In Africa on foot—Sharing safari guides’ wildlife secrets

By Professor Jeff Fadiman

Was it really only 60 years ago? I had just left college. I was tall, slim, black bearded, intensely single and taking my first long look at Uganda—a country of 1,000,000 banana trees. I was stunned. A whole, beautiful country about which I knew absolutely nothing! I was out of my mind with eagerness to learn all about it.

I had been chosen to live in Uganda, Kenya, or Tanzania for three years by “Teachers for East Africa,” a U.S./U.K. program that was eventually absorbed by the American Peace Corps. Their goal was to choose 20 American college graduates, train them for one year, to teach, then put them into British African schools for two years. Three years in Africa was a big commitment. I had left my family, girlfriend, and dog. For what seemed like forever.

When I started teacher-training, I met Old John. Old John Wetherby was old, thin, and very British. He had lived in Africa forever and was known as “An Old Africa Hand.” In classes he was also aways British proper. On weekends, however, he transformed himself into “Tarzan of the Swamps.” His rifle lived in his car. Each weekend, he took it and simply walked into the huge, Mabamba Swamp. When he appeared, Mabamba Africans were waiting. They carried spears and knew every inch of every muddy trail. However, since John carried the gun, he could shoot the Mabamba Sitatunga.

A sitatunga is a swamp antelope. It is brown, has longish horns and huge, splayed feet, which allow it to navigate the swamp. If scared, it hides under water, with only its nose sticking out. Then, it silently swims to a safer place. John’s weekend work was to silently follow the Africans as they tracked semi-invisible hoofprints until they found a sitatunga. His next job was to shoot it. The Africans cut it up, then carried the pieces to their village. They sang all the way, often songs in praise of John. Once home, they would roast and eat—saving a huge piece for John to carry home.

John would then return to school, become proper, and teach. However, I completely lost my mental balance. No longer was I willing to be plain, dull Jeff, the standardized Los Angeleno whose most adventurous act had been to boogie board. NO! I would become a (rather young) Old Africa Hand. I would trek the Mabamba swamp, follow Africans as they tracked hoof prints, then shoot a sitatunga. Thereafter, I would listen to their songs about me, eat roasted sitatunga and stay in Africa forever.

Shoot to miss

My first step in realizing this dream was to shyly ask John if I could join his next swamp weekend. He asked if I could shoot. I said “yes,” and was invited. The adventure rolled out as I had imagined —until it all went wrong. There I was, plopping my feet through the deep, gluey mud. Then, John whispered, “Jeff, sitatunga. Shoot!” I can shoot. As a soldier, I hit targets at 500 yards. This one was at 50 yards, standing and looking at me with big brown eyes. C-a-r-e-fully, I followed my army training, aimed, shot, and missed. The sitatunga ran, flashing through the swamp grass. I was cool. I had time. I aimed, shot, and missed again.

John then shot the racing sitatunga at long range. I just stood there, asking myself, “why?” Of course I knew. I didn’t want to kill it! I didn’t want to kill anything wild and free. I just wanted to look at them and maybe pet one if I could. That was the first lesson I learned from Old John—that life is better if you miss your shot and thereby help to fill the world with living animals, especially wild animals.

I walked out of the swamp listening to songs that praised John instead of me. Eventually, I learned to sing one, and was satisfied. The African bush had taught me a first lesson: shoot to miss.

How to get close

My second lesson came from another guide—also old and named John. We were at our breakfast fire when an elephant strolled by. “Do you want to go and talk to it?” John asked quietly. I said yes but meant no. So did my U.S. companion. Both scared, we rose and timidly followed John as he walked up to the elephant.

John walked slowly, cooing at the elephant as he moved in. We both hung 10 feet back, each calculating the number of seconds it would take to reach the car if it charged. John stopped, as the elephant swayed, grazed, and ignored him.

“Now watch,” he whispered to us, and took one more step. The elephant exploded. The trunk went up. The ears went out. The trumpeting shook the trees. Worse, the elephant charged. John faded backwards with his eyes on the elephant, but retreating. We did the same. The elephant stamped, flapped its ears, trumpeted, and then stood still.

“Gentlemen,” John said softly, “that was a mock charge. What he was telling us was that we had come one step too close and to get the hell back.” We did. Second lesson: most “wild” animals offer no danger. All they want is for humans to keep a proper distance. They charge when we miss the message.

When to get close

Too early the next morning, John took us walking—to see lions. “I live near a pride of nine,” he said. “We’re friends. I walk out to see them most mornings. Want to come?” “NO!” I thought. “Yes” I said. So did my friend. We walked. The sun rose, hoofs thudded, birds sang, and I was scared. I felt that my life was now in the hands of another person. If he finds lions and then has a stroke, I am as dead as him. Even if lions chase me up a tree, I can never find my way out of this bush. Why do I pay money to risk being eaten?

We walked up a ridge. John dropped quietly to his belly at the top. He gently called out “ooooooahhhh” several times. No response. I peeked over the ridgetop. Nine lions looked quietly back at me. My first thought was to dodge back. My second thought was “They’re all golden.” And they were, semi-sleeping in the golden sun. I just watched them watch me. Sometimes they yawned at me. Why didn’t they eat me? That’s what lions are supposed to do.

John explained it later. “Lions hunt at sundown. They stalk, kill and eat until dawn. Then, they drink a lot of water. Bellies full, they look for shade. They sleep through the day, until they hunt again. That’s why we can watch them now. Lions can be quite safe in the mornings. They are too sleepy to bother chasing and biting you.” The lion lesson: when you see them matters. To get close on foot, come at dawn, when they are sleepy and safe.

In rivers, become a ball

My final lesson came from a younger Zulu guide named Bafana. He wore bush clothes but had a medal on his chest. “It is a medal of honor from the nation,” he said. “I got it for saving a White tourist who had ignored my warning regarding hippos and crocodiles. Please don’t you ignore it.”

I was part of a two-man canoe trip down the Zambezi River. Bafana, in a second canoe, was to lead us through unending herds of hippo and canoe-biting crocodiles. As he explained how to deal with crocs and hippos, he told us the story of the medal—to warn us what can happen to clients who disobey their guides.

“That fellow was a Swede. We camped on an island. I told him not to go even near the water—that a croc could come out and chase him down. He went swimming anyway, but asked his wife to watch for crocs, not knowing they swim under water.

A big one grabbed his foot. He and his wife screamed. Other tourists came running. They hurled huge rocks onto the croc. Ignoring them, he began to twirl the man to drown him. I did what I could. I swam out and grabbed his tail. He dropped the client and tried to get me but couldn’t reach. He whipped his tail back and forth so that my hands began to bleed. Luckily, one tourist hit the croc’s head with a huge rock. He stopped and floated. I dragged the Swede ashore. Now, may I ask you not to go near the water?” I was persuaded.

Bafana then taught us what to do if we did fall into the river: “Hippos walk underwater. If a canoe passes over one, it casts a shadow that scares it. Instantly, it lunges up and tips the canoe. If you are tipped, become a ball. Put your arms, legs, and head against your chest. A hippo will bite and break an arm or leg but not bite a human ball. Once you are a ball, just drift. The current will take you towards the shore, and I will come with the canoe and a sharp paddle. If a croc finds you, I jab its eyes.”

Outwardly calm, but an inner closet coward, I began three days of paddling. Hippos were everywhere, but not even one tipped my canoe. They were, however, still scary. Hippos leave the river to graze inland. If scared by anything, they race back towards the river and safety. If the riverbank is steep, they lunge off the edge and splash— all 9,920 pounds—into the water.

It does not go well for the canoeist if the lunging hippo lands on his canoe. Nor does it go well for the closet coward who spends his three days on the river watching hippo’s take off and land—either just ahead or just behind him. Splash! Splash! Splash! For the professional worrier, it is hard on the nerves.

Some wildlife secrets

Sadly, all safaris end, and my lifetime of safaris may have ended forever. As I look back over that lifetime, it does seem as if the guides have taught me wildlife secrets:

- If on foot, shoot to miss. Africa becomes vastly more exciting when you experience it on foot. In thick bush or elephant grass, to feel sure that nothing dangerous comes near, you use not just vision but also hearing and smell! You will never have felt so alive! However, most of Africa’s “wild” animals are not dangerous. On seeing us, they have three options. One is to flee. The second is to mock charge to make us flee. The third is to stand still and stare. None of these options are dangerous, particularly if you are on foot, holding a gun. If you must shoot, shoot to miss. They will run. You will live, but so will they.

- If on rivers, obey the guide. Hippos kill far more humans (500 people per year) than lions (200 per year). Crocodiles kill any human they can reach (1000 per year). Tiger fish can bite the hand that fishes for them. Calm water can hold bilharzia flatworms—so small that they enter the pores in our skin, then migrate to our blood vessels. Ask the guide how best to survive—and do it.

- If on foot, move in close. Most of us on foot want to get close to wildlife. The steps are the same whether you stalk an elephant, zebra, or porcupine. First, ask the guide how close you can get. Next, believe him. Third, follow him slowly, and silently. Keep your hands still, with arms and eyes down. Never make eye contact. Often, the animal will just stand and stare at you. If it moves, stop and edge back. One step more and it may flee or mock charge. They charge because we scare them. Even hippos are scared into action by the shadow of our passing boat. Don’t take that final step. Just watch and admire.

- When with predators, come at dawn. Predators hunt, kill, eat, and drink until shortly after dawn. If walking, visit when they are full, sleepy, and seeking shade instead of you.

Imagine a wildlife-filled world

Most of us want to get close to animals—especially wild animals. We all want to pet puppies and rabbits. We love to watch deer cross a road. In Africa, we glow when wild animals come close. We want to pet them—especially lions. For reasons none of us understand, we always want “them” to interact with us. Thus, we like dogs and blame cats for not wagging their tails. Our lives grow richer when they wander into our world. Why not wander into their world—in Africa, on foot.

To read more articles by Prof. Fadiman, click on these links

In Uganda when J.F.K. was shot

Reconstructing Black Africa’s golden past

To buy Professor Fadiman’s books, click here

___________

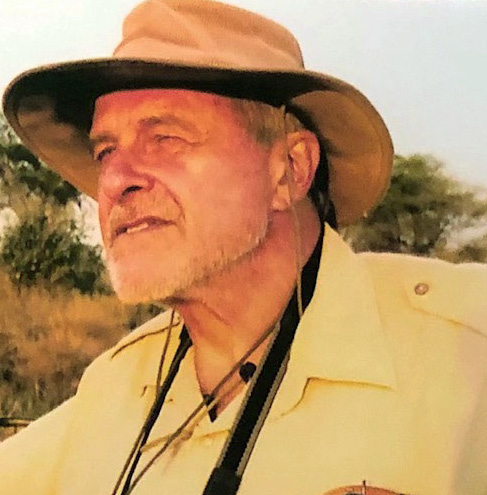

About the author

Jeffrey A. Fadiman is a professor of Global Marketing at San Jose State University in California, and a Language and Area Specialist for Eastern and Southern Africa. A graduate of Stanford University with two years at the Universities of Vienna and Free Berlin, this Fulbright scholar taught both U.S. and global marketing tactics at South Africa’s University of Zululand. He first experienced Africa in 1960 by canoeing up the Niger River to Timbuktu. Thereafter, he lived in Meru, Kenya, where he rediscovered the traditional history of the Meru tribe, which had been crushed by British Colonialism. Fifty years later, the Meru accepted him as the first White Elder of their nation. Professor Fadiman has supported both Tanzanian AIDS orphans and the schools to which he sent books, pens, paper, and hope.