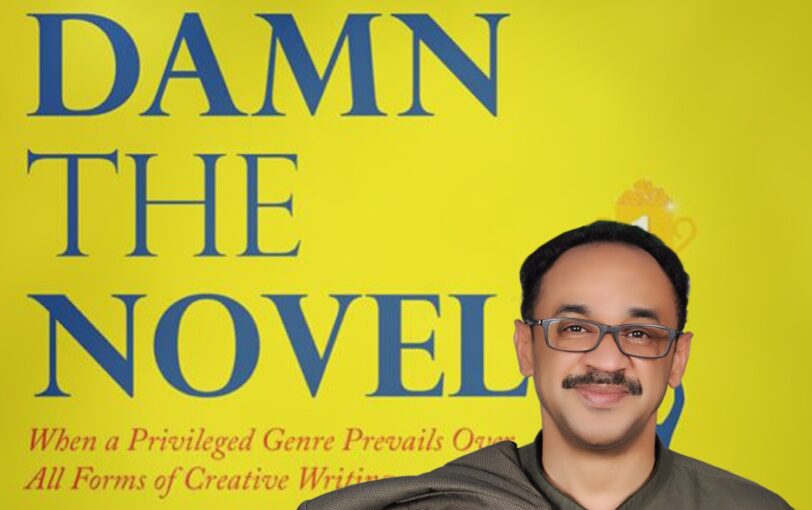

“Damn the Novel!” An author’s cry against a privileged genre

In a series of forty-five short essays that constitute his book translated into English under the title “Damn the Novel: When a Privileged Genre Prevails Over All Forms of Creative Writing,” Sudanese-born poet and essayist Amr Muneer Dahab denounces the privilege granted to the novel, the literary genre that is treated by publishers—and viewed by the public—as superior to all others and is virtually guaranteed marketability and profitability, to the detriment of others.

In this series of posts, the prolific author shares excerpts from the book.

This week—Chapter 3: Tayeb Salih Himself Might Have Protested

I can hardly name any critic who has dealt with Tayeb Salih without referring to the man’s scarce novelistic output or even accusing him of leading a barren phase of his life as a novelist shortly after Season of Migration. On the other hand, as we stated elsewhere, Alaa Al-Aswany has pointed out that scarcity is the rule when it comes to novelists (though I do not believe this applies to Al-Aswany), with the exception of Naguib Mahfouz and a few others worldwide.

Nonetheless, whether “novelistic scarcity” is the rule or the exception, creativity should be measured in terms of quality (how?), even when referring to one piece of work, rather than in terms of quantity (how many?). In this very context, though not being his only novel, Season of Migration is said to be a good illustration of how Salih could figure prominently in the Arab as well as in the global literary scene despite the fact that his critics kept awaiting a new tour de force equivalent to his previous masterpiece. They wanted concrete evidence to prove the man’s talent, and they received, in return, an embarrassing question: “What if I don’t write any more books?” The response arose of its own accord: “It doesn’t matter. One novel is enough.” In fact, Arab critics seemed to be the most obsessed with both the question and answer above, whereas great writers from all over the globe have always been valued by the uniqueness of a particular novel, rather than the number of titles listed in a writer’s resume.

I think Tayeb Salih was not the kind of writer to count exclusively on the greatness of one novel in lieu of writing successive pieces of work for the sake of some other instances of unique creativity. Alternatively, he insisted that he should keep himself away from (or even break up for good with) long fiction in order to embrace new horizons above “genre borders.” Short story writing was only an option, among other creative genres, coexisting with his (seemingly native) devotion to essay writing.

In spite of the truth about the smoothness of his novels and short stories alike, namely his masterpiece Season of Migration to the North, Tayeb Salih’s primary obsession consisted of, above all, his writing experience as an essayist. His essays were always the fruit of a sincere and deliberate inspiration free from the reins of any hasty assignment that would pay based on the number of words printed on columns limited in space. These essays were extensive in the eyes of readers and critics who evaluated his essays not by any drastic standards. However, Salih seems to have committed himself to essay writing being driven by the same respect he granted to his novelistic experience. The only harm that the man’s articles could have done is that they were provocative in the sense that they ruled out any possibility of a potential new novel capable of quenching the thirst of those eager devotees (believing in the novel for the novel’s sake).

What made Tayeb Salih an exceptional essayist was not only his encyclopedic knowledge as a well-read person who knew how to deploy the privilege of mastering both Arabic and English, but also his outlook on the essay as a majestic literary genre—not as a profitable routine that (might) help cover some of the basic expenses.

It is very unlikely that novelists can write exceptionally great essays if they arrogantly descend from their (novel) ivory tower believing in the simplicity of essay writing, whose supposed easy structure is perceived as rather an accessible genre unworthy of respect. Similarly, the novel knows well how to reinforce the same shortsightedness so as to trap dedicated readers (victims) into its snare.

Before being an honest writer, Tayeb Salih was an honest man. He ceased writing novels once he felt he had nothing new to tell through that literary genre; he never avoided being an essayist merely for fear of risking his reputable image as a novelist—losing the prestigious title by its being combined with, or replaced by, “essayist,” “columnist,” or, barely, “writer.”

Tayeb Salih ceases to write when he doesn’t have anything to say. Taking into account the man’s simple temperament, it does make sense when he sometimes resorts to silence despite having something to articulate. This is either because the events are worthy of much more than the usual approach or because the context does not allow the needed level of candor, whatever the form of expression.

Many critics would prefer if a number of writers could avoid producing pieces of work that were closer to redundancy than to creativity. Naguib Mahfouz was absolutely not among this category of writers. The Moroccan critic Said Yaktine smartly pointed out that the Nobel Prize holder was subject to a great deal of influence from Arab novelists throughout the eighties and seventies. This is a manifest illustration of Mahfouz’s intelligence and flexibility, which he should be credited for.

Compared to Mahfouz, Tayeb Salih did not only refuse to be affected by the mood created by the younger generation of novelists coming after him, he even did not let himself repeat the same novelistic experience he had once ushered in. Instead, he preferred to try something different or even cease writing for a while. It seems as if Naguib Mahfouz (according to the same comparison between the two great writers made by Yaktine) could not afford any good excuse or plan to dispose of fiction writing basically because he used to master/cherish nothing more than narrative prose among all forms of creative writing. This, on the other hand, might sometimes help writers multiply their output—multiplicity not as a defect per se, provided it is being done with care and expertise—and accordingly establish their independent approach to literature and art (creativity) in general.

If Tayeb Salih were not that well-mannered person armed with an economy of speech along with an unconditional devotion to and esteem for writing, I wouldn’t hesitate to imagine him turning on his heels were a narrative fiction devotee to inquire about the upcoming novel. He alternatively resorts to either a complete desertion of writing or an embrace of the elegant perspectives of essay writing. “Damn the novel!” he would cry out.

Soumanou Salifou (administrator)

Soumanou is the Founder, Publisher, and CEO of The African Maganize, which is available both in print and online. Pick up a copy today!