the South, slaves also contributed to saving the union by fighting during the Civil War and providing the much-needed logistical support to win the war. There has been an abundance of literature on this subject over the years. However, because of the fluid nature of the study of history, a story that appeared as recently as September 2017 on the website of the National Archives provides compelling details with exceptional clarity.

The story, titled “Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War,” shows how thanks to the push by African American leaders such as Frederick Douglass (whose sons contributed to the war effort), African Americans enrolment, slow at first, increased, especially after the government established in May 1863 the Bureau of Colored Troops. By the time the war ended in 1865 with the crushing defeat of the Confederate Army, Black soldiers accounted for 10% of the U.S. Army. That was roughly 179,000 men, with another 19,000 serving in the Navy. According to historians, Blacks’ services in the artillery and infantry and in all non-combat support functions—carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters—were valuable contributions to the war.

More than a century and a half before Colin Powell, sixteen Black soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest military honor, for their valor during the Civil War. In 1863, Harriet Tubman headed an espionage and scout network for the Union Army, providing crucial intelligence to Union commanders about Confederate Army supply routes and troops. She also helped liberate enslaved people to form Black Union regiments. Kate Clifford Larson, a visiting Professor of Women’s Studies at Brandeis University and a bestselling author of critically acclaimed biographies, including “Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero,” writes that “in early June 1863, [Tubman] became the first woman in U.S. history to command an armed military raid when she guided Col. James Montgomery and his 2nd South Carolina Colored Volunteers Regiment along the Combahee River.”

The long road to real freedom

Clearly, the abolition of slavery did not actually set enslaved people free, despite enslaved men and women’s and their descendants’ contributions to building the United States. For a century, they were treated like social pariahs by a cruel racial segregation system. Jim Crow Laws, which mandated racial segregation in all public facilities throughout the former Confederate states and beyond, literally dehumanized Black people. The terror stoked by the white supremacist terrorist group Ku Klux Klan and loosely organized white mobs hanged, burned, dismembered, garroted, and blowtorched Blacks and other minorities.

Thanks, however, to the hard work and the suffering of the former slaves and their descendants, along with the welcome support of non-Blacks of various backgrounds, the long civil movement brought the freedom the Black community enjoys today.

The “grandmother” of Juneteenth

A retired teacher, 96-year-old activist Opal Lee, a native of Texas, has led the movement leading to making Juneteenth a national holiday. Every June 19th, the woman known as the “grandmother of Juneteenth” leads a 2.5 miles march in memory of the historical landmark. The number 2.5 symbolizes the two and a half years it took for Texan slaves to be free after the Emancipation Proclamation. Lee also encourages African Americans in other parts of the country to mark the occasion by organizing their own marches to underscore the notion that “we are not yet free,” and raise awareness about the importance of understanding that freedom is for everyone.

“We have come far, and we have far to go,” said Vice President Kamala Harris during the signing by President Biden of the National Independence Day Act on June 17, 2021. The Trump administration’s attack of Diversity, Equality, and Inclusion programs during the first week of his return to the White House underscores the vice president’s warning of sorts, just as it justifies her call, “It’s also a day for us to reaffirm and rededicate ourselves to action.”

The uneven pace of progress

It’s believed that the Black civil rights movement was triggered in the summer of 1955 by the fact that a Chicago African American woman, Mamie Elizabeth Till-Mobley, invited the press to see the open casket containing the gruesome remains of her 14-year-old boy, Emmet Louis Till, who was abducted, tortured and lynched to death on August 28, 1955, while vacationing in Mississippi, after being accused of whistling at a white woman. The horrible sight shocked the press which relayed it to the world, thereby bringing awareness about the persecution of African Americans at the hands of racist America.

Then followed on December 5, 1955 (the same year) the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott triggered by the adamant refusal of a Black woman, Rosa Parks, to give up her seat to a white person as required by the local racial segregation laws. The protracted boycott ended one year later when the United States Supreme Court declared on December 20, 1956, that the Alabama laws that segregated buses were unconstitutional.

Then came five decades later, after the indisputable gains of the civil rights movement, the stunning wave of anti-Black racism that surged out of nowhere after the election of the first African American president of the United States, Barack Obama, in 2008. To those who were surprised, and in comments about the result of an Associated Press opinion poll posted on the web on October 27, 2012 showing that prejudice against Blacks went up after Obama took office, William Jelani Cobb, an African American author, professor of history and one-time director of the Institute for African American Studies at the University of Connecticut, said: “We have this false idea that there is uniformity in progress and that things change in one big step. That is not the way history has worked. When we’ve seen progress, we’ve also seen backlash.”

Translation: Trump’s attempt to turn back the clock will pass. But how much damage would he have done to the Black Civil rights movement for which Blacks, with the support of others, have fought and died for?