Introducing Benin, one of Africa’s best tourist destinations

By Paul Sossou Guidimadjêgbê

Edited by Soumanou Salifou

GEOGRAPHY

Benin is bordered by Nigeria to the east, Togo to the west, Burkina Faso to the north-west, Niger to the north-east, and the Atlantic Ocean to the south. The total area is 114,763 square kilometers (71310.422 miles). It is roughly the same size as the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The population is estimated at 13.71 million (2023).

Benin’s official capital is Porto Novo, but Cotonou, the largest city, is the seat of government. The country is divided into 12 administrative departments: Atlantique, Ouémè, Mono, Zou, Borgou, Atakora, Alibori, Collines, Couffo, Donga, Littoral, and Plateau.

Based on the climate, November through May is the best time to visit Benin, when the chances of encountering heavy rain and extreme heat are at minimum. That being the dry season in the north, visitors have a better chance of viewing wildlife as the animals come into the national parks looking for water.

HISTORY

Pre-colonial Period (1600-1900)

The population of Benin is the result of three migratory movements that occurred between 1300 and 1600. It started with the arrival of Yoruba people from Nigeria, followed by the movement of the Ashanti people from Ghana. The third movement, which shaped the history of the small nation more than anything else, was the movement of the Aladaxonu people.

Having left Tado, in present-day Togo (on the west) following a succession dispute, the Aladaxonu, who descended from King Agasu, founded in 1600 the Kingdom of Alada under the leadership of their elder, Ajahuto. But the group split up again as a result of yet another succession dispute. So, Ganyehesu, Zanvo, Zonlo and Djegbo, all children of Dogbagri, followed their brother Dakodonou northward in search of a new home.

After several stops during which they overwhelmed the local populations with their hard work, war skills, and domination instinct, their journey ended in the Agbomê plateau where the local people, the Gedevi, gave them land to settle, with Ganyehesu as their king (1600-1620). Dakodonou, who succeeded Ganyehesu (1620-1645), asked for more land from the Gedevi chief, Dan, who insulted him. Dakodonou instantly killed Dan and had a tree planted in his belly, changing the Agbomê kingdom’s name to Danxomê, literally “in the belly of Dan” (in the local language, Fon). Later, the French colonizers, who didn’t know better, called it Dahomey.

King Houégbadja (1645-1680) decided that the Danxomê kingdom should continue to expand, with each new king leaving more land than he inherited. That led Danxomê to eventually conquer the kingdom of Alada in 1724, and the kingdom of Ouidah, with Savi as its capital, in 1727, which made Danxomê a regional power.

The 18th century saw the arrival of the Europeans in the area. The Portuguese came first, followed by the French, then the Dutch. Welcomed by the kingdom, the Europeans traded weapons for slaves, which, along with the prosperity it brought, helped the expansion of the Danxomê kingdom. With time, Danxomê spanned from Ouidah, on the southern coast, and northward to the area now known as Savalou.

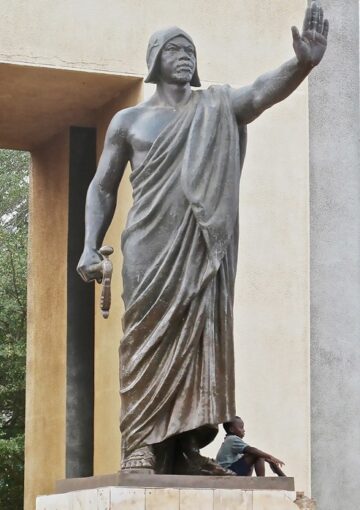

But the slave trade ended in 1848, sharply diminishing Danxomê’s military superiority over neighboring kingdoms. The kingdom adjusted by becoming a large exporter of cash crops under King Guézo (1818-1858) who later signed with the French a treaty establishing French protectorates in Cotonou and Ouidah. The French signed a similar treaty with the king of Porto-novo, Toffa, establishing a protectorate there, too. Guézo’s successor, King Glèlè, signed several commercial treaties with France. But King Gbêhanzin (1890-1894), who succeeded his father, King Glèlè, was rattled by France’s influence. He raised the tax for their occupation of Cotonou and wanted them out of Alada. Tension rose sharply, leading to the Danxomê’s war of resistance against French colonization.

The war was fought in two phases. The first phase was short, but in the interim both sides prepared heavily for what was to come next. During the second war, which lasted from 1892 to 1894, Danxomê put up a ferocious fight, forcing the French army to pull back several times. The French came out victorious in 1894. After going into hiding for a while, Gbêhanzin turned himself in and was deported to Martinique. His brother Agoli-Agbo, whom the French installed on the throne under their control in 1900, was deported to Gabon. This marked the end of Danxomê, one of several African powerful kingdoms that ferociously resisted French colonization. It was governed from then on from Paris through a local governor.

Colonial Period (1894-1960)

France’s appetite for expansion in the area did not stop with the demise of Danxomê. The colonial power conquered all the kingdoms up north, some of which resisted but ended being defeated. In the end, the whole area known today as Benin became a French colony in 1900, placed under the regional governor in Dakar, Senegal. Because of Danxomê’s military and economic clout, the colonizers named the entire colony Dahomey.

Thanks to French President General Charles de Gaulle’s decision to decrease the role of French colonial governors after World War II, the Danhomean elites began taking part in the administration of their country, forming political parties and trade unions which represented their interests in Paris. In a referendum held on December 4, 1958, Dahomeans voted to become a republic and elected Hubert Maga, a schoolteacher, as their president. But they had to wait two more years before becoming independent on August 1, 1960—albeit only on paper—as France’s barely disguised influence remained very strong, not just in Dahomey, but also throughout French former African colonies.