Reconstructing Black Africa’s Golden Past

By Professor Jeff Fadiman

PART I

Sixty years ago, when I was in high school, I picked up a textbook on World History. It had chapters on every world region but Africa. When I asked the teacher why, he said that Africa had no history. That made no sense, but he was a teacher, and I was a kid, so I accepted it.

When I reached college, I took a course on World History. It dealt with every world region but Africa. When I asked why, the professor said that Africa had no history. This time, I thought he was racist. It still made no sense, but I decided to try to learn more about it.

When I reached graduate school, I met professors who believed that Africa did have a history, but that very little of it was written down. Instead, it existed in the minds of millions of Africa’s oldest men and women, grand-parents who had learned it from their grand-parents who had learned it from theirs.

The problem was that these elderly people were dying, in their millions, all over Africa. Each time a grandfather died, the history that he knew was lost to the world. Somehow, someone had to find them to learn what they had never had a chance to teach. So, I became an “elder-finder.” I left for Africa, not to see lions, but to look for old men.

One day, I entered the Meru region of Mt. Kenya. I was dreadfully nervous. There were thousands of old men. How was I supposed to know which elders knew Meru history? How was I supposed to know how old you had to be to have learned the past? How was I supposed to know who to ask?

I am embarrassed to say that I chose the first “elder” I met simply because he had white hair. To my surprise, he knew a lot about the history of his own clan, and a little about the Meru tribe. I asked hm how he learned it. He replied that he was taught by his father. I met his father. He was taught by a still older uncle. I met the uncle. He sent me to a still older elder. And, so it went. Eventually, I was talking to the oldest living members of the Meru tribe. I had a start.

Then, I decided to get organized. I hired an “outside man” and an “inside man.” The first job of the “outside man” was to discover the oldest and wisest men in the entire tribe. His next job was to walk me to wherever they lived—and every one of them lived in the forest, either far up or far down the mountain and away from any road. I hiked up and down for months. His final job was to sit with me for hours, translating for me as I spoke with elder after elder.

Since every word we spoke went into a recorder, the “inside man” would spend weeks slowly translating the elders’ often rambling tales into logical English. Their stories—to my amazement—ran for hours. Their final messages, however, were always the same.

- Before the British came, our grandchildren were taught to visit us each evening to learn our Meru past. They would come, bring gifts of tobacco, sit at our fires and listen to our history.

- When the British came, they told us that we had no history. Since we did not write, nothing could be remembered. Thus, nothing worth remembering had ever happened.

- Since the British did write they did have history. Henceforth, our children would learn only theirs.

- Then, the British lured our children into schools by feeding them sugar. They were never allowed to leave.

- Now, our grandchildren no longer come to us to learn. The British have taught them that wisdom is only in books, and books are only in schools.

- Muchunku! YOU write books. Now write (my) wisdom in them. Then give your books to (my) children and grandchildren yet unborn, so they will always know what it was to be truly Meru.

The Origin Traditions

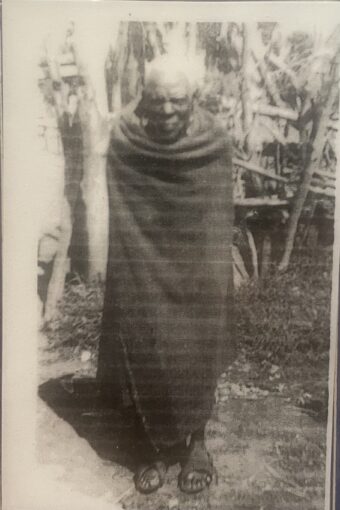

Over time, I visited scores of elders. They taught me hundreds of traditions, each one reflecting a priceless bit of tribal history. One man, however, stood out: Gituuru wa Gikamata. He was believed to be the oldest man in Meru, perhaps near 100. He could recount vast numbers of the most ancient traditions, those which went back to the beginnings of the tribe. Here is the first, the “origin tradition,” told in his words:

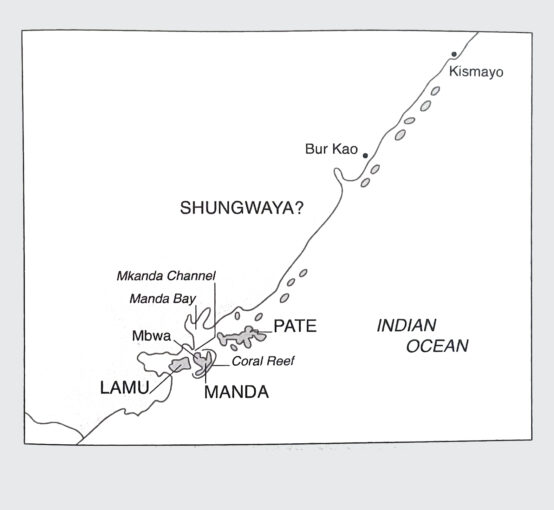

“In the beginning, we were not called Meru. None of us remember our tribal name. We do know that we once called ourselves Ngaa. None of us now knows what that means. We also know that we began on an island. We called it Mbwa.

Mbwa was small. You could walk across it in half a day. The soil was mostly sand and black rock (coral). However, there were springs of sweet water and bits of good earth where we could both grow millet and yams and keep goats. We also gathered coconuts and bananas.

However, our main food was fish. Every boy had a long, thin, sharpened fish stick. We would wait, watch, throw, pin a fish, and leap on it. Then, we would eat.

But the Surrounding Water Was Evil

Mbwa was surrounded by bitter (salty) water that no one could drink. This water was alive. It hated people. Each day, it would gather itself, hiss, foam, then run away to the shore of a Big Land (the African mainland). There, the water would eat grass each day. Suddenly, it would race back along the same path, angry, hissing, and glad to seize and eat any person it could catch along its route.

We understood the water hated us and watched it constantly. Thus, we were able to live happy lives alone on the island. We worked constantly to find and grow food, but there was always enough. We knew people on the Big Land with whom we could eat, drink or trade. However, they all looked like us, ate with us, and spoke our words. (language) None were enemies.

The Enslavement Traditions:

One day (around 1700), a white sail ship appeared, landed, and spit out invaders. We called them Nguo Ntune (red clothes), since they wrapped red cloth around their bodies. Their skin was brown, their hair was black and straight. They had cold, black eyes, long noses and thin, cruel lips that never smiled. Each man carried an iron-tip spear and an iron sword, the blade of which curved backwards.

Our young men were ready to fight them, but the elders stopped it. Having had no enemies, we had no weapons. How do you fight swords with sharpened fish sticks? We surrendered. They enslaved us. Our goats became their goats. Our millet became theirs. Our boys were forced to fish for them. Our women gathered fruits for them. They ate well.

However, we made bad slaves. We thought up many clever ways to anger them. Finally, truly angry, they gathered all our men together and set us the first of five terrible tasks. Each time we failed one Ngaa would die.

The Terrible Tasks

The first task was to drop a single round fruit into a deep well, then retrieve it without using either hands or sticks. Baffled at first, our elders appealed to the Mugwe, the elder closest to our Nkoma (ancestral sprits). He called on them. They advised him. We filled the well with water and the fruit floated to the top, untouched by hands or sticks. The enslavers were not pleased.

Their second task was for our elders to present the conquerors with an eight-sided cloth. Again, we turned to our Mugwe. Again, the Nkoma advised him. Our elders presented the invaders with a corn husk, freshly peeled from its corn. It had eight sides. Again, the Red Clothes were not pleased.

A third task was to make a sandal from animal skin, but with fur on both sides. This time, the Mugwe did not even speak. He rose, cut the dewlap from his cow, carved it into a sandal, then gave it to the elders with the fur of his cow on both sides. They passed it to the conquerors without a word. This time, their silence was laced with rising anger.

The fourth time, they jeeringly ordered the elders to provide them a dog with horns. The Mugwe caught his dog, tied it to the ground, then cut two small open wounds in the skin above its skull. As they bled, the horns of a newly caught dik dik (tiny antelope) were placed in each wound, then smeared with tree sap. Blood and sap mixed to form a hard paste. The dog was then presented to the Red Clothes in intensely hostile silence.

The enslavers, now deeply angry, commanded the Ngaa to perform a task both sides knew was impossible: To forge a spear so long that it would touch the clouds. This time the Mgwe responded with profound sadness, for the Nkoma had come in the night to inform him of his people’s future and it seemed terrible. To survive, the Ngaa must flee the island and wander he knew not where.

He instructed the elders to tell their tormentors that the Ngaa would construct the largest forge ever built, one which sent flames up to the sky. The Nguo Ntune were warned to move to the island’s far side, lest the ancestral power contained within the flames consume them. Startled, they complied.

When night fell, the Ngaa simultaneously burned every one of their homes, setting a huge fire and thus a great glow in the sky for the invaders to watch. Then, Mugwe told them to gather what they could carry and flee Mbwa to the mainland. Each man was to carry a goat. Each woman took yams. When asked how they were to cross the water, the Mugwe admitted that he did not know.

The Ngaa raced to the island’s edge. The channel between Mwba and the Big Land was so deeply under water that no one dared cross. Mugwe scattered powder on the waters, then struck them with a stick.

The flow raced away (whether through tidal action, the will of Nkoma or the Mugwe’s magic is unstated). Every Ngaa fled across the ocean floor, picking their way over the sharp coral to the mainland. The water was up to their ribs. Each man held his goat to his chest, lest it drop and be drowned. Before dawn, the waters swiftly returned. The Nguo Ntune dared not cross. We walked. We walked. We walked for 30 years.”

I spent fifteen months among the Meru, interviewing more than 100 of the oldest men and women over 300 times. I collected 100’s of “traditions,” many as interesting and beautiful as this. Some tell of the way that Meru waged war, in such a civilized manner that the British could not comprehend it. The very idea of “civilized” war was beyond the scope of their imaginations. Consequently, they destroyed the entire military system.

Other traditions tell of what the British miscalled “African Witchcraft.’’ The Meru used verbal curses, but in ways that were not evil but a complex and sophisticated system used to maintain communal harmony. Again, because the methods used were beyond the British capacity to comprehend, they destroyed the entire system. Then, having destroyed huge portions of the tribal past, they told the Meru that they had never had a history.

They were wrong! African history is not ‘dead.” It will never die, as long as it lives in the minds of Africans and those descended from Africa.

In the next issue of “The African,” I will tell you how this small African tribe waged “civilized” war. In the issue thereafter, I will describe how they used supernatural “curses” to maintain social peace. Ideas like these should live forever.