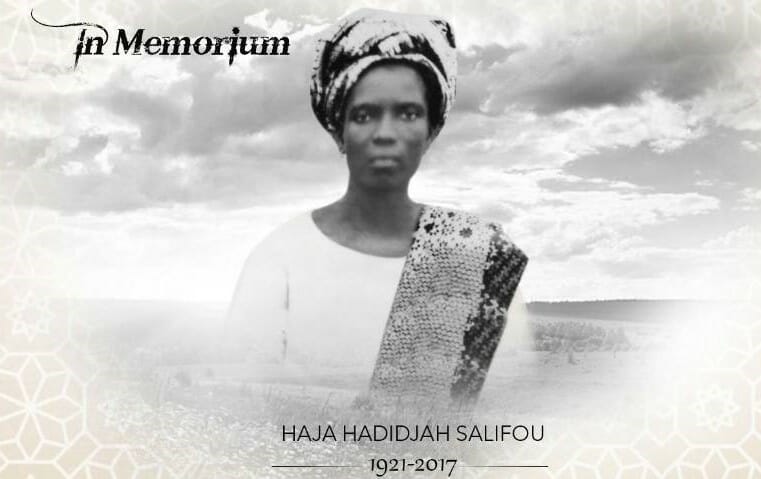

Celebrating Black Women: Hadeejah Salifou

BY LOU SIFA

For her six children, family members and others who are familiar with her life story, Hadeejah Salifou deserved a Ph.D. in parenting and the ability to survive the odds. But the reality is that this woman from a remote village in Benin who was able to send two of her sons to some of the finest universities in the United States and Europe, and whose grand-children—including a Ph.D. holder—are pursuing great careers in Fortune 500 companies in Europe, the United States and across Africa, could not read or write.

Hadeejah Salifou was born circa 1921 in a remote village called Colli-Védjigon, 75 kilometers (46.6 miles) from Cotonou, the largest city in the West African country that was then known as Dan-homê, wrongly named Dahomey by the French coloniser who didn’t know better. (In the course of the country’s turbulent political history, a military government tortured history in 1975 to rename it Benin, as it is now known.) Salifou was married to an older man, Mama Salifou, a devout Muslim who took her out of the village in the early 1950s to Cotonou. That was nearly a decade before Dahomey became independent from France (some say only on paper) in August 1960.

Growing up barely a quarter-century after France had defeated the powerful kingdom of Dan-homê in 1894 after a protracted war and unified several local kingdoms into a territory that became the Dahomey colony, Hadeejah belonged to the more than 99% of the then-Dahomean population without a formal education who could not write or read in French. But she was determined to save her children from the same handicap, which put her at odds with her Muslim husband who had a different plan.

In the fall of 1956, the couple’s first son had reached the age to be enrolled in what was then called “the white man’s school,” the regular school established by the French colonial administration. But, earlier that same year, Mama Salifou had sent the child far away from home to receive the Islamic education necessary to prepare him to become also a well-rounded Muslim. To the contrary, Hadeejah preferred that her son attend the secular school, the only avenue to acquire a French education conducive to a career in the civil service.

This led to a clash between the couple, a David vs. Goliath sort of confrontation—though a non-violent one. The highly-respected spiritual leader vs. his younger, pragmatic and western-leaning wife who, to anyone’s surprise, resorted to a quiet, yet effective weapon.

A cunning, stubborn Hadeejah started spreading false information alleging that her husband had given their son to a friend of his in exchange for money. In no time, the rumor reached Salifou but did not infuriate him. Rather, the old wise man quietly brought the young boy back home to his mother, not as an act of capitulation, but in a spirit of compromise and peace that are the attributes of a man of God. In no time, Hadeejah made all the administrative arrangements to enroll their son in the so-called white man’s school.

The boy excelled in school, went all the way to college in Benin and overseas, including the prestigious Johns Hopkins University in the United States which ranked 12th overall out of the nation’s thousands of academic institutions. He became the first member of the entire Salifou family to visit the United States, and later settled there upon finishing his studies. He embraced a career in journalism, becoming an award-winning reporter at the Voice of America in Washington, D.C. He crowned his life’s pursuits with the launch of the premier African magazine published in the United States, The African Magazine, which was graced by a 22 May 2002 congratulatory letter from then-President George H.W. Bush.

Hadeejah Salifou’s second son excelled in school as well, attended renowned universities overseas including the University of Leeds in UK, and embraced the teaching career overseas. He later returned to Benin and started a construction company. A long-time Rotarian, in 2011 he rose to the position of governor of the district 9100 of Rotary International which then encompassed 14 West African countries.

In his upcoming memoir, which he is dedicating to his mother, Hadeejah’s oldest son writes: “To my mother: My best friend, my heroin, the roots that have nourished me, and the torch that will always light up my way in this obscure and dangerous world.”

He also writes about the courage and tenacity of his mother, especially after her husband’s death: “Dada was one of the hardest-working and most brave women that have ever existed, working seven days a week, from dawn to dusk. None of the so-called ‘male’s jobs’ was too hard for her: chopping wood, fixing our fences when they were broken, or erecting the bungalow that served as her workshop.” He adds: “Consequently, she never failed one single day of my entire young life to provide me with at least three nutritious, tasty meals, sometimes consisting of food staples that, in those days, were found only on rich people’s dinner tables: chicken, rice, macaroni, eggs, and salad, not to mention more traditional Benin dishes such as vegetable stew, palm-nut stew or okra stew cooked with beef, lamb or smoked fish, crabs and shrimp, and served with a hot, steaming corneal we call wô.”

After the demise of her husband and mentor in 1959, Hadeejah, then 38, remarried. But that did not stop her from working hard. In fact, she worked harder, and her clothing-dying business prospered, which allowed her to meet the higher costs of raising her children and their school expenses. She did so well she was able to buy a plot of land right there in the nation’s largest city.

It was widely believed in the old African society that if a woman challenged her husband as Hadeejah did by spreading negative and false information about Mama Salifou, that backfired. In this particular instance, it would result in the child failing at school. So Mama Salifou sought to prevent that from happening. During his first school break, the oldest son visited his dad in the village. (The old man had then settled back in the village after being enthroned the chief of the overall Salifou family.) One day after the mid-day prayer, the father called the little boy for a talk. “Your mother got pretty restless about sending you to the white man’s school,” the wise old man started, adding: “but a child needs his father’s blessing to succeed in life.” Then, the now-magazine publisher recounts, the old man placed his right hand on the boy’s head and whispered some verses from the Holy Quran and then showered his son with blessings.

The son also writes in his memoir that he views his dad’s blessings as a necessary complement to his mother’s bold move to enroll him in school in the first place. Those blessings, he stresses, are a key factor in his academic and professional successes.

While working in Cote d’Ivoire, Hadeejah’s second son arranged for mom to visit with him there in 1985. Equipped with her brand-new passport, Hadeejah, then 64, landed at the Abidjan airport under a bright, blue sky, and was driven by his son to Gagnoa, in the west-central region, where she spent several months with her son and his family. There, Hadeejah once again demonstrated her ability to beat the odds, large and small. Despite speaking no French or Bété (the main native language in the Gagnoa area) she was able to communicate with the vendors in the market each time she went over to buy the ingredients necessary to make food for her son and his family.

After the life-changing trip that took Hadeejah out of her native village in the early 1950s to settle in then-Dahomey’s largest city, followed by her travel to Cote d’Ivoire in 1985, and her exhilarating pilgrimage to the Muslim Holy Land in 1995, she embarked on the grand trip of no-return on 22 April 2017, after a brief illness, at the age of 96, in the very arms of her oldest son (who happened to visit Benin then) surrounded by his siblings.

The matriarch was mourned by 24 grand-children, some of whom work as researchers, architects, engineers, business managers and consultants in Fortune 500 companies in Washington, D.C. and Miami (U.S.A.), Nice and Montpelier (France), Abidjan (Cote d’Ivoire), and Dakar (Senegal). She was also mourned by her dozen nieces and younger cousins she has raised and who owe her their elevation in life, and their own children. She is survived by 40 great-grand-children.