Out of New Bern: The African story of a descendant of slaves

The history of a little-known landmark of Black History and one of its illustrious children, Marva Louise Long

In an interview with The African magazine on January 31, 1996 in her cozy apartment in Accra, Ghana, her second post in Africa since she joined the U.S. foreign service in 1990, Marva Long said: “I’m happy that my ancestors were strong enough to survive over that trip. They were a very strong people to have endured what they endured.” Referring to her humble beginnings, she added, “If they hadn’t made it, I don’t feel like I would have survived. Even though we were poor, we had love, though I didn’t think much of it then.”

Love may have played a role in Marva Long and her seven siblings’ survival. But, what about the fighting spirit of the teenager who marched for civil rights and was teargassed and jailed? The tenacious, selfless single mother whose hard work paid off and landed her a job in the foreign service? Arguably, being born in James City, on the outskirts of New Bern, North Carolina, a land of renewal where the lives of thousands of runaway slaves blossomed anew, had something to do with Long’s journey.

New Bern, a landmark in U.S. History

When President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 that ended slavery, the Civil War was still raging. But the Union Army had already scored some crucial victories, one of which was to drive the Confederate forces out of New Bern, a major port city in eastern North Carolina at the confluence of the Neuse and Trent Rivers, in 1862. As a result, large numbers of slaves started to run away from the local plantations to flee to New Bern, where they were welcomed by Union Army’s authorities who treated them as free men and women, to the point of recruiting them in the army as early as the legal end of slavery in 1863. The impressive contribution of the so-called African brigade cannot be overstated.

The number of former slaves in New Bern increased so significantly that The Rev. Horace James, a U.S. Army chaplain who was appointed as Superintendent of Negro Affairs, established the “Trent River Settlement” where a newly created federal agency, the Freedmen’s Bureau, provided them with housing, clothing, and food. The Bureau established a hospital, while the American Missionary Association and other entities established schools. All things that held great promises for the future of men and women whose number was estimated to be about 3,000 by 1865. The settlement was renamed James City in honor of the Rev. Horace James.

In no time, James City became a burgeoning black town bustling with black business owners, farmers, religious leaders, and men with political ambitions who fought hard for their people’s rights. However, just a few years later, things took a bad turn as a result of the brutal, unforeseen economic circumstances experienced by the residents who also faced the reduction of government assistance. To add insult to injury, the owners of the land taken away by the government to create the settlement regained their ownership rights through court battles just two years after the end of the Civil War.

Once home and farm owners, the black residents became tenants forced to pay rent to white owners who were determined to kick them out of the town. The first of many to come in the cruel history of Blacks in the country, violent confrontations erupted between the black community and the white owners who increased rents unreasonably. The saga caused the black population to taper off gradually as many went to look for a better life elsewhere.

The Long family and New Bern

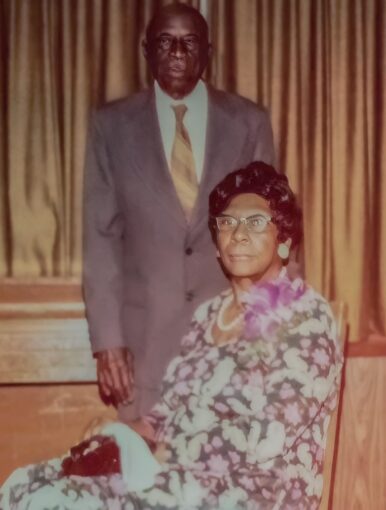

It was in this place filled with history, decades after the dashed hopes brought along by the abolition of slavery, that Marva Louise Long was born in February 1944, into one of the families that chose not to leave despite the hardships. Her parents were Isaac and Beatrice Moore Long. Beatrice Long was a housewife who worked in the homes of white people, babysitting and cleaning.

Born in 1885, Isaac Long did odd jobs, including raising chickens, working as a cleaning person in a company, and a handyman. He was also known as Santa Claus because of his generosity to children, bringing home from work popcorn and other goodies that most of the poor families could not afford. He lived a long, healthy life and passed away in January 1987, two days after his 102nd birthday. (Remarkably, at the age of 100, he was still healthy enough to travel all the way to Washington, D.C. to attend the high school graduation of his grandson Adrian, Marva’s son.) Isaac Long’s father, Jacob Long, was born on January 1, 1856. He was the first person to be buried in the James City graveyard which is now called Meadows Cemetery.

According to Ancestry.com and information that Isaac Long passed on to Marva Long, the Long family has very deep, traceable roots in New Bern going way before the Civil War.

Though he was a child back in those dark days, Isaac Long knew something about the tumultuous history of James City when the black residents refused to be walked all over by the white landowners. In an interview with The African in 1992 in James City, Marva Long recounted how her paternal grandmother, Ida Hassel Long, had to whisk her son Isaac away to a safe location during one of the multiple violent confrontations.

Setting the stage to connect with Africa

After three years at North Carolina Central University in Durham, North Carolina, Marva Long moved to Washington, D.C. to stay with her elder sister Shirley in search of employment. She quickly landed a job in the travel section of the State Department, which required taking a test that she passed. “I was kind-of smart!” she told The African with a laugh. So early in her career, she obviously had no plans—as yet—to travel to Africa. However, she shared with The African, “while sorting the passports to file them, I would always look at these applications and say, ‘maybe one day I can travel, get a passport and travel like these people are traveling. I guess that was just one of my dreams, that if they can do it, then maybe I can do it.’”

Typically, Long’s first job was not her dream job. To increase her chances, she took business classes in addition to hiking her typing and shorthand speeds. It was not too long before better positions came along, still in the civil service. She worked in different agencies of the U.S. government as administrative assistant for about two decades. Then came the idea to join the foreign service. It was like a walk in the park. In March 1990, she headed to her first post in Lagos, Nigeria.

Africa, here I come!

The negative portrayal of Africa is nothing new in the United States, even in the 1940s and 1950s when Long was a child. “The only thing you learned about Africa when you were growing up is you better eat all that food on your plate because the people in Africa were starving, not realizing that the John Doe down the street was starving also, but this was what they put into your head about the people of Africa starving,” Long said. Having heard a different story from many Africans she worked with throughout her career, she told The African, “I wanted to see for myself. So, when I joined the foreign service and received my first assignment, which was to Africa, I was elated.” She added, “The assignment afforded me the opportunity to see for myself and to be the judge of what I saw and did while there. Of course, there were some disappointments, but on the whole, the assignment was great.”

At the end of her assignment in Lagos in 1992, she served in La Paz, Bolivia from 1992 to 1994. Except for Bolivia, her career in the foreign service—mostly as the secretary of the U.S. Ambassador or the Deputy Chief of Mission—evolved exclusively in Africa. In total, if one combines her regular assignments of a two-year duration on average and the so-called “temporary duty” of several months, she has served in two dozen African countries which include, besides Nigeria and Ghana, Uganda, Mozambique, Swaziland, South Sudan, and Equatorial Guinea.

Fond memories

Marva Long has seen for herself that there is more to life in Africa than the abject poverty she had heard about from people who never even set foot on the continent. She has built personal ties in some of the African countries where she has served. “I have returned to Ghana several times and each time I felt welcomed by my Ghanaian families. They welcomed me with open arms and treated me royally during my stays.” Now retired from the foreign service, Long has taken several groups of American friends with her to Africa, including Swaziland. “The Swazi people that I had worked with treated me the same way. They were ecstatic to see me and gave accolades to my group that I had taken with me.” One of the fond memories of her assignment in Nigeria was to be invited to events organized by American women married to Nigerian men. She still remembers to this day the farewell dinner they gave her.

The wheels of History

After visiting some of the garden spots in the world—Paris, London, Brussels, and more—Long went back full circle—as History sometimes does—to James City and built her house on the same property where she was born 80 years ago. Indeed, that same place where she grew out of poverty through hard work, powered by the boundless love of her parents and siblings, and—no doubt—inspired by the courage she inherited from the ancestors who survived the hardship of the transatlantic slave trade and later refused to go down without a fight when New Bern’s white landowners taunted them.