“Damn the Novel!” An author’s cry against a privileged genre

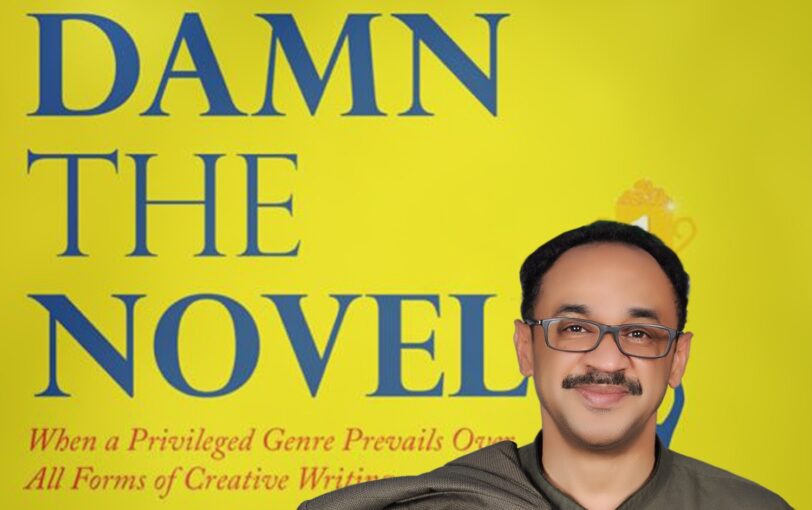

In a series of forty-five short essays that constitute his book translated into English under the title “Damn the Novel: When a Privileged Genre Prevails Over All Forms of Creative Writing,” Sudanese-born poet and essayist Amr Muneer Dahab denounces the privilege granted to the novel, the literary genre that is treated by publishers—and viewed by the public—as superior to all others and is virtually guaranteed marketability and profitability, to the detriment of others.

In this series of posts, the prolific author shares excerpts from the book.

This week:

Chapter 21

From Mahfouz to Al-Aqqad to Ali Al-Wardi

In his 1957 book entitled The Myth of Sublime Literature, the Iraqi sociologist Ali Al-Wardi wrote, “Many Arabic literature historians tried to explain that Arab people’s interest in poetry during the Pre-Islamic Era (Aljahiliyah) was due to geographical factors. Ahmed El Houfi, a professor at Dar Al-Ulum in Cairo, says: “Arabs are a poet nation . . . and the desert was of great role in flaring up this poetic tradition . . . there, the moon dawns smilingly and plainly, sending its silver lights upon the walking, the talking, and the wakeful people enchanting their hearts. Stars would sparkle movingly as if they were diamonds chanting whisperingly. All of this pushed Arabs of that remote time to shove off in expressing and revealing what was lying within their (crude) souls. Arabia is a land full of light where the sun casts its rays east to west. And light has a concrete effect on people’s attributes more than on their bodies. Goethe once said intoning the words within him: I want light! I want light!”

Al-Wardi directly reacted to the statement above using a sound sense of criticism: “Once I came across what El Houfi said in relation to Arabs’ poetic potency and tradition, I really couldn’t hold myself from laughing at such a pedantry. He is eulogizing the beauty of the desert; but he forgot what God has created elsewhere on this planet where wonderful settings also take the breaths. I wonder why people of Switzerland are not more poetic than the Arabs if nature is the reason behind poeticness? There are many others like El Houfi. They can easily find reasons for social phenomena the way they like. You can even see them come up with resonant expressions and strut as if they have already reached the peak of knowledge. Indeed, they are neglecting the concerns of society while they are chanting the moonlights, the sparkle of stars and sun movement from east to west, as if the sun does not carry on its east-west journey in other parts of the world.”

Al-Wardi then stated his thoughts about the spread of poetry among Arabs. The comment of Al-Wardi, with that bantering tone, can be summarized in one sentence: The beauty of the desert cannot be the cardinal reason for the Arabs’ love of poetry and their excellence in it. That’s because every part of the world (Switzerland, for example) has its own original beauty. Perhaps the most eminent conclusion we can take from El Houfi’s (unique) discovery is that most of the scholars are attempting to interpret literary phenomena; they cannot rest until they come up with an explanation, even if it is made through twisting logic to squeeze out any potential commentary.

For Al-Wardi, the importance and peculiarity of poetry for the ancient Arabs lies in this statement: “Poetry was the most important, perhaps the only, creative activity for Arabs. The reason behind this is that they were travelling continuously. Besides, they were obliged not to carry heavy luggage during their voyages except for the most indispensable for their life in the desert. They did not know much about the arts of writing, or painting, or sculpture or music or any other type of creativity; because these arts need different and many tools while they couldn’t carry them during their long wandering journeys across the desert. So poetry was the only affordable art for Bedouins to perform—rhythmic utterances easily memorized and told without being in need of anything but the unbridled eloquent tongue to dive in the sands of imagination (desert).”

If Ali Al-Wardi seemed focused on the social dimension of Arabic ancient poetry, it is because he is not glorifying Arabic verse of that time. We see that his attitude complies with the view of Professor Philip Khuri Hitti: “Poems in the Pre-Islam Era were powerful in terms of linguistic texture, alive with its overwhelming emotions, but it was as well feeble in terms of originality of ideas and of inspiring imagination. Given to such defects, Arabic verse loses its value when translated to other languages.” In turn, Al-Wardi stated, “I think that this statement contains some truth. In that pre-Islamic era, poets should not be perceived according to the position poets occupy within a civilized community; pre-Islamic poets were, above all, warriors.”

Al-Wardi was daring (for the time) when expressing his opinions vis-à-vis social, intellectual, and literary issues. However, his points of view are not rooted in twisting logic, even though his words may be formed with some sharpness given the many enemies, both in doctrine and in reason, he was facing in midcentury Iraq.

Al-Wardi did not commit his thoughts, at least in his mentioned book, to valorize a certain literary purpose over another, despite the fact that his book contains more than thirty essays about various linguistic and literary issues. Even when he discusses “the concept of sublime literature,” he presents ideas that make any genre of literature sublime from his own perspective, in addition to the opposing views of the contemporary men of letters: “They term it sublime because it is beyond people’s perception.”

The issue of “social class” and literature was among the main preoccupations of the long essay that Naguib Mahfouz wrote to counter Al-Aqqad in the Egyptian magazine Al-Risala, ten years earlier than Al-Wardi’s book. However, Mahfouz and Al-Aqqad were trying to grant power to a genre at the expense of another, more than they were searching for what made both genres sublime.

Al-Aqqad, when summarizing his opinion about his granting privilege to poetry over storytelling, actually plays the role of violent critics against Al-Wardi. Such critics mainly base their critical model on strong emotions (not necessarily devaluing their intellectual status) during the assessment process. Naguib Mahfouz in turn did not stop at only defending narrative fiction through showing its vital importance; he went much further in revealing the supremacy of narration over verse to state that the story owns the absolute potency over all existing categories of art. Then he proceeded to explain that the reason for that absolute supremacy is what he termed “the zeitgeist.” He did not hesitate to refer to the epochs of poetry as the epochs of “instincts and myths” versus “the era of science, facts, and industry,” for which he distinguished the story as its undisputed master.

Al-Aqqad waged the war to support poetry, while Naguib Mahfouz replied that the story was the out-and-out master of all arts. So, the two reached extreme extents of bold statements, which Ali Al-Wardi has not reached with his rivals yet (Abdul Razzak Muhyiddin as an example) in their ongoing battle lasting ten years so far. Still, the daring of breaking through every issue shouldn’t be in any way the objective behind every literary dispute. Thereby, the grace of Al-Wardi’s battle, the least daring one to set a preference between the genres, is that it was concerned with specifying the abstract meaning of “sublime literature,” despite not being derived from an agreed-upon concept. This also should not necessarily be the main inclusion of every literary conflict.

Soumanou Salifou (administrator)

Soumanou is the Founder, Publisher, and CEO of The African Maganize, which is available both in print and online. Pick up a copy today!