Fight on for Zulu U!!

Shouldn’t African education be African?

By Professor Jeffrey Fadiman

And there I stood, before a classroom over-filled with 150 smiling students, in the University of Zululand (Unizul). The room was jammed. Students filled every chair, space on the floor, window, doorway and into the hall. They had come to see Unizul’s first and only American Professor (me) give his initial University lecture. Roll call was not only impossible but against Unizul rules. On arrival, I had been told that students had gone on strike against it, and won. The room was hot, hot, hot, both from the sun and the sheer number of bodies which had squeezed in.

I lectured. Dead silence. Everyone listened, eyes on my face. I was surprised at their intensity. What I was saying was good, but not riveting. Then, I stopped the show to say that the first examination would be in four weeks. The room went still. Nobody breathed. Then six students called out at once, each with the same question: “Nkosi (Sir), can we share the exam answers as we write them?”

I laughed, thinking they were teasing, and answered “No! Wouldn’t that be cheating?” The same reply now came from all over the class. “Nkosi, that rule is cruel. Here, we are all brothers and sisters. We want everyone to pass, not some pass and some fail. You want everyone to pass. Why should we not all help each other?”

I overruled the protests, eventually giving the exam to a room filled with universal resentment. Notwithstanding, the little voice that lives inside my mind now asked incessantly: “What if they’re right? I do want them all to pass. Why shouldn’t they help each other”?

SAWUBONA, KWAZULU (I see you, Zululand)

Unizul is in Zululand, which is in South Africa. Zululand is beautiful beyond any songs that can be sung of it. Even the ocean, just behind a line of hissing waves, is alive with the fins of sharks. My home lay near a Great White Shark breeding zone, thus making each attempt at surfing a life or death adventure.

Inland from the shark fins lies 300 miles of sun-scorched beach. Behind the beach; 300 miles of bright green sugar cane. The cane cloaks hundreds of tiny rounded hills in an undulating carpet of green that rises and dips as I drive to Unizul and overcrowded classrooms. The hills are broken by lazy, red rivers, fed by rains that never seem to stop. Zulu rivers have Zulu names that sing in my mind as I drive: “Mzimtimkulu, Thukela, UmfolozI.” Once they hid hippos. Some still have crocs. Each time I look, I hope to see ice-cold eyes.

At harvest time, the Zulu burn the sugar, firing fields to singe the seven-foot stalks before cutting. The cane crackles and the crispy smell of burning sugar fills my nose. Sugar-smoke fills the sky and covers the sun. The sun strikes back, turning it into crispy mist. The mist boils up into pinky clouds, which turn back into the warm sugar-soaked rain that tumbles down onto everything I do.

Inland, behind the sugar belt lies what the Zulu call the “Valley of 1000 Hills,” mile after mile of smallish, roundish, greenish hillocks, where sweet-grass slopes silently invite me to walk on them, while rank, tangled sour-grass valleys signal me to stay away. There are no slums. Zulu huts are neat and spaced apart. The earth is filled with pumpkins and beans, sheep and goats, kids and fattish women swinging hoes.

MORNING IN ZULULAND

On lecture days, I jerk awake to the screaming of birds and roosters, all of which go mad the moment they see sun. I bravely stride into the kitchen, only to be driven backwards by a million army ants, trooping in a long, dense, narrow column from a window into the stove.

Jumping over the ant-army, I eat, go out and unlock the 11 locks on my car. Bravely, I check that no thieves have sneaked under the car, behind it, into the back seat, the trunk or adjacent bushes.

Reassured, I drive uphill towards the main road, passing a few Zulu women, chatting, sitting on the ground and waiting for a lazy bus to take them uphill to a tea shop. Some of these women are heavy, and find it hard to walk uphill in the hot Zulu sun. I wave them all into the car. Thrilled, they try every English phrase they know; I try every Zulu phrase I know—and all we ride up the hill laughing ourselves silly.

I reach Unizul in 20 minutes, enthralled by the red earth, green sugarcane and blue sky. I park, lock my 11 locks and hike uphill to my classroom. I pass my students, sitting in small clumps under shade trees. I call out “Class starts in six minutes. Come climb with me.”

“Classroom is hot, they call back. Here is shade. You come here, sit with us and teach?” They are right; I should teach on the ground, in the shade. Instead, I grimly climb, reaching the classroom just on time. Then I stand there, every day, hot, punctual and all alone.

SWIMMING UPSTREAM TO SEEK KNOWLEDGE:

The students do come eventually, drifting into class in chatting groups over the next two hours, blissfully unconscious of being late. Unizul education baffles me. Gradually, I become a useful cog in the system, knowing what goes on, but never why.

Students flood my classes. I teach; They listen. No one takes notes. No questions; but they listen—oh how they listen. They want to learn. Toss them into water and everyone will swim. However, Unizul swimmers must paddle upstream, fighting fierce educational counter-currents, each of which impedes what they learn.

An educational counter-current is a belief that denigrates the quest for education. Consider the special names, for example, that U.S. kids soon learn to apply to other children that are too smart: egg head, nerd, geek, spaz, wierdo, and (in adulthood) wonk. Consequently, most of us receive conflicting messages as we mature: Go to school, cooperate but pretend not to like it, praise a teacher but never your education, never say you want to learn, don’t ask too many questions and for God’s sake, don’t act smart.

Zulu students, however, must swim against counter-currents far stronger than peer-group mockery. One is the need to cope with education that is wholly British. Although Unizul is physically in Africa, the education it provides is born in London: British-style lectures and exams, required attendance, fixed deadlines, fear of failing. Virtually nothing in the University (except the food) reflects their African heritage. For some, that means swimming upstream.

Beyond “going British”, many students struggle, subconsciously, against a non-stop flow of covert messages, many absorbed since childhood. Some are passed down by ancestral tradition. Others come from fathers who fought for decades to liberate their land from Whites.

A few come from political leaders who have promised students things they now resent. Some spring from student desire to assert authority against the older generation.

Ancestors? Fathers? Politicians? Peers? In those mouths, the messages ring with authority, endowing anti-learning with respectability and power. They work sub-consciously, pushing against the desire to acquire education.

ZULU TRADITION: RESPECT FOR ELDERS

One source of these counter-currents is African tradition. Zulu tradition once required the young to learn wisdom from their elders. At night, elders would sit near the fires, surrounded by circles of grandsons.Tradition also required the young to sit in silence, their eyes on the face of the elder who spoke. No narration began or ended at set times. Youngsters simply appeared and left. Nor did the young ask questions. Their task was to learn wisdom by listening—and memorizing.

In modern Unizul, this profoundly respected tradition acts as a countercurrent, obstructing student learning. No class attendance is taken, lest students object. Instead, they drift in and out, obeying tradition. Sometimes, I began class in an empty room. They came eventually, then treated me like a Zulu elder–sitting, eyes on my face, listening. No notes. No questions. They learned my wisdom by listening—and memorizing for exams. The result, of course is that less learning occurs.

LIBERATION BEFORE EDUCATION

A second counter-current can be traced to South Africa’s Liberation Struggle. Under Apartheid, ruling Whites tried to force all African students to study only in Afrikaans—the language of South Africa’s Dutch-descended Afrikaners. Students revolted. Trashing the schools, they coined the slogan “Liberation Before Education,” then abandoned schools for years, to take up the liberation struggle.

They fought the Whites with slings and rocks, using garbage can lids as shields. Then, one day, they won. The Whites transferred power to Mandela, who called for a Rainbow Nation, where everyone of every color could live in peace.

For ex-schoolers, however, nothing changed. Thousands moved to the cities to seek jobs, finding nothing. No schooling meant no skills which meant no work. Years passed and nothing changed, while many African leaders called for the anti-White struggle to continue.

As one African scholar told me: “It was this period (of the Liberation Struggle and the empty years beyond) that set off mistrust . . .and disrespect between African youth and parents. It was then that most parents were disrespected by the youth because (they) were said to be spies and White-fearing. This was also so in the schools, where toyi-toying (protest dancing) was brought from the streets into the classrooms and where teachers lost (student) respect . . .in the name of liberation.”

Years later, Unizul students, whose fathers fought the Whites, still hear the echoes from this era in their minds. Whites are still around, in positions of authority. Why? Many Unizul teachers are White. Why? If teachers—and other Whites—draw no respect, why come to their classes on time? To attend classes promptly displays respect. To come late or not at all displays the disrespect they feel is due. Absence is protest.

One student I knew always came to class just six minutes late. When asked why, he said: “I don’t like White teachers, but must always obey them. I want to hurt their feelings, but only a little, so I always come just six minutes late so they get angry, but never punish.”

Since no student must appear, some never do. They enroll, pay fees that let them attend, then “float” quietly among the classes, learning (they argue) whatever they hear. Tradition permits it, but also limits learning.

Floaters also dodge assignments. Since I could never take attendance, I could rarely give assignments. Nor could I learn who wrote them without attending lectures. In one class, I gave an essay to 130 students. I got 40 back, but most were identical. In a sharing society (my class), brothers and sisters simply helped one another. That was not cheating—just tradition–an historical countercurrent that inhibits student growth. Four ways to express latent anti-White resentment: Cut class, come late, copy exams, ignore deadlines. Seems harmless. Who is hurt? But, what of their education? Could a more African tradition be used to lower this resentment?

MASSIFICATION:

During and after the liberation struggle some African politicians created a political counter-current, by demanding that university education be “massified,. . .away from the present elitist and skewed base where the majority of Whites and a minority of Blacks are catered for. . .drawing more people into higher education by doing away with the existing requirements.” (Mail and Guardian, 4/19-25, 1996)

In Unzul, this meant opening classes to virtually every secondary school graduate, a policy which then expanded informally to include ever larger numbers of former graduates. The method was simple. Anyone could attend lectures. One student told me that he had “floated” for three semesters, drifting among classes without paying. No one ever checked that he attended, took exams, wrote essays—or even paid fees.

Class sizes exploded. My first class—I was told—was over 150. My other classes were similar. My small department, composed of four faculty, had (I was told) 689 students, with more arriving daily. One student appeared 13 weeks after my classes began, declaring that she had just registered, then politely demanding credit for the entire semester.

Nor could I count the masses in my classes. Leaving aside student opposition to roll call, common sense forbade calling out 120-150 student names, particularly when many Zulu had identical names. Giving assignments to the masses also posed problems. Fellow teachers, driven frantic by the numbers, often tested only at semesters end. As mentioned, I assigned essays four weeks into my teaching, rumbling pointlessly about a one week deadline. It came. No essays appeared.

Over several weeks, some essays did trickle in, neatly written and often on topic. As mentioned, many were identical. Other writers, clearly, had never attended class. One, which I treasure, ignored my question completely, instead providing all the reasons she was NOT qualified to go to the USA on scholarship. What grade, however, should I have given to the tens of students—who had ignored me completely but were still in class?

Massification was well-meant. We applaud extending elitist education to the masses. In Unizul, however, it is just another counter-current; it creates floaters. I have talked to many floaters. They come, then float for semesters, drifting from class to class seeking teachers they like. When they find some, they listen. One could argue that they are “exposed” to academic knowledge. However, exposure does not mean absorption. One could also argue that little education is taking place. Could a better system—an African system—be devised?

Eventually, floaters and listeners alike face exams, often having failed to develop the study-skills to survive them. Some merely memorize and then repeat the lectures they have heard—regardless of the question asked. Others use a Unizul-wide technique of avoiding exams altogether. Instead, they approach a professor and politely “demand” a “task” (USA: “make-up”), equivalent to the many lectures they have missed.

In my world, this would mean assigning a multi-page research paper, complete with footnotes and well-grounded opinions. To my students it meant being given a chance to copy from a library book. My refusing to provide a copyimg task always provoked the most courteous resentment, along with oh-so-carefully coded remarks that I was (almost) as “racial” (USA: racist) as the other White professors. Taskification, in fact, is just a desperate student strategy to replace British-style written exams with copying, thus lowering both student stress and learning. Could we not resolve the problem with something more African?

STUDENT TRADITION: STUDENT STRIKES.

Unizul students have also developed their own tradition: the student strike. I have been told these began with good intentions. Students across the University once objected to the food in Unizul eating halls. They went on strike and it improved.

However, initial success led to excesses and strikes became near-weekly events. One strike took place when a group objected to their female members dating males in another group.

Another occurred when one segment objected to other students cutting choice paragraphs out of library books to copy papers, storming the library to protect its contents.

The most notable event, however, was what I call “The “Great Midterm Strike.” Students across campus had grown dispirited by the high rate of failures (40-60%) after every exam. Organizing, they demanded the faculty “lower the bar”, so that a greater percentage could pass, threatening a campus-wide strike if refused.

To my amazement, the professors discussed the “demand” at length. Eventually, the Academic Senate agreed to “lower the bar.” Henceforth, midterm grades would count, only if higher than the final exam grade. In short, the students rode another counter-current which “lowered the bar” on their own education.

ARE AFRICAN IDEAS WORTH TRYING?

Many African educators have called for eliminating European methods of education, including required attendance, competitive exams, grading and even individual accountability. They want them replaced by African educational methods, which they argue have worked for generations. Reconsider, for example, the request students called for in my first university class: “We are all brothers and sisters. We want everyone to pass. You want everyone to pass. Why can’t we share the answers?”

Why not indeed? Why couldn’t African Universities offer education to groups instead of individuals—in fact, offer it to members of existing clans? Couldn’t clan members share the (often scarce) existing books, pool lecture data, prepare collectively for tests, share possible answers, and pass or fail as family units? If competition is required, why not have the clans compete, either for status or symbolic awards? If a clan fails an exam, why not let them retake it—or collectively relearn that course segment on which the exam was based? Yes, everybody would pass, but isn’t that the point?

There are advantages. Weaker students might be pushed along, both by peer pressure and personal assistance from stronger comrades. Stronger students might help the weak, to maintain clan honor—surely a better educational outcome than one in which the strong compete with the weak and crush their educational aspirations.

Group-testing might also modify competitive grading, replacing it with a system in which entire clans receive a “pass”, “pass-plus” or “excellent,” based on their ranking against other clans. The goal would not be to pass, but to excel.

This system might also eliminate massification. Rather than opening all lectures to virtually all post-secondary gaduates, existing clan-elders could decide which students might enter university, obeying limits set by Government. Once selected, elders might form them into an academic impi (traditional Zulu military unit), charged to bring honor to the clan through their unified academic performance..

A more African system might also resolve the problem faced by students who can only learn through listening. Once allowed to “share the answers,” clan-groups might follow tradition one step further, transforming entire lectures into chants, to be learned collectively until everyone knows everything and is ready to be tested.

Finally, Africanizing education might soften the racial resentment students may still carry from the years of liberation struggle. White educators would still be in classrooms. However, they would be teaching within an African educational system, derived from indigenous traditions instead of Western. Would students not feel satisfaction to see a European academic system replaced with their own?

One final fact does make these ideas worth considering: They are African. Africa is still communal—composed entirely of sharing-societies. It is neither individualistic, nor competitive. Why should African students, therefore, be forced to instantly abandon every communal ideal, in favor of unending competition, the moment they enter an African school?

Many Whites instantly and automatically dismiss African educational ideas as inferior to their own. They have difficulty considering or even imagining the ideal of a sharing-civilization, having absorbed the alleged “superiority” of individual competitiveness since birth. Thus, societies that share are believed inferior by definition. In consequence, African educational concepts are never tried in Africa. Shouldn’t they be?

__________

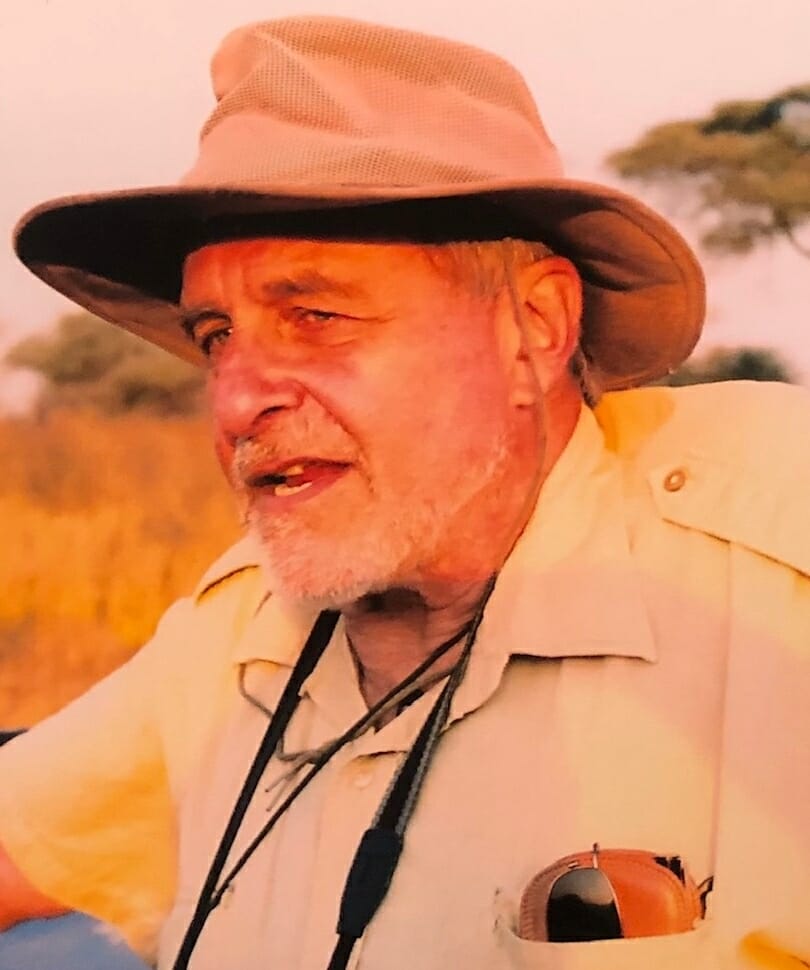

Jeffrey A. Fadiman, 85, is a professor of Global Marketing at San Jose State University in California, and a Language and Area Specialist for Eastern and Southern Africa. A graduate of Stanford University with two years at the Universities of Vienna and Free Berlin, this Fulbright scholar taught both U.S. and global marketing tactics at South Africa’s University of Zululand. He first experienced Africa in 1960 by canoeing up the Niger River to Timbuktu. Thereafter, he lived in Meru, Kenya, where he rediscovered the traditional history of the Meru tribe, which had been crushed by British Colonialism. Fifty years later, the Meru accepted him as the first White Elder of their nation. Professor Fadiman has supported both Tanzanian AIDS orphans and the schools to which he sent books, pens, paper, and hope.