In Uganda, When JFK Was Shot

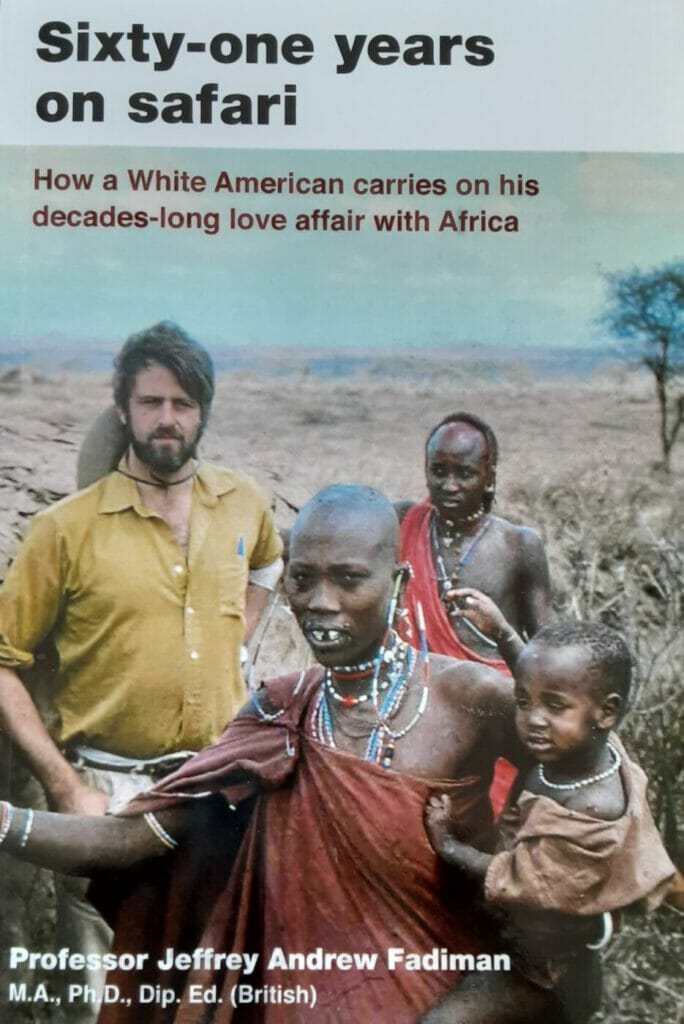

BY PROFESSOR JEFFREY FADIMAN

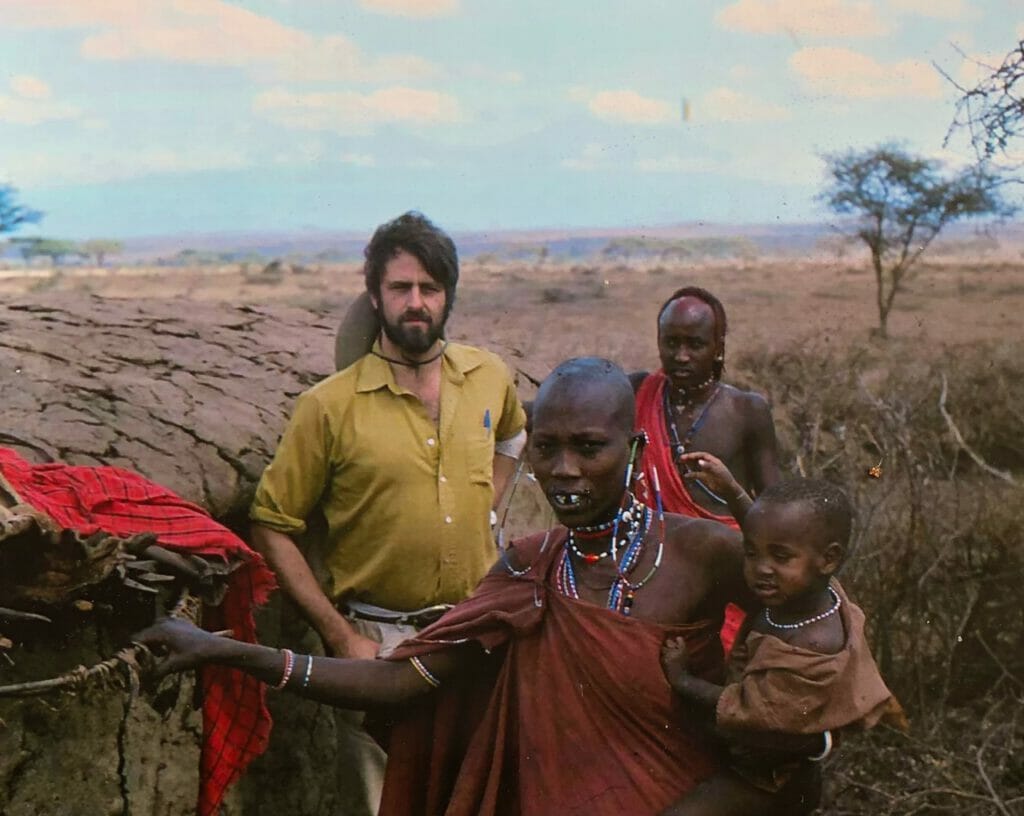

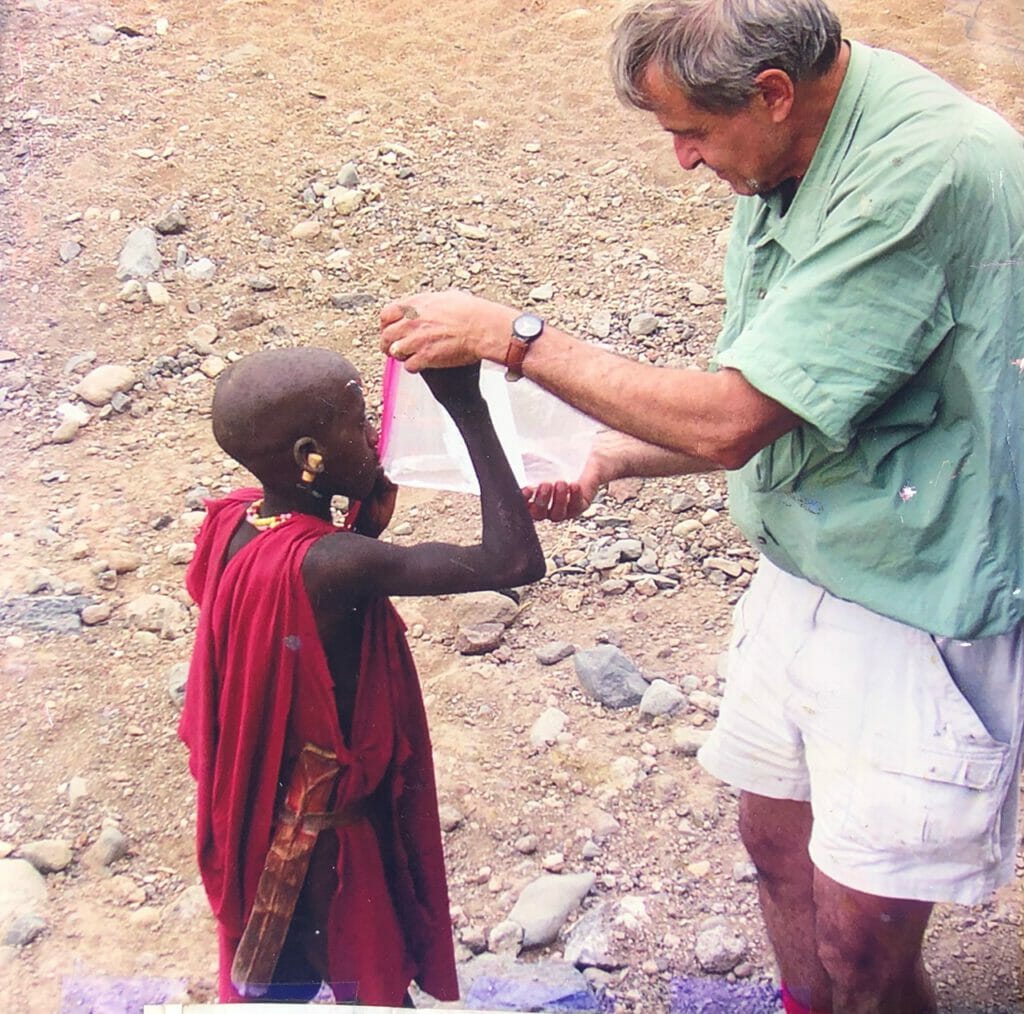

In his just-released book Sixty-one years on safari—How a White American carries on his decades-long affair with Africa, Professor Jeffrey Fadiman who teaches Global Marketing at San Jose State University in California, shares his extraordinary first-hand experiences in Africa. The following segment focuses Uganda.

President John F. Kennedy was assassinated while I trained to become a secondary school teacher in Uganda. My wife and I lived in a cluster of three European houses. We were surrounded by African huts, each surrounded in turn by groves of banana trees. Huts and groves extended off into the distance in every direction.

We had hundreds of African neighbors. Thus, our home was filled with an unending ebb and flow of African sounds. Dogs barked. Cows mooed. Roosters crowed. Women and children laughed and sang and teased as they walked past. We owned a dog named “Jambo”. (“Hi”) and the men called out “Jambo” to the dog as they passed, to see if they could make her wag her tail.

One afternoon, however, I walked out of the house into dead silence. Nobody sang. Nobody laughed. Nobody greeted. Even the dogs were quiet. A bit scared, I had time for only one deep breath.

Then, the drums began. The sounds came from every direction, not one unified beat, but loud and compelling all the same. They were obviously calling people to come to them because everyone flowed in whatever direction a drum growled.

Gradually the flow reversed itself. The people all formed into ragged processions, elders at the front, followed by drummers. It was scary. No one was dancing, laughing, singing. Nor were they angry, cursing, waving spears. They all just walked and they were walking towards me. I called my wife and our two American neighbors. By unspoken agreement we all stood next to our cars, uncertain what to do. If they were angry, we could jump in the cars and leave. As they came near, however, we did hear them singing—softly, slowly, sadly.

As the groups flowed into our yards, I saw that everyone was crying. An elder stepped forward and took both my hands.

“Your President has been shot and killed. We came to sit with you.”

Six decades later, I remember every second of what followed. The news hit me like a fist in the stomach. I doubled over, then staggered backwards into a chair. Sitting, I remember thinking that I had 100 guests in my front yard, and I had better stand up and speak to them. I stood, thanked everyone for coming to inform me, then asked them to forgive me if I went into the house to be alone.

What I wanted was to be alone and cry. What I heard changed my life: “Do not go (and be) alone,” the elder implored. “We have been told that when someone dies in America, everyone sorrows alone. In Africa, when someone dies, we all come to sit with his kin and sing. The pain grows less when we sit together and hold each other and sing as one.”

The elder was right. At first, I did go into my house to cry. My 100 neighbors all sat in my yard and softly sang. Some songs were Christian, many with English words. Others were in luGanda (from Uganda’s Ganda tribe), often repeated, thus easily remembered.

I listened. I knew the English hymns and some luGanda words. The singing drew me outside. I shyly joined my 100 neighbors and was welcomed. I sat with everyone. Two different people held my hands. I sang softly, and because I was not alone and people held me it hurt less. The sitting, the songs and the holding changed my core idea of Africa. Before, I had come to Africa to teach Africans. Now, I saw that in matters of kindness they were teaching me—and that their way was better, kinder. From that day—the day Kennedy died—I realized that I had come to Africa to learn from Africans.

____________