Amendments to Benin’s constitution stir a controversy

BY SOUMANOU SALIFOU

COTONOU–BENIN: By a vote of 90 ayes and 19 nays, the parliament of the small French-speaking West African nation of Benin yesterday adopted several significant amendments to its constitution, stirring a swelling controversy both at home and abroad.

The landmark amendments provide for the extension of the presidential and legislative terms from 5 years to 7 years. They also provide for the creation of a senate consisting of 25 to 30 members, some “members by right” (former heads of state, chairpersons of the constitutional court, speakers of the parliament) and others who will be nominated by the president. Acting as a “council of the wise,” the future senate will be responsible for “regulating the political life for the sake of safeguarding and strengthening national unity, democracy, and peace.” Importantly, among other prerogatives, the senate will have the power to review, in the same manner as the head of state, any law voted by the lower chamber, with the exception of laws relating to finance and a few others.

A significant clause, which has apparently drawn the most ire, calls for a six-year “grace period” during which the opposition party cannot take initiatives likely to impede the actions of the executive branch.

The significance of these amendments registered with not only the political class and other opinion leaders but also with segments of the general populations, some approving the changes, and others disapproving of them, especially at a time when the current president, whose second term ends in April, has no plan to run for a third term.

The local media, definitely one of the most sophisticated in the region, rose to the occasion by dissecting the amendments, sharing in the process the reactions from both sides. A testament to the professionalism of the local media, even government-owned news outlets relayed the criticism. In an hour-long interview with Orden Alladatin, the chairman of the judiciary committee of the parliament, Benin TV’s veteran anchor Ozias Sounouvou had tough questions for the ruling party’s legislator.

Why the extension of presidential and legislative terms from 5 to 7 years, the reporter asked? To which the lawmaker replied by pointing out the need for a longer term for the executive branch to achieve the country’s development goals. Alladatin elaborated on President Talon’s “massive” achievements. (Even some of Talon’s staunch critics acknowledge the president’s impressive record in terms of infrastructural development not only in Cotonou, the nation’s economic hub, but also in the capital, Porto-Novo, and several other towns and cities. The International Monetary Fund recently ranked Benin as the African nation with the third best GDP growth in 2025, at 7%.) The lawmaker cited one project that required no fewer than 4 years to secure funding for. He emphasized that criticism of the legislative branch will be allowed, “but no public contestations. There is a lot to do, and urgently so, for the sake of stability.”

The reporter relayed arguably the worst concern of people who did not welcome the constitutional amendments, asking if the amendments do not hide the plan for President Talon to stay in power after the completion of his current and last legal term. Alladatin hasted to cite a clause of the constitution that reaffirmed the previous term limit: “No one in his life can serve two terms.” The interview then evolved around Talon’s decision to leave at the end of his term and the party’s choice to succeed him.

Several local scholars interviewed by the state-owned media and privately-owned ones applauded the amendments, contrary to others who found the timing suspicious. A scholar that The African could not identify pointed out on national tv the “universal” nature of democracy but stressed the need to adapt democracy to the specific context of a developing country like Benin.

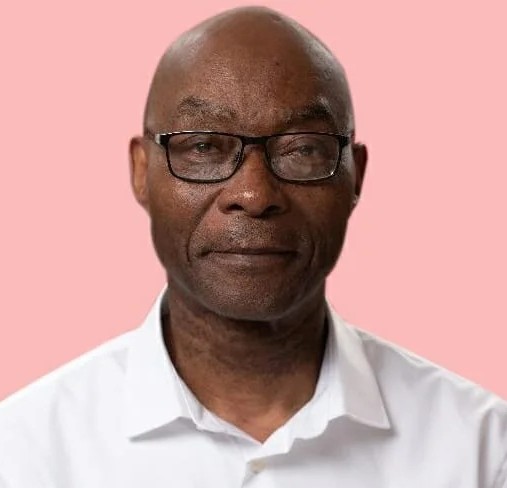

For another scholar, Edgard Gnansounou, Emerit Professor of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) and President of the international association Imagine and Building Tomorrow’s Africa (IBTA), the whole thing makes no sense. During the parliamentary debate leading up to the vote yesterday, Professor Gnansounou told a local news outlet that the constitutional amendment project attests to “the big ignorance of its initiators and its supporters about the deep significance of democracy for us, infantilized people.” Gnansounou’s biggest criticism has to do with the fact that the future senators will be appointed, not elected, in violation of international norms when it comes to the rule of law. Describing the constitutional amendments as the shipwreck of Benin’s democracy, the Switzerland-based scholar—the first and so far the only Black researcher to head the Bioenergy and Energy Planning Research Group (BPE) of this renowned institution often billed as the European equivalent of MIT—questions the presumed wisdom that former Benin heads of state and other dignitaries who qualify as “members of right” in the future Beninese senate would bring to the chamber: “Being a former President of the Republic or an institution does not really qualifies one as wise, especially in view of the intrigues that have always characterized politics and governance in Benin.

At the end of the day, these constitutional amendments, which are expected to be easily approved by the constitutional court, stand as yet another significant legacy of President Talon, the fourth man to lead Benin since the West African nation boldly kicked off the Africa-wide democratic movement of the 1990s with its unprecedented “National conference of the living forces of the nation” held in February 1990.