Africa’s children need guardian angels

How to adopt an entire African primary school

African schools are poor, especially in rural areas where they often lack the bare minimum: teachers, school supplies, even food and water and a roof. Jeffrey Fadiman, an American university professor and philanthropist who fell in love with Africa six decades ago, shares his experience helping African schools—a guide for others.

BY JEFFREY A. FADIMAN, PH.D.

Photographs by Lara Hollblad-Fadiman

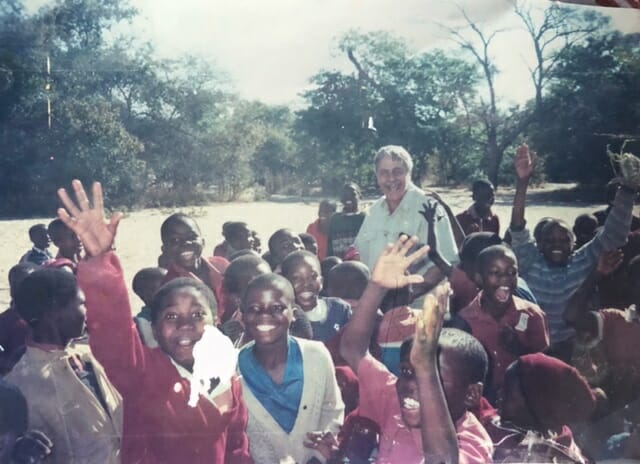

I became a Guardian Angel in an African thunderstorm. I was in Zimbabwe, leading 20 students on safari. We were in the bush; it looked like rain. The driver suggested we pull into a bush school. We did. Ninety kids poured out of holes in the building that were once doors and windows. They surrounded us, laughed, yelled and shook hands. My students hid timidly behind cameras, taking pictures instead of making friends. Then, after my teasing, they grabbed our soccer balls, jumped out and everyone played.

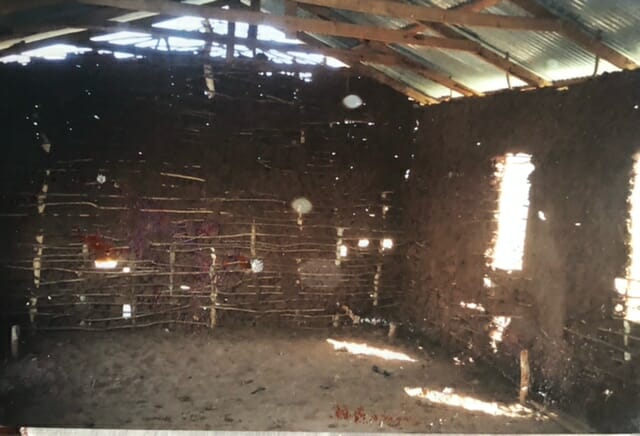

And then, how it rained! Lightning snapped, thunder boomed, and the kids stampeded back into the school, holding our hands. With no doors and windows to close, the rain followed us in. We stood in the back, dry. The pupils sat on the floor, getting rained on. No chairs? No desks? No pens? No paper? No problem! The teacher chalked a lesson on the blackboard: short words in English.

The kids both shouted the words in unison and pretend-wrote them on the floor with one finger. Everyone had a wonderful time. Except us! We were all horrified. Nothing to read? Nothing to write with? Nothing to write on? My students turned on me: “Couldn’t we help? Some of us did. Some still do. Over time, we evolved into Guardian Angels.

HOW ANGELS GROW WINGS

Real angels are born with wings. Not us. Our wings grew only when we talked with the kids, after classes. We learned that:

- 20% were AIDS-double-orphans, having lost both parents.

- None ate breakfast. Each rose at dawn, then marched (in groups) two hours in the bush to school, singing and shouting to scare off hyenas.

- None ate lunch. Thus, they faded each afternoon. The question ”toilet please?” was code for “I give up.” They slipped outside and lay down till school ended.

They marched home in shouting, singing groups, then ate porridge by firelight, filling but tasteless. No one studied after supper. Flickering firelight, and non-stop talk stopped it cold.

Zimbabwe has 1.8 million orphans—26.6% of all its children. So what? Statistics don’t move us much. However, people-storied do. Consider Paulina, who lost all 12 of her own children to AIDS. At age 91, she adopted 16 of their grandchildren. Consider Charles, who lost both parents to AIDS, moved in with an uncle, then lost him too. He moved to a grand mother, but she died. By then, his neighbors viewed him as cursed, and no one took him. These stories move us all.

When one African child loses a dad, it means economic catastrophe, since the wage-earner is gone. Since most mothers don’t work, it means semi-starvation. To lose both parents must be so overwhelming that I can neither imagine nor write about it.

Nonetheless, that day we met many such children. One lived in the bush, stealing two bananas per day (“One for me, one for my sister.”). One sling-shot birds off telephone wires to cook and eat. In a “children’s village” (where all adults had died) ten-year-olds cared for-six-year olds, who cared for toddlers.

These children need a sanctuary; a place that offers friends, supervision, things to do, things to learn and even hope. To me, that means a school. But the schools themselves are semi-starving. Many have only teachers, blackboards, and chalk. Some have trickles: one schoolbook per ten students, or ten shared pens in a hundred-pupil class. None have “enough” of anything at all.

Once, I visited a very old chief. He had 14 wives and 93 children. Undaunted, he built them a school: Walls, roof, floor, and teacher. That was all. No blackboard, chalk, paper, pens, etc. Do you see where a guardian angel might help?

WHAT WON’T WORK:

Giving Money Won’t Work

Too many African primary schools receive too many ten-minute visits from too many tour groups. These enter a class, are shocked by what they see, take the obligatory pictures and—often—donate money to a teacher. Now, the teacher has a problem. African teachers are poor. African traditions call for “windfall wealth” to be shared among one’s group—here, other teachers. Often, they do share. Or, recipients may pocket the cash. I have even visited “fake” schools where happy children sit in singing rows for tourists to admire, photograph and fund. Donations do nothing for school kids! Adults take them. Giving money won’t work.

Sending US books won’t work

Often, tourists reach home quite moved by what they saw. They respond by collecting U.S. primary school books and mailing them off. This won’t work either.

One reason why is because no tourist asks if the children can read. Many kids speak English, but few read it. To read, they need lots of books, available over lots of time, with which to practice. These kids have no books, ever.

A second problem is cost. Mailings to Africa cost so much that your book package may end up smaller than when you start. Many classrooms hold 100 pupils. It is expensive to supply 100 students books plus one for the teacher. That lets kids learn one subject—say, Math. However, each pupil needs books for six subjects. That’s 606 books for one grade. Most primary schools have six grades. That’s 3,636 books. Does that seem expensive?

A third problem: your book package may “magically” vanish on arrival. This is Africa. Books are valued. Sometimes, overseas packages marked “BOOKS” just disappear. If they do arrive, however, a customs official will charge duty. That means each headmaster must pay “something” to retrieve your books. That won’t work! No headmaster, overworked and underpaid, can pay any duty whatsoever. So, your packet never leaves the post office.

The final barrier may be the headmaster himself. Those I meet love books. Thus, their first idea may be to protect them. Some lock them in a cupboard, or pile them in their office and lock the door. Rarely have I seen donated books displayed for the children to choose. Books out of sight: books out of mind.

Nor, will every headmaster want the books you send. Some reject them—especially fiction—stating that pupils need only read what must be memorized for government examinations. Other headmasters take the books home–to read first to their children, then pass to neighbors until they disappear. In sum, donating books won’t work.

WHAT MIGHT WORK: A PRIMARY SCHOOL SAFARI

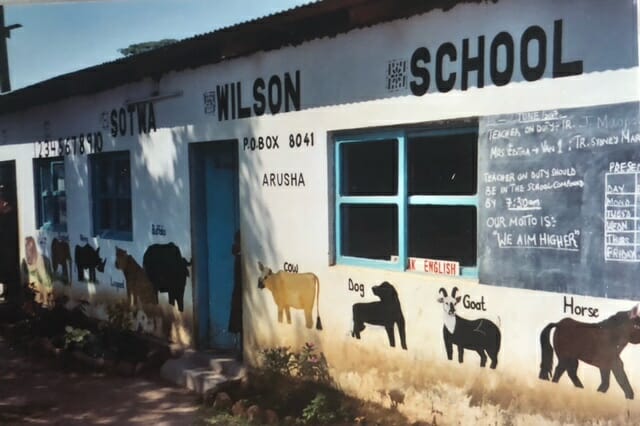

What might work is to go to Africa! Play guardian angel. To play it well will take your next two vacations. Start by reading. Find African regions (not countries) that excite you. Choose one you might learn to love. I fell in love with Kenya’s Mt. Kenya, Tanzania’s Maasai land, and Zimbabwe’s Victoria Falls. You might do better.

Then, go on a primary school safari. “Safari,” in Swahili, means “a trip.” Start by exploring. If in East or Southern Africa, look for lions. If in West Africa, visit villages or wander the cities—surrounded by clouds of smiling, shouting little boys.

As you travel, talk to every African you meet. On my safaris, I talk to guides, waiters, bartenders, wood carvers and everyone else I see. I always ask one question: Do you know a primary school that needs help?

EVERYONE has a school they want me to visit. Everyone wants to lead me there. Everyone swears that “their” school is desperate. Of course, these guides lead me to schools containing their own children. That’s fine! The father already known is welcomed by the teachers, who are then happy to meet me.

Wildlife guides are the most enthusiastic. Each has school-age children. Each knows tourists who visit Africa, watch animals, take pictures, and ignore Africans. The best save wages to build their own primary schools, brick by brick and teacher by teacher. They will become your allies, suggesting contacts, arranging meetings and translating as you talk.

Your goal is to generate these contacts. If someone introduces you to a headmaster, sit down, ask questions and take notes. I start by asking each headmaster his/her greatest problem in educating pupils. They always say they have far more children than they can educate, and no school materials with which to teach them.

That leads into increasingly precise discussions as to “exactly” how many books, pens, sheets of paper, maps, rulers, chairs, tables, doors, windows, and even food and water they wish they had but don’t. Somewhere in those discussions, you will find a place to start.

ADOPT ONE SCHOOL

Before you enter a new school, bring a secret weapon. Bring 10 flattened soccer balls from America. Ask your hotel staff to pump one up each morning. As you enter a new school, pull out a soccer ball. Then stand up outside the car so the kids can see you. Enjoy the next three minutes, when every child boils out of school to surround you.

Greet them, then hold up the ball and shout WHO WANTS TO PLAY SOCCER?” Then, kick the ball. Every kid in the school will chase it; every teacher will smile and you will feel very welcome.

Visit several schools. I visit those in the bush, but you might prefer schools in city slums, in towns, or high on volcanos. Choose one school from those you visit; perhaps the one that charms you most, has the best headmaster, sweetest kids, or most devoted staff. Or, choose the worst—deepest in the bush, fewest school supplies, absent headmaster, dispirited teaching, hungry pupils, or just the place that needs some help. Adopt it.

Meet the headmaster, head teacher and 1-2 other teachers. Interview each. My first statement is always the same: “I would like to help this school—ideally for a long time—but do not know how. I would like to learn anything you can teach me about how the school is run.”

My first question is always the same. “What is the greatest problem you face in educating these children?” The answers can take an hour. They face so many problems that every educator feels overwhelmed. I ask more questions, take notes and gradually create a picture of which items they need, how many of each, and the probable cost. They often speak in anger. These are passionate educators, committed to both educating children and aware that they can’t! They lack the tools.

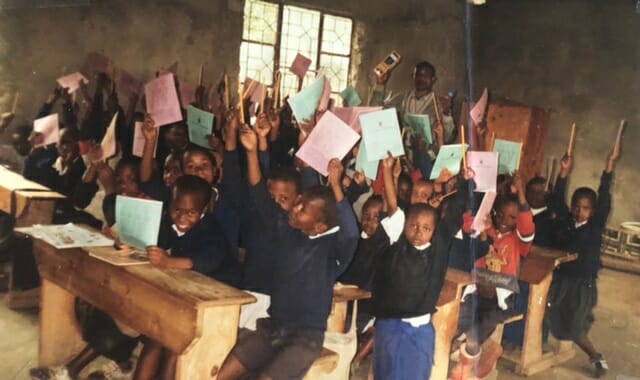

VISIT CLASSROOMS

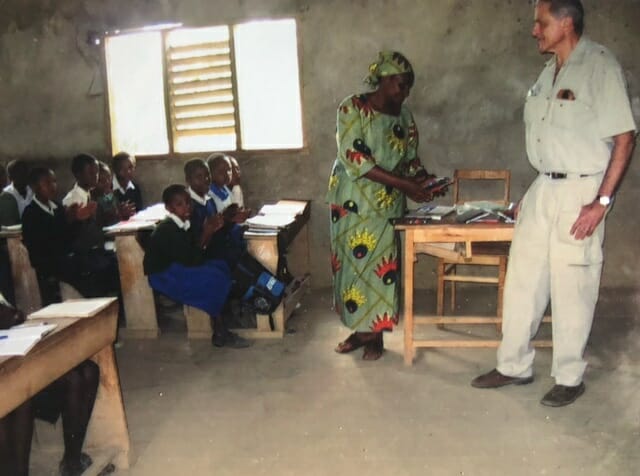

When the interviews end, I ask to visit the oldest class—say, sixth grade. Headmasters always say yes. If the kids have (tiny) chairs or (rickety) benches, I try desperately to sit on one. If they sit on the floor, so do I. The teacher starts by explaining that I have come to watch. Then—always—she asks the kids to sing to me. I clap, thank, and sing to them. The exchange generates warmth between us, and I find my seat amidst a forest of smiles.

After watching a class I can be asked to guest-teach. The teacher and I start by standing together for introductions. Then, the teacher grants me some of her time for a lesson. That maintains her status as boss. During that lesson, her presence guarantees classroom discipline. By prearrangement, she pounces on those of my words the kids don’t understand, and translates. That makes an exciting lesson. It also makes us friends.

As I teach, I invariably see problems. In one classroom, six pupils roasted all afternoon in blazing sunshine—due to a gash in the school roof. They might have learned more if moved into shade. Yet, no one noticed. Sometimes, only an outsider can see. Sometimes, everyone notices, but nobody acts. This school, for example, rationed water—so many cups per kid per day. My reaction: to hire the owner of a donkey to bring water in its saddle bags each morning. Sometimes, only an outsider can see.

I stay in a school until I learn what they lack. I always start with the highest grade—who face competitive national exams. These are life-and-death competitions; high scorers go into high schools. Low scorers must seek jobs in towns where there are none. These kids are desperate to learn.

In consequence, my questions to teachers grow detailed: “Which subject is hardest? (always Math). Which math book do you need? How many? Can three pupils hold one math book while you teach? How much will each book cost?”

FIND A BOOK SHOP

In an ideal world, my driver and I leave a school, drive through the bush to a town, then find a book shop. There, I buy school supplies, pay with credit cards, and drive them back to school the next morning.

Sadly, Africa is not an ideal world. Paths between a school and town can be land-rover-killing deep sand, or black cotton mud. Book store owners who do not know me may insist on cash or make me establish a bank account. School supplies may be unavailable, requiring an order from the nearest city. City orders can be lost, delayed, or ignored.

My notes in hand, I enter the bookstore and order. The store then orders from publishers. Delivery takes longer than I can stay overseas. Thus, I ask bookstore owners to contact each school to say their books are in. The books will then sit in piles on the floor, until fetched.

A headmaster must thus travel to the bookstore, fetch the supplies, then carry them back to school. This is never easy. Most lack cars or scooters. Most do have bikes, but the sand, mud, etc. make biking hard. One school I adopted lies high on Mt. Kenya. The bookstore lies at its foot. It is easy for the headmaster to bike downhill to fetch the school supplies, but hard to climb back up while carrying them–and impossible in the rains—which can delay book-arrivals for weeks.

WELCOME HOME! WANT TO GO BACK?

Once at home, email both the headmaster and bookstore owner instantly. You must reassure them that you are in the game to stay. Africans stereotype Americans as ‘go-away birds’–who “stopabit, takeapicha, (photo) giveapesa (money), flyaway.” Why not eliminate that stereotype in the minds of both men.?

Want to go back? You now have enough expertise to invite someone to join you. Mother-daughter or father-son pairs can have a wonderful experience, both in school and with each other. I took my eight-year-old son to a school on Mt. Kenya. We were instantly surrounded by 300 pupils, none of whom had ever seen a white boy. “What do I do?” he asked. “Shake hands with every one of them,” I said. They loved it. He loved it. (I loved it.)

Bring friends. They share the costs. Some get so caught up in being angels that they go on Facebook or blog home, thus generating more funds for more school supplies. The father and son I once took to Tanzania sent daily pictures of the schools we saw to co-workers and school-mates. They meant only to share holiday news, but coworker and parent donations flowed in.

Could an American school adopt a rural African sister school? Could an American church adopt a rural African daughter school? One U.S. pastor told me he had visited an exceptionally poor primary school in Ghana. He loved it and they loved him. He returned the next year with two church members and their two kids. This time he knew how to help. When he visited the third year, this time with more parishioners, the pupils knew when he was coming and welcomed the Americans with drums. Couldn’t this type of visit become a small but increasingly beloved church tradition, where members go each year, bringing their children to help other children?

CAN WE ACTUALLY MAKE A DIFFERENCE?

Many people who return from Africa put it aside. To ensure that I don’t, I keep the emails flowing as an occasional pleasure, bringing back memories of good times and good friends. Gradually, I mean to saturate the oldest grades with books, slowly supplying one subject after another. When that happens, I’ll start on the next oldest—until I one day reach kindergarten.

I can also get long-term benefits from what I do. Consider this letter. It came from a boy just entering high school. As a ten-year-old, he sat in the front row of a class I taught in an isolated, semi-starving, badly run bush school. The headmaster was drunk. The teachers rarely taught. The pupils were hot, hungry, thirsty and bored.

I guest-taught a class. He asked all the questions. On a whim, I asked if he was an orphan. He was not; his family herded cattle. I then asked, again on impulse, if he would quit this school and transfer (with my help) to a better one. If he did, would his clan split the school fees with me? He did and they did—selling cattle to pay. He went on for years, struggling with boarding school-loneliness, poor study skills and a weakness in English. Yet, on entering high school, he wrote me this:

“Baba (father) I am fine with much happiness and thanks to God for giving me a loving and caring father who never disappoint his children in educational and life matters. The educational journey that I went was too long but I felt short as you stretched your hand for help. The achievement that I’ve made (entering high school) is built around your courageous and kindness heart with much advice and I am praying that God may give you long life.”

Today, this young man is a dentist! Can one not argue that letters like this are rewards in themselves? Africa’s Children do need Guardian Angels. Now! Want to adopt a school?