“Damn the Novel!” An author’s cry against a privileged genre

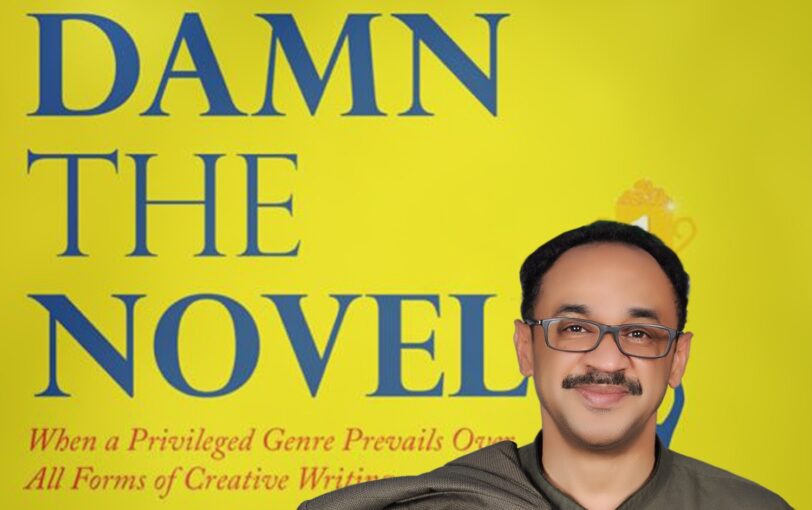

In a series of forty-five short essays that constitute his book translated into English under the title “Damn the Novel: When a Privileged Genre Prevails Over All Forms of Creative Writing,” Sudanese-born poet and essayist Amr Muneer Dahab denounces the privilege granted to the novel, the literary genre that is treated by publishers—and viewed by the public—as superior to all others and is virtually guaranteed marketability and profitability, to the detriment of others.

In this series of posts, the prolific author shares excerpts from the book.

This week: Chapter 19

Jack of All Trades

In reply to the view of Abbas al-Aqqad about the concept of favorability regarding storytelling and verse, Naguib Mahfouz wrote in the Egyptian magazine Al-Risala, 3 September 1945, Volume 635 (According to a Wiki resource): “Apparently there are other reasons to explain the noticeable domination of narrative fiction over all sorts of creative work. Perhaps the most eminent reason lies in what is now termed as the zeitgeist. Poetry has prevailed throughout the epochs when instincts and myths were the governing standards. Nowadays, the era of science, facts and industry inevitably needs a new art that can unite Man’s passion for facts and their inherited eagerness for fantasy. Thus narrative fiction (storytelling) has taken the lead. So, if poetry is being left behind in the race of popularity, it is because it lacks some aspects that will make it adaptive to the new era. According, storytelling has turned out to be the poetry of the modern life.”

The essay from which the above statement is extracted reveals that Naguib Mahfouz does not have any problem with expressing himself via this type of creative writing (the essay). It is also obvious when reading his essays in Al-Ahram newspaper half a century later; even though some critics suggested that those essays do not reflect the value of the novelist who, by that time, had gained much international esteem and fame. Naguib Mahfouz seemed to be devoted intellectually and emotionally to narrative fiction (story and novel) before the 1990s (perhaps long years or even decades before it). As a matter of fact, he generously (and somehow hastily) sent his essays whenever newspapers, including the prestigious Al-Ahram, sought the honor of publishing his words.

I do not believe Naguib Mahfouz has ever taken the essay into due consideration as an independent form of creative writing as much as the story and the novel. It cannot be even described as something that holds part of his concern for the sake of competition between literary arts such as poetry—especially given that we see him expressing, since the 1940s, his conviction about the absolute dominance of storytelling/narration not only over existing writing genres but also over all the forms of creativity.

I should underline the idea that Naguib Mahfouz of the forties seemed to be a better essayist than Mahfouz of the eighties. Perhaps the motive behind his mastery of essay writing, the above example specifically, arose from his enthusiasm as a promising writer who kept seeking the art (right path) whereby glory can be guaranteed, following in the steps of Al-Aqqad. However, Naguib Mahfouz, as the example above might prove, did not write essays beyond what was necessary (either as a reactive response when he was a young writer, or as an honor when he was a celebrated author). That was apparently the opposite of the valued consideration that the other novelists have allotted to the essay through successive generations in Egypt and other Arab countries.

What interests us the most in the above-mentioned essay by Naguib Mahfouz (in Al-Risala magazine) is the following paragraph: “Another non-less-dangerous reason is the flexibility of the story and its ability to accommodate all purposes. And that makes it a suitable medium to express Human Life in its full meaning. Thereby, there is emotional story, poetic story, analytical story, philosophical story, science story, political story, and social story. So perhaps the comprehensiveness of expression is more trustworthy than the two standards suggested by the great professor [what Al-Aqqad termed standards of medium and outcome]. It is plainly advocating that storytelling/narrative fiction is the most masterful literary art which the human imagination has ever created throughout all the epochs of Man’s existence on Earth.”

Naguib Mahfouz’s tone in the above statement comes with an ecstasy of victory and zeal for the new art that has invaded the “markets.” But what is strange is that the debate about the issue (the Era of the Novel) has been alive for more than seventy years now. It means that poetry, the novel’s obstinate rival, is actually more stubborn and too deep within the life of Arabs to be easily eliminated by a “new literary fashion,” a trend whose supporters thought would sooner or later overthrow its rival (namely poetry) with an unavoidable death blow. But what happened is that the novel, though widely spread, is still tottering in attempts to find some weakness in (the body of) verse so as to unseat it once and forever from the ethereal status it occupies in the consciousness of Arabs.

What about the claim that the story is compatibly flexible to fit all (literary) purposes? Poetry also can respond to all potential subjects: love, elegy, praise, pride, etc. If comprehensiveness (of subjects) matters, then it is possible for Arabs to retain the old lyric form and redefine poetry not by creating a new form, but reverting to how it used to be centuries ago, through reinforcing its comprehensive aspect that could incorporate even the histrionic ends. Thus, comprehensiveness is not a new invention attributed to the story as a unique and unprecedented literary phenomenon.

Besides, the ability to assimilate all the subjects (love, praise, etc.) is not considered a supreme value in itself. What matters most are the depth and the appeal of expression in the identified subject. And probably it is acceptable to claim the importance of having an emotional story, detective story, and social story, but some zealous devotees of the novel go to the extent of believing that one novel can accommodate all those purposes and more. And that has to be a defective exaggeration. One novel that contains all types that people long for as a portrait of life will be like a “literary cocktail,” something like a dish served hastily after gathering different foods and drinks to satisfy all tastes. But when that cocktail is compared to an “open buffet,” patrons will pick what they like without having to randomly fill their hands with whatever is available on the tables. The case is identical despite what may seem for some people as a tasteless comparison between the pleasure of food and the reading/assessment of literary pieces of work.

As far as cinema is concerned, some may even relate this “cocktail” philosophy to make the so-called Seventh Art not only able to cover all the subjects cinema can tackle, but all of the arts as well. It is such a daring one-upmanship with little beautiful creativity, but not enough to prove that cinema is the most dexterous art that humans have ever produced. It is not even enough to prove that it has absolute sovereignty over all the creative forms as Naguib Mahfouz did when advocating narrative fiction. The peak of what will come out from that daring one-upmanship in appreciating the value of cinema is a new form of “cocktail” for humans—a cocktail that endeavors to suppress all the existing forms of creativity through mixing and inserting them into its own plans of domination.

The value and the pleasure of any artistic or literary genre do come from their unique distinctiveness, not from taking all the light on the stage through pushing the other arts to the dark corners.

If the artistic/literary value depended on the ability to accommodate all the subjects or all the different literary genres in one crucible, I would not hesitate to nominate the essay as the master of all categories of literature. However, I will not do it due to a number of reasons. Above all, I do not want my charmer, the essay, to end as a new form of a literary “cocktail” awaiting eager “consumers” who would love to try new tastes.

Soumanou Salifou (administrator)

Soumanou is the Founder, Publisher, and CEO of The African Maganize, which is available both in print and online. Pick up a copy today!