The importance of not being purely Arab

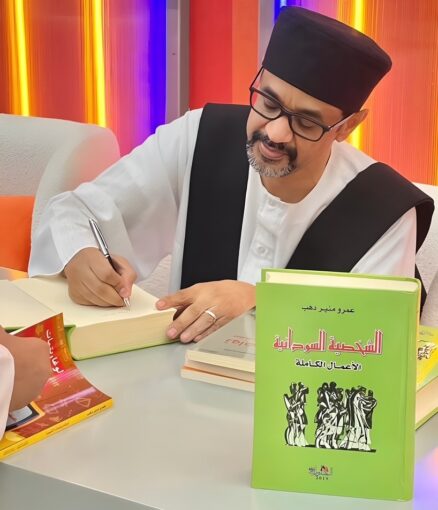

By Sudanese-born author Amr Muneer Dahab

Adapted excerpt from the author’s book “Sudanese Genes” published in Arabic in 2010 and included later in his collection “The Sudanese Character: The Complete Works,” published in 2019.

Images courtesy of the author

We often say that Sudan constitutes a bridge between the Arab world and Africa. But, in fact, we probably need two bridges: one to the Arab world and another to Africa. I have previously argued that to say that Sudanese belong to both the Arab world and Africa indicate a loss more than a reconciled blend.

Before rejecting my argument, one should first consider how Arabs and Africans view us, Sudanese, in terms of our dual affiliation. While Sudanese who reject my claim may be justified in doing so, based on how they are viewed by others, I want to emphasize here that this view does not necessarily confirm how a Sudanese is accepted on either side—Arab world or Africa—and how that ultimately contributes to a creative intermingling. On the contrary, the views of Arabs and Africans toward us (at their most optimistic or complimentary) amount to nothing more than partial acceptance on each side—a deficient acceptance; and when the debate escalates and optimism and courtesy are abandoned, partial acceptance—or deficient acceptance—turns into outright rejection.

What’s most important for us as Sudanese, before we dismiss the above, is to ask ourselves: what do we want from the research and the answers? If the goal is to spread optimism and inspire enthusiasm to affirm our allegiance to one group or the other, or to both, as the “rational” majority believes, then there’s nothing wrong with the research leading to something that inspires happiness and satisfaction and helps motivate enthusiasm in favor of either or both sides. But, if our search for a satisfactory answer is one that conveys no more than the bare truth—as much as possible—then the easiest and most worthy thing to do is listen to what others say about us, what those we claim to belong to say, those very ones to whom we go to to affirm that affiliation without looking around or reflecting.

However, we must be careful—before listening to those others—that the way we ask questions and receive answers does not stimulate or solicit a specific response, one of the kinds that inspire enthusiasm and incite a sense of happiness and satisfaction. It is not difficult to ward off a harsh answer if you have previously lined your face with signs of anger and disapproval in those situations. Nothing is easier than extracting a satisfactory answer with the “sword of bashfulness” held high over the necks of those you are courting in the same situations.

More effective than all the above, to discover the truth is to steal a look and eavesdrop. I don’t think we’ll emerge then without confirmation that Africans and Arabs alike pushed Sudan away much more than attracting it to them. The Africans believe that dark skin has risen above them after its color was “softened” by intermarriage over centuries; while Arabs believe that the “softened” dark skin has not yet risen to the level that grants it the honor of full integration into an already “soft-skinned” society.

This has been our situation, we Sudanese, as people isolated in a virtually remote place; we neither crossed the land separating us from full Arabism, nor did we leave anything with the Africans that would intercede for us and ward off the pitfalls of racial superiority under the pretext of Arabism in the event of confrontations and frank revelations.

The bottom line, then, is that we are no longer pure Arabs or pure Africans. However, the latter challenge is undoubtedly less serious, for Africa is not a single race or a specific cultural identity, but rather a collection of races and cultures united by what could encompass us if we were courageous to take the initiative and reject the arrogance that our centuries-long intermarriages with the “whiter” have tempted us with—a sentiment we do not like to confront ourselves about.

Moreover, Africa is a sense of belonging that does not cast heavy cultural shadows or even confusing political burdens; it is rather the freedom to belong and shape your belonging as you see fit for your present and history, as long as you live in that patch of land called the Black Continent. More importantly than all the above, African affiliation sees no harm in explicitly including Arab ethnic and cultural origins, provided that these origins possess the desire to initiate affiliation and the courage to reject arrogance before doing so.

Not being purely Arab is not a problem in itself, but it becomes so when we, as Sudanese of mixed races, insist on an affiliation that assumes, in all its forms—socially, culturally, politically, and otherwise—the elimination of any other identity and, moreover, even celebrates that sort of elimination.

The importance of not being purely Arab in Sudan is simply equivalent to the importance of understanding and living the truth. No one in the Arab world sees you as a purely Arab Sudanese, and there is historical, geographical, and biological evidence to support this claim. So why do you, as a Sudanese, insist on clinging to something that cannot withstand all of this?

Despite all that can be said about the pitfalls of discussing Sudanese identity and its complex calculations, the possibility of reducing the dilemma of Arab belonging in Sudan to a simple formula is probable: there is nothing preventing the elevation and celebration of Arab belonging, and at the same time there is no justification for denying other belongings—primarily those of African roots—and even celebrating them in a parallel manner as well, especially if our features and many aspects of our deep-rooted conscience point to that aspect of belonging indisputably.

_________

Amr Muneer Dahab is a Sudanese-born passionate essayist, literary critic and poet. An electrical engineer living in the United Arab Emirates, he juggles his professional career and writing, which has birthed so far 45 books. He is a columnist in several Arabic newspapers, and he hosts a weekly piece of Wisdom Literature, “Too Good and True, You Are Always Good to Go,” on the website of The African magazine.

__________

Dahab’s books are available on Goodreads and Booktasters are promoting them. This is the link to a trailer on “Damn the Novel,” his first book translated into English.

__________

To read more about the author, click here

Soumanou Salifou (administrator)

Soumanou is the Founder, Publisher, and CEO of The African Maganize, which is available both in print and online. Pick up a copy today!