WALK WITH THE ANIMALS—IN AFRICA?

But, will you be chased, tusked, horned, bitten, or even scared?

BY PROFESSOR JEFFREY FADIMAN, M.A., PH.D., DIP.ED (BRITISH)

“If a rhino charges, you will each run behind a tree,” the ranger ordered. “If the tree is bent, you bend. If it is small, kneel. The rhino must think you are part of the tree.”

Why did I suddenly feel huge, fat and slow? No way did I think any rhino would take me for a tree. The ranger was in South Africa’s Umfolozi National Park, created to protect the endangered rhinos of Zululand. I was one of six edgy tourists, preparing to walk with the Umfolozi rhino. To protect us, we had one ranger, one Zulu game guard, two rifles for emergencies, one radio for real emergencies and a backup helicopter if things got worse. It was very reassuring, but why was I not reassured. Why did I choose a vacation where you pay to feel scared?

Why does anyone pay thousands of dollars to go on Safari? To stare at rhinos? Not likely. We can do that in a zoo. To watch them prance around in nature? They don’t. Most stand still and chew grass, or sleep. Then why did I want to walk with them? Why would anyone want to walk with them?

Could it be that deep inside, we need to interact with animals? Dr. Doolittle could walk and talk with the animals. That’s why we all loved his books. As children, we wanted to do it too. Don’t we want to interact with other species—just a little—especially if they’re wild? Most of us are urban and not wild at all, but part of us still wants to be part of the wilderness, inside the picture and not just taking it. Walk with the animals? Love to.

TODAY’S SAFARI: A (NON) WILDERNESS EXPERIENCE

Africa’s wilderness is melting away, as the wildlife is steadily poached. Thus, the illusion that safari firms project to potential clients is melting as well. Kenya, for example, commercializes its safaris to where their wilderness experience resembles mass transit. Every morning, whole convoys of minivans, gaily painted to resemble zebras or giraffes, roam well-beaten paths in predatory packs. Drivers follow pre-set routes, often on pre-set schedules, having long since learned where each type of animal can be found and when.

Wildlife learns the schedules too. On Kenya’s Amboseli Plain, the few remaining cheetahs no longer hunt in late afternoon, when tourists go on game drives. Now, they hunt at mid-day, bolting their food while the tourists eat lunch. Then, they rest, and the drivers know where. No problem to find and photograph a sleeping cheetah. The tourists wish they would rise and run and hunt. Mostly, they don’t.

In Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater, drivers compete with one another along preset routes. Their goal is to spot Africa’s Big Five before the tourists go back for dinner. The safari experience has also become high tech. Each vehicle has a radio. If one driver sees something special, every other driver is called in to surround it. The goal is no longer to sit silent, watching big game do something beautiful as the sun sets; the goal is only to take pictures.

Thus, the peak of the commercial safari experience—say, sighting lions on their prey—may be noisily shared by a circle of mini-vans, each with its quota of chattering, picture-snapping tourists. Nor have drivers (with exceptions) developed much mini-van etiquette. With up to 9 vans surrounding each sighting, they compete to provide clients with closer views. As the vans press closer, motors throbbing, both the magic and the photos are spoiled, as the animals get nervous, stop eating and uneasily move off. Surely, there are better options.

WALK WITH THE ANIMALS? WHY NOT IN ZULULAND?

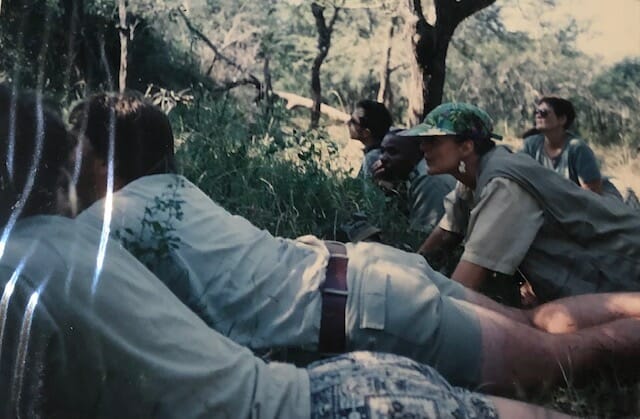

My wife and I wanted to find those options. We wanted to walk with the animals (or, at least walk near them), not just photograph them through a windshield. We also wanted both protection and training. We needed to learn how to act while on foot, not just around rhinos but every other animal. We needed a guide who could both teach us bush lore and carry a rifle. We chose South Africa’s Umfolozi National Park. At that time, it had about 3,500 black rhinos, 19,000 white rhinos, 96 other types of wildlife, 330 types of birds and 31 species of snake, including cobras and puff adders.

We arrived at a wilderness camp, with small tents, large cook fire, shovel ringed with rolls of toilet paper and a sign that told us to look for animals in four directions as we dug. The low point was a “bush shower”; a bucket with holes in the bottom, tied high in a tree. To intensify the experience you shower at night, when the cold air cancels the hot water and your imagination can populate the darkness with red eyes, crouched low and creeping closer.

We were joined by a ranger guide, a Zulu game guard, and four other tourists. Instruction began immediately. Lesson one concerned the previously mentioned need to “become trees” if a rhino charged. Lesson two stressed the need for immobility if no trees were around. “Animals see movement,” the guide instructed. “Freeze and you’re invisible.” Lesson three dealt with evasive action if we did get chased. “If a rhino gets close, wait till he drops his horn, then dodge left. His eyes will close and he won’t see you go.”

Outwardly confident and actually unnerved, I asked the guide if he had ever been charged. “White rhino won’t charge unless threatened, but black ones do, all the time. They want you to get away from them, so they go off like pop guns. Once I peeked over a hill, he added, just ahead of both the game guard and group, and looked square at a black rhino. We both jerked back in fright, but then she charged.”

I yelled at the group to take cover and freeze, he continued. The game guard stepped up beside me. We fired warning shots in unison. It ignored them and started down. The game guard took cover. I ran downhill, to lead it beyond the group. I remember thinking what a nice day it was except that I was being chased by a great, black rhino. When her horn dropped, I dodged left, but fell. The horn swished by and missed. Then, she ran right over me, giving me a kick. I got up, elated and—wham—went right over again, charged and speared by the rhino’s calf.”

We walked the ridgetops for three days. We wandered the Umfolozi River, while ripples of plains game ebbed away from our advance. Warthog, bushbuck, zebra and antelope would spot us, run, stop, stare back, then drift away. Soon we saw rhino. Bunching together like zebra, we crouched, crept, sneaked, stalked and tried to get in close. Then we froze, photographed and relaxed when we saw they were white. The first day, we stalked one. In the next two days we saw 21 more, all white. At one point, we were surrounded by them on three sides, each stamping, snorting and breaking up bush. Our only problem: white rhinos were everywhere black rhinos, nowhere. Privately, I began to hope we would find one and get charged.

That charge, when it finally came, was triggered by a yellow bird. We all noticed it, watched it land on a bush, then crept up to photograph and admire. Seconds later, a huge black shadow lunged out of the bush itself and charged the group. We fled to trees while both ranger and game guard raised their rifles. Both triggers clicked loudly in unison. Unexpectedly, the shadow jerked at the sound, swerved left and plunged away. Only then did I see it was a buffalo. “Luck”, the guide sighed. “Usually, they charge and charge until a man is dead.”

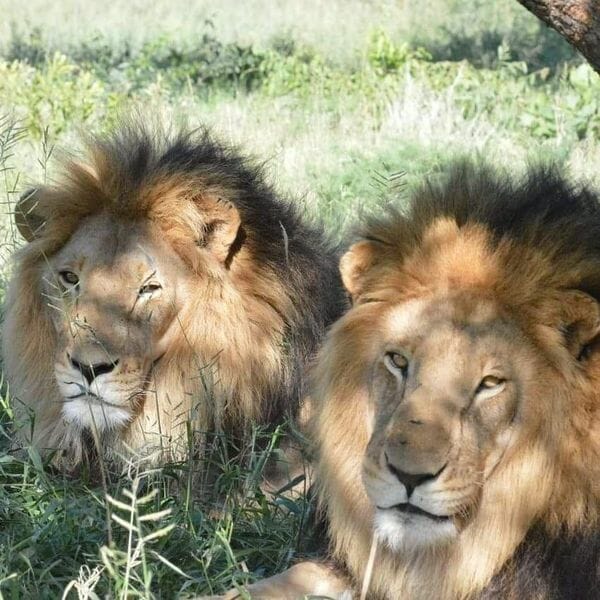

That night, at dawn, I dreamed I heard a Zulu shouting “20 lion.” I woke. The voice was our game guard. The words were “plenty lion” and he meant in the river reeds. We jerked awake, running riverwards dressed in cameras and underclothes, then stopped and stared. One lion, seven lionesses and a compliment of cubs ambled slowly by our group of sleepy, silent gawkers. Each group stared at the other with only mild curiosity. Jaded, both sides had seen it all before. Then, the lions wandered back into their reeds and the tourists wandered back into their tents and both groups went to sleep.

I went to bed but not to sleep. Last week, my major worry was making project deadlines. This week, it was evading rhino and worrying if “plenty lions” were sleeping too close to my tent. So, this was Africa outside the windshield. It seemed both more real, and more fun. A walking safari is not just going off the beaten path; it means entering a new dimension. We had not only left the safety of mass tourism; we had even left the safety of a car. In consequence, my wife and I learned a little more about each other and a lot about walking with the animals. And we didn’t even realize how much wilder it could be.

WILL THERE BE LIONS?