Why is that elephant charging our car?

BY JEFFREY FADIMAN

IMAGES BY SCOTT HOLLBLAD-FADIMAN AND DAUDI SOLOMON

There were only four giraffes, including the baby. Eighteen feet tall and 400 pounds, they formed a tight line as the leader stepped timidly into the river. It was shallow, about six inches high. But if flowed, and giraffes don’t like that.

The leader stepped onwards. The others followed. One, two, three steps, then stop. He jerked back as though he’d seen a crocodile, turned back, walked along the bank, then stepped in again—and again and again. The sun dropped like a stone, as it always does on the equator, and as the darkness swooped down, I looked back to see them try and fail once again.

Ever dreamed of going on an African safari? What would you do? What would you see? How much would it cost? Would it be worth it?

My son and I tried ten safari days in Tanzania. Our first shock came as we left the plane and entered the airport. Try to imagine an airport in which every single employee welcomes you—in Swahili—to the country. Try to imagine one in which older passengers (like me) are taken out of the inevitable long lines and served first, instead of waiting. Try to imagine one in which women with kids, standing dead tired in the lines, are picked out and guided to chairs. Try to imagine a caring airport! You can’t? Welcome to Tanzania.

We step outside the airport into the “real” Africa. It’s dark. It’s hot. It smells good. It’s very noisy. In the darkness, I see 50 Africans, grouped in a semicircle in front of us, each waving a sign in the air and happily shouting. Terrorists? Taxis? No. Just drivers from 50 safari firms, each waiting to pick up clients. We find ours, then drive off into the darkness.

A Tanzanian People Day

A good African safari includes conversations with African people. We took a whole first day just to talk. Some of the people we met were old friends. As they produced children, I had helped them by sharing the costs of their ever-larger school fees. Now, they not only welcomed us but showered us with gifts.

This surprised me. Over the years, I have also helped people in the U.S. Each had responded only by saying “thank you.” Very few had ever helped me in return. To Americans, “thank you” is a magic word which excuses us from repaying our benefactors—with gifts, services or favors of our own. Simply put, if someone helps us, we say “thank you” instead of helping him or her in turn.

Africans march to different drums. When helped, they help back, often waiting years to repay an act of kindness with one of their own. These people had waited years for me to return to Africa. They showered my son and I with gifts—small gifts (a kilo of coffee, a pair of sandals, etc.), but each given from the heart.

We ate (roasted goat) and talked for hours about the same things people talk of anywhere: how good our kids are, how bad the schools are, what “Serikali” (government) should do but doesn’t. They also taught my son Swahili, beginning with “hello” “please” and “thank you,” but ending (40-50 memorized phrases later) with entire proverbs: “Poa kichizi, kama ndizi, kwenye friji (English: I am as cool as crazy bananas in the fridge). Good language progress for one day in Africa.

Elephant Day

We entered a wilderness reserve that was famed for its elephants. In dry season, it has only one river, which is the only source of water. 2,500 elephants swarm all over it, drinking, washing, wading and even swimming—trunks held just above the surface. However, we came in wet season. Every inch of the park was drowned in daily rains. The elephants, in their hundreds, had moved entirely out of the reserve onto an adjoining mountain, to breed. The entire place was empty.

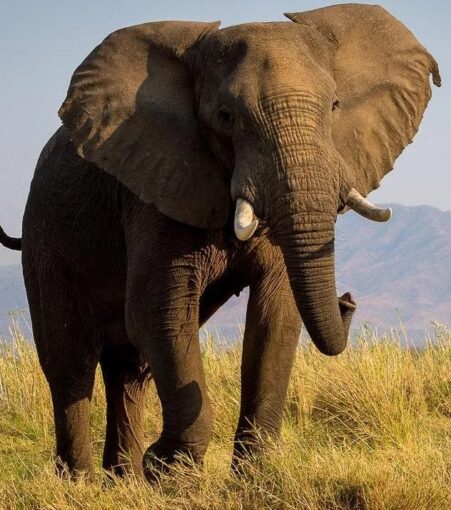

There was one exception. We drove and drove, seeing absolutely nothing except the constant flashing of three-colored birds, at the rate of one bird on the highest branch of each tree. Then, a huge grey blob blocked our only path—a single, bull elephant, quietly grazing, no doubt the only one left out of the 2,500 we had come to see.

We stopped the land cruiser to watch and admire. He stopped too, whirled, and charged! He moved slowly at first, but picked up speed, trunk up, ears out and tusks pointed clearly at me. Our driver jerked the land cruiser off the path and into the bush, making a tight turn to get back on the road, facing away from the charge.

Briefly, I realized that it was a risky maneuver. If a tire hit a hidden aardvrark (ant bear) hole, it would stick, we would stop, and the elephant would win. However, we won. We regained the road, facing away from the charge and raced away.

Maasai Market Day

A good safari never passes by a local market. The Maasai were once famed as spear-carrying, cattle-raiding lion killers. To reach manhood (and thus access to a woman), each Maasai had to single- handedly kill a lion with his spear. Today, they heard goats, sheep, cows, and donkeys, leaving the lions in peace.

Each Wednesday, they cluster in open-air markets to buy, sell, and gossip. As we appear, a single, long row of women sit side by side, each with identical stalks of bananas to sell. Multiple men stand stock still—each surrounded by goats and loudly soliciting customers. Everybody talks at the top of their lungs. It sounds happy.

More important, everybody smiles and greets as my son and I appear. These are villagers. They do not get much chance to look at Californians up-close. They joke, tease, hold our hands and beg us to buy their goats and bananas at ten times normal prices.

We bargain for things we don’t really need, thus become part of the day’s entertainment. These sellers don’t have much to do but talk. They sit or stand for hours. If a foreign customer appears, stops, fails to greet, asks a price, and then buys without bargaining, he disappoints everyone withing speaking range. What they hope is that he will stay, greet everyone within voice range, exchange names, bargain forever and thus entertain. Each time we make them laugh, the sky-high price comes down.

The entertainment begins, for example, when the women point to my white hair, asking if I am the baba (father) or babu (grandfather) of my 6’2” son. I touch my hair and say: “Here, I am mzee (old).” I point to my groin and say: “Here, I am kijana (young).” Then I point to my son as proof. An explosion of female laughter follows and the sky-high price comes sharply down.

Into the Volcano Day

Ngorongoro (In Maasai language, the word suggests the clack-clacking of a wooden cowbell) is the largest caldera on Earth. A caldera is a pot-like depression in the ground. It is caused when a volcano erupts and then collapses in on itself. This caldera is the only complete example on Earth. The rim is ten miles across. The floor is home to 115 animal species (30,000 animals) and 550 types of birds. Once you drive across the grassy floor, you will never be alone, but always surrounded by wildlife.

To get into the caldera, your vehicle must go up through what looks like a fictional jungle and then down a slope so steep that it looks like an accident waiting to happen. Once down you drift peacefully through the herds for an entire day.

Ngorongoro’s lion population is one of the densest in Africa. However, my favorite animal is the rare peanut butter monkey. He lives in a tree, just above a toilet on the edge of a picnic ground. He has declared war against humanity and dedicated his life to stealing their sandwiches. He has stolen my sandwich each time I have visited the Crater. When other innocent tourists settle down for a picnic, they spread out their food. Instantly, the monkey flashes down-tree, swoops on the table, hisses at them and steals. This time, he took my carefully horded stash of peanut butter.

Wildebeest Migration Day

Serengeti’s 2,3000,000 wildebeest are constantly on the move. Joined by 35,000 zebras, thousands of gazelle, hundreds of eland and a surrounding ring of lion, leopard, and hyena. They march—in a column 40 km long—on a non-stop, life-long 8,000 km trek around and around the Serengeti.

The migration starts with the birth of half a million calves in a few weeks. The births coincide with the rains, which thunder down on the unending grasses turning them green. The herds follow the rain clouds, trekking from South to West to North to East and back again forever. No better illustration of the circle of life exists.

However, there are rivers to cross. The largest holds 3,000 crocodiles. The migration leaders reach the river, balk, try to turn back and—eventually—get pushed into crossing. The followers cross in their thousands. The crocs snap up the old, slow, injured and new-born. At night, the cats and hyenas stalk both banks. It is Africa’s greatest spectacle.

We drove through the migration, cutting slowly through the moving lines. If allowed, your car can stop and you can get out, standing tightly against the vehicle. If you do, will see wildebeest all the way to Earth’s horizon. You will feel the ground trembling beneath your shoes, as the pounding of two million hoofs shake the soil. You will hear the non-stop bawling of thousands of wildebeest mothers, calling out for their thousands of new-borns to keep up. And for just a moment. You may feel part of something larger than yourself.

Serengeti: Lion Day

Serengeti (In Maasai Language: ”The endless plain”) is world-famous for lions. It holds 300 lion prides, with 15-20 lions in each group. That means up to 6,000 total, or 50% of the lions on Earth. Lions talk to each other. If you listen, you hear roars, grunts, moans, snarls, growls, meows, puffs and even woofs.

They also change color. Cubs are born with bright blue eyes, which change to amber (or brown) after 2-3 months. Finally, they play. Cubs bite ears, pull tails, cuff faces and jump onto backs and chests, just for fun. Adults do the same, but lazily. A male will bite the neck of a sleeping female. She will wake, roll over, cuff him off her and go back to sleep.

Adult lions, sadly, pose problems for tourists. They sleep 20 hours per day. They hunt at night, failing to kill in 75% of their attempts, but following the same animal, over and over, until they eventually bring it down. Having eaten, they drink. Having drunk, they sleep—just when eager tourists come bursting out of their luxury lodges to photograph them killing things.

We saw lion after lion, all asleep. The first two were 13 feet high in a tree. Both lay on branches, one branch above another, paws dangling down. Both were asleep. Then we found five golden males, all sleeping on their backs, legs sprawled in the air. Wait. . .what? That was not why we came to Africa. We wanted them to get up and jump on one of the two million wildebeests. However, none did, so we watched them sleep—and got sleepy.

One lioness slept near a thornbush. Our guide, no doubt using x-ray eyes, told us that the thornbush was filled with cubs and that if we waited, they would eventually come out and play. We waited. . .and waited. . .and the sun dropped low.

Then, amazingly, one little orange head poked out of the thorns, peered around, saw us, and ducked back. Ten minutes later, it tried again, easing slowly out of the bush. It was followed by #2 and #3. Once out, they looked around, to locate their sleeping mother. Then, #1 jumped on #2, knocking her over and pulling her ear. #2 cuffed him hard on the head, knocking him backward. #1 then jumped on #3, who grabbed his tail—and so it went.

Unexpectedly, an equally tiny hyena cub appeared—with no mother in sight. It toddled unsteadily toward the three cubs, and we held our breaths. I wish I could tell you that they played together, or fought or even growled at one another. However, they didn’t. When they saw each other they all just crouched and stared.

The little hyena tottered away. The cubs climbed on their still-sleeping mother to bite her some more. As the sun tumbled down and darkness fell, all I could see with my pocket flashlight were three pairs of little blue eyes.

What Does All This Cost?

An African safari is like a Broadway show. To locate, watch, film and fully experience wildlife interactions (e.g. a lion-kill) every human actor (guides, drivers, cooks, etc.) must play his/her part perfectly. Every part of each day’s production must go just as the audience (the tourists) expect.

Production costs for each successful day in the wilderness include petrol for the land cruisers. Uniforms, rifles, and bullets for the staff as well as rain-wind-dust-elephant-and-lion proof lodgings and three splendid daily meals for the clientele. One must also include the salaries of every single person involved, plus the constant cost of vehicle maintenance on deeply rutted roads. I estimate that:

- A budget safari costs about $120-$150 per night.

- A midrange safari: about$ $300-$350 per night.

- A luxury safari: about $1500-$3000 per night.

Why Should You Go?

If you are African American, these magnificent animals are part of your African heritage. If you go on safari, you will learn a great deal about them. If that happens, you are likely to love them. That may lead you to want to protect them—each in your own way—from the invisible army of Asian poaching syndicates, who are hiring legions of African poachers to sweep across Africa, and eventually exterminate everything wild. Your efforts to do so—no matter how small they may seem—may provide you with a lifetime of satisfaction. You will be protecting your heritage.

Beyond that, would you not rejoice to visit a country where people actively welcome you, instead our American custom of merely being polite? In California, if a tourist asks a local for directions, he will receive them. In Tanzania (and across Africa), if a tourist asks directions, someone will take him to wherever he is going—and then ask him for dinner. Why not go on an African safari where you can both watch African wildlife and make African friends?