The African Magazine at 30. Part III: it takes a village

It’s one thing to dream big and take the first steps on the journey to fulfilling one’s dream. At this point, one is still dreaming. But, when other people share that dream and, better yet, go out of their way to lend their moral and/or material support, that brings about an ocean of confidence that turns the dream into a reality within reach.

It’s one thing to dream big and take the first steps on the journey to fulfilling one’s dream. At this point, one is still dreaming. But, when other people share that dream and, better yet, go out of their way to lend their moral and/or material support, that brings about an ocean of confidence that turns the dream into a reality within reach.

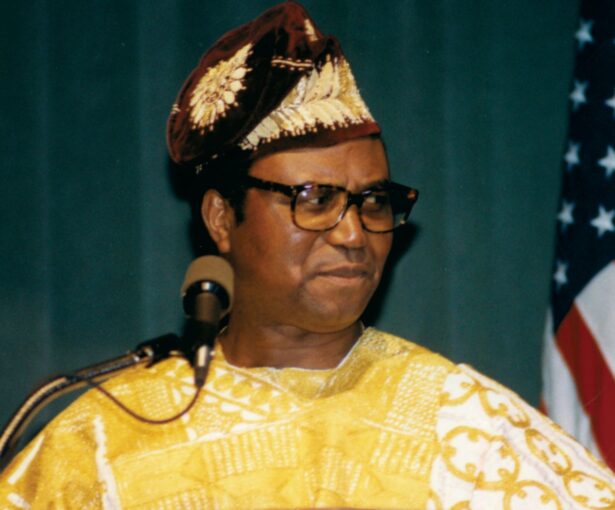

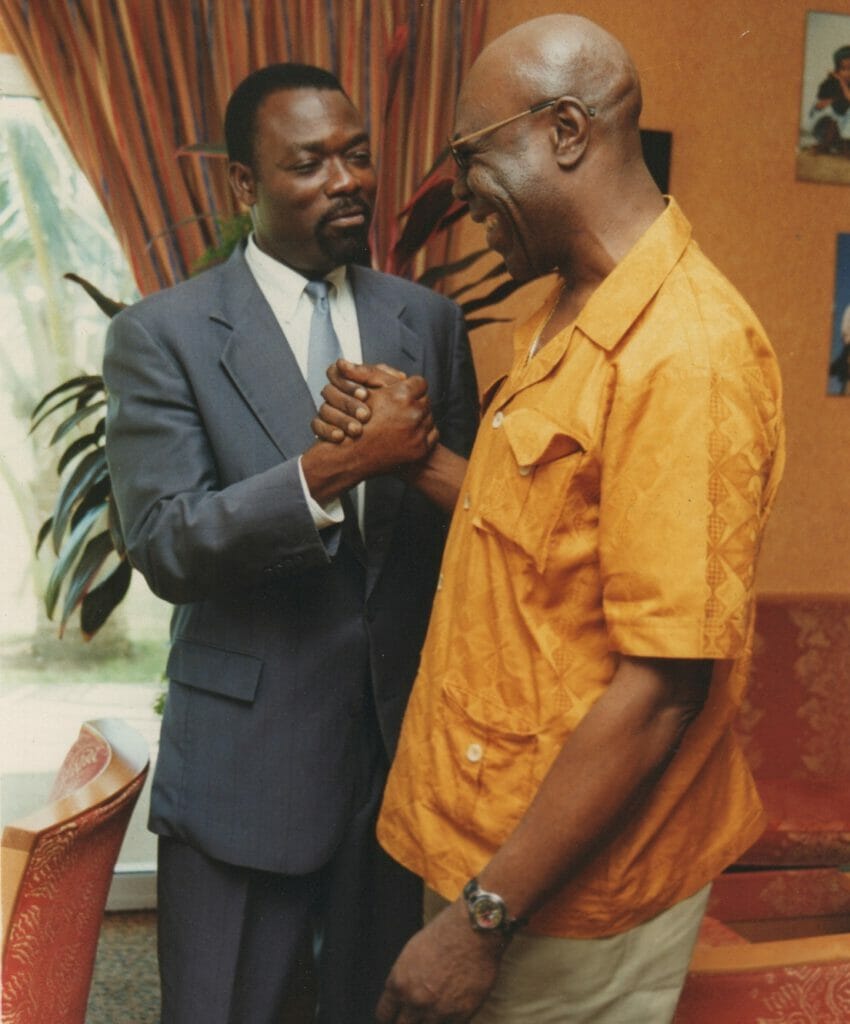

Benin President Nicéphore Soglo’s pivotal role

This magazine would not have come to life when it did and in the glamorous way it did on that memorable night of October 6, 1994, when the cream of the crop of Washington and New York had a piece of it, without then-President Nicéphore Soglo of Benin, my native country. After returning to Benin upon retiring from the World Bank where he had served as an administrator, Soglo was unexpectedly propelled into politics thanks to the historic National Conference of the Living Forces of Benin that tolled the bell of 17 years of a bogus Marxist regime that bankrupted the country. Soglo won the vote of the nation’s elite at the conference to form a transitional government responsible for running the country for one year while the new institutions of the future born-again republic were being formed.

In one year, thanks to massive foreign aid and investment that he eagerly sought all over the world, the former World Bank official began turning the devastated economy around in such a dramatic way that he won a full four-year term as president in April 1991.

Soglo, a long-time Washington resident whom I had known for years, did not frown on my offer, three years later, to help advertise his success and his plans in my dream magazine. After an extensive four-week advertising campaign in Benin during which I met with the president about a dozen times, I came away with a contract and a ton of materials to publish a country report covering all the key sectors of Benin economy, chiefly the Cotonou Port, the lynchpin of the economy. Payment had to wait until publication.

There is not a shadow of doubt that Benin got its worth from the 30-page reporting on its economy, with the president asking for several boxes to take with him to Canada, the next stop of his world tour right after the magazine was published.

Beyond the seed money that the reporting on Benin’s economy provided, the aftermath proved rewarding in other ways.

It meant a lot to this burgeoning publisher to know that the president was asked by the officials that met with him at his hotel after the high-profile launch of the magazine as described on page 10, to autograph the magazine. The next day, I was humbled to hear the president extend to me, in what was my first—but not last—phone call from a president, his heartwarming congratulations on “creating a much-needed magazine to tell the story of the new Africa,” along with his “strong encouragement.”

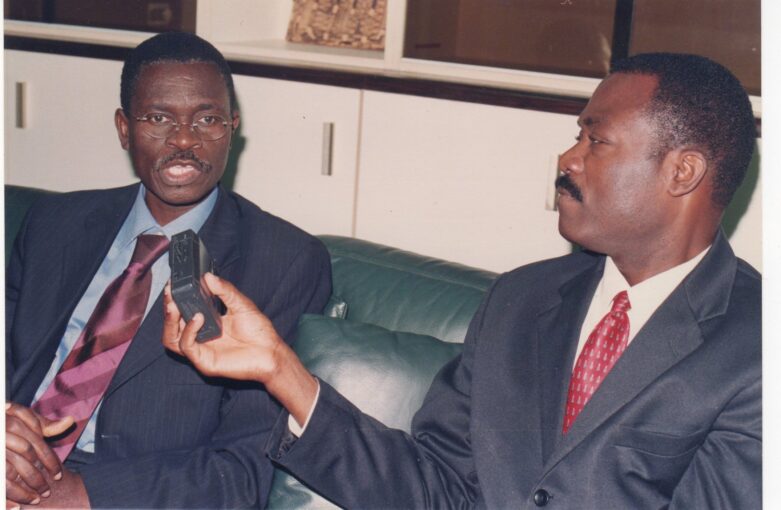

Two IMF friends who pushed the door open

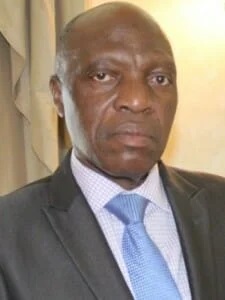

The initiative to go to Benin came from a Beninese friend, Innocent Diogo, a senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, IMF. After vacationing in Benin where he witnessed his friend and former IMF colleague Soglo’s quasi-passion to communicate about his plan to resurrect Benin’s economy, Diogo—who had helped me explore several investment opportunities to start the magazine that failed—enlightened me about what became a game-changer in my quest to publish this pioneering magazine.

Yet another Beninese national, Yacouba Fassassi, also a senior IMF economist who was “loaned” to Benin at Soglo’s request to serve as the chairman of the board of economic advisers to the president, played a key role in our advertising campaign. Acting as the president’s de facto communications director, he coordinated our vast reporting with all the necessary branches of the government.

A heartwarming letter from Fassassi also proved very helpful. “The need for African voices in the American media has become very pressing,” he wrote, adding: “We thus salute the promoters of ‘The African’ for launching this important tool of communication to get across the message of change. Calling The African “The Voice of Africa,” the brilliant economist wrote, “it is, no doubt, the missing link in our long-standing and crucial relation with America.”

The mighty power of encouragement

Over the years, my team and I have been uplifted again and again by the mighty power of encouragement of people from all walks of life, including a famous African ambassador on the world’s stage, mega entertainer Manu Dibango, whom I interviewed one-on-one in Africa in 2001. The long list also includes one of Africa’s finest economists, Christian Adovelandé, who served as chairman of two of the three development banks in West Africa (whom The African covered in both institutions), and Alhaji Ahmadu Adamu Mua’zu, the former governor of Bauchi, the northern Nigerian state The African has covered for years.

My son Samir Salifou, the best son any parent can ask for

My oldest son, Samir, was only 13 years old when I created The African. I was amazed how, at such a young age, he understood the significance of the magazine and the little spot such an unprecedented undertaking might earn our family in the history book. The support he brought to the business was equally above his age. As he grew older and more mature, he became Dad’s strategic partner in multiple ways. A true intellectual, he has written several powerful pieces for our magazine.

After Obama’s election in 2008, he wrote an opinion for our magazine titled “A campaign of wild emotions” in which he shared the scare Obama’s supporters had at the last minute as to whether their candidate stood a chance of beating his formidable opponent, the respected war hero and senator from Arizona, John McCain.

Four years later, after Obama won re-election in a landslide—not without frightening his supporters with his October 3, 2012, lackluster debate performance—Samir wrote one of the most beautiful opinions this magazine has ever published. It was titled “As Obama takes us to the mountaintop.” The essence of it was how Obama’s history-making victory in 2008 would have lost much of its significance in the eyes of the average American citizen if he had not won re-election. “Sure, on the night of November 6, 2012, the president would have ‘graciously’ conceded defeat and made a nice concession speech without shedding tears, with his family, aides, friends, and the rest of us pretending that it was okay, that defeat was a normal part of the electoral process.” Our young writer adds, “But Obama’s defeat would not have been the defeat of one man alone. He would have taken down with him an entire race spanning several continents.” Samir concludes, looking beyond the president’s reelection in November 2012, “Obama now has a chance to earn a spot in the exclusive circle of America’s greatest presidents and make us and the other several components of our diverse society even more proud of him, as he takes us to the mountaintop!”

That is not to mention Samir’s lengthy academic piece titled “The shackles of African neocolonialism” that we suggested to the African Studies Program of Boston University after we used it.

It will take an entire article to discuss Samir’s contribution as an unpaid amateur photographer, or how he advised me to keep the cuisine feature on the magazine’s menu when I wanted to discontinue it.

Though now pursuing a brilliant career away from our magazine, Samir remains emotionally attached to it.

My second son, Jonathan, despite not being closely involved in the magazine like Samir, did not stay on the sideline. When our team was in Harare, Zimbabwe in August 1997 to cover the Fourth African/African American Summit held there, it was Jonathan, then 13 years old, who recorded the entire closing speech of the summit’s convener, the Reverend Leon Sullivan, on which we based our final reporting of the mega event.

Jonathan, a very social young man full of energy who moves in many circles in Washington, D.C., later proved to be an aggressive, voluntary PR person for the magazine, taking it to important people and organizations.

My visionary sons Samir and Jonathan, two brilliant, ambition-driven young men who excel in their respective fields, gave real-life meaning to these words from the mouth of a character in the play “Le CID” by the great seventeenth-century French dramatist Pierre Corneille: “For souls nobly born, valor doesn’t await the passing of years.”

Despite being large and spread throughout most of Benin, the Salifou family, which has its roots in the historic, royal city of Cana, is probably not among the best-known families in the country, but it shines for one reason: it boasts many college graduates, including a dozen Ph.D. holders, scores of engineers and cadres who have held for generations high-level positions in the local civil service. My family has given Benin one of its finest scholars, Dr. Sahidou Salifou, holder of the highest post-doctoral degree in the French educational system, Agrégation.

It therefore came as no surprise that some members of my family understood the significance of me being inspired to start the first-known African magazine in the United States. Especially, my junior brother Bouraima, a much-traveled, fine intellectual whose early path in life was strikingly similar to mine—majoring in English like me, graduating from the same elite high school, Lycee Behanzin, and an alumnus of the University of Leeds in UK while I attended Johns Hopkins University in the U.S.—has lent a huge support in multiple ways from Day One.

Early architects of the editorial backbone

The African owes its editorial backbone not only to its dedicated top-notch writers, but also to several intellectual powerhouses—Africans, African Americans, and white Americans. Some of these fine people joined me when this magazine was nothing but a dream born in my mind, with no material resources yet to flesh it out.

At the beginning was a devoted colleague at the Voice of America, the late Nelson Brown, whom I hired as editor-in-chief. Nelson’s long evening hours at my residence after his exhausting day’s work, sharing the tiny computer that I acquired on a loan from my then-accountant, the late Mishel Kamara, helped shape the beautiful maiden issue. His reaction to the first issue is stuck forever in my mind. Holding it like a newborn baby that one is scared of dropping, he said, “This is very nice, and it will sell.”

Along came one of the most prominent African scholars of his time in the United States, the late Professor Ebere Onwudiwe, then-director of the National Resource Center for African Studies at Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio where he was an associate professor of political science. I put Professor Onwudiwe—who was found by Nelson—in charge a department that I created, titled “Ask Lady Africa,” to answer various readers’ questions about Africa, in the old days—1994—when there was no Google. The high volume of questions included the origin of AIDS, the physical characteristics of African people, and more.

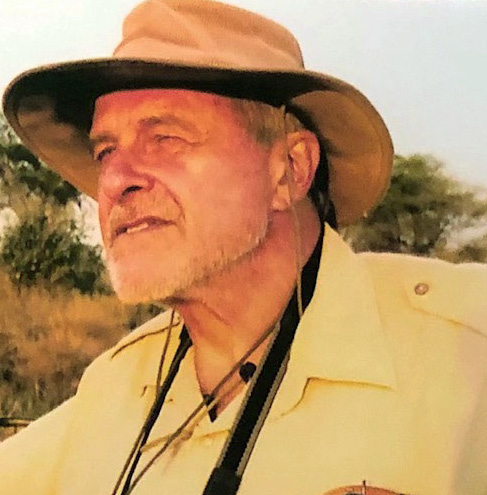

Decades later, like Santa Claus climbing down the chimney of The African house, a white American man in his eighties brought an immense reservoir of knowledge and experiences acquired in Africa for over six decades: Jeffrey A. Fadiman, a professor of Global Marketing at San Jose State University in California, a graduate of Stanford University who lived in Meru, Kenya in the sixties and was later accepted by the Meru tribe as the first White Elder of their nation. Fadiman’s fascinating stories written in beautiful, glowing prose that makes you want to read them over and over again, coupled with his occasional donations of cash, make a real impact. “Just a small donation nowhere near what you need,” he always says, underestimating how much a single penny helps.

Lately, African historian, TEDx speaker and best-selling author Emmanuel Kulu Jr. has been building on the foundation laid by previous scholars with a new series of authoritative stories on African history, substantiating Africa’s massive contributions to world’s history so vastly unknown or simply ignored in the United States.

My go-to supporters

Would-be-entrepreneurs sometimes go to their rich friends or relatives to ask for help to start a business. Saturnin Agbota, my childhood friend of 59 years, a self-made man and one of the premier businessmen of Benin, was that person for me. Due to unforeseen circumstances, he couldn’t help me raise the initial capital, but he helped significantly—financially—at a later stage.

Throughout his more than five decades in business, Saturnin has faced a slew of colossal challenges, all of which he has survived, like they were nothing! Having so closely observed this business acrobat always land on his feet, when I face challenges that appear unsurmountable, I tell myself, “Saturnin has climbed mountains higher than this!”

Africans usually call each other brothers or sisters when they meet away from home. I developed such a close relationship with a brother from Senegal, Idrissa Seydou Dia, who joined the Voice of America several years before me, that we were like blood brothers. I remember the shock and the unspoken doubt of several V.O.A. colleagues when I was bold enough to quit a well-paid job to venture into the publishing business. When The African house experienced its first fire not long after its erection, Idrissa turned out to be the one who helped put it out.

The support of Marva Louise Long, another former V.O.A. colleague who became a close friend of my family and almost a second mother to one of my children, can be summarized by the story behind a decoration in her apartment. It’s the story of a man who, in his dream, felt abandoned by God during the worst of times. Walking alone on a beach, the man wondered why God did not keep his promise to help him at times like that miserable day. Then, the High Most told him that He did not abandon him; that the footprints in the sand behind him were not those of the man, but the footprints of God who was carrying the man on his shoulders, because the man was too weak to walk.

In my business pursuit, when I find myself walking alone on an imaginary, endless beach, drowned in the crashing waves of my business concerns and uncertain how to find a way out, that story reminds me that I keep walking because I am carried on invisible shoulders. I then remember my friend Marva.

Service providers in a class of their own

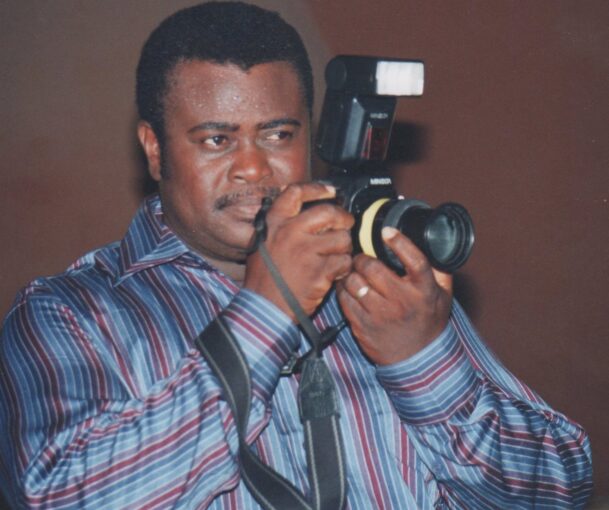

I have been blessed to work with some of the best professionals in their fields. One photographer that I met during an advertising campaign in Benin in 1999, Arsène Kasségné, whom I doubted at first because he shot everything and everyone faster than I had seen others do, turned out to be in a class of his own.

It turned out Arsène was not just a uniquely talented photographer. He quickly displayed a genuine interest in the magazine in good and bad times, not only in hopes of benefiting from it financially, but also to see it grow and prosper. We became like blood brothers! Besides my beloved son and cheer leader Samir, no other person in this world has so far been more physically and emotionally involved in the magazine than my buddy Arsène, the brilliant photographer who traveled all over Africa with me.

George Turner II aka Buddy Turner, my second designer, is another professional who has earned a warm place in my heart forever, with his name etched in stone in the humble magazine he helped me advance at a particularly tough time early in my business’ life. The hours I spent in his home office late in the evening after his day’s work watching him design the magazine are among the sweetest and unforgettable experiences of my professional life.

It’s in this village that my Godchild The African grew up, nurtured by the love and care of these good people. To paraphrase a proverb of my native country, “You have to lift it up to your knees before God can help you lift it up to your head,” I did the first part of the lifting, but The African would have been nothing but a dream without the members of the village whom I cannot thank enough.

It’s not a perfect world. In the village, there are also the doubters and the faints of heart who laughed at my “excessive optimism,” not to mention the predators—some too close to home—and the wicked who laughed when I sometimes fell but only to get up, dust myself off and try harder the next day. In a strange way, these negative souls driven by mediocrity have provided part of the fuel that has helped the ship to sail through the rough waters all the way to this port. Thank you.

As The African celebrates its 30th anniversary, let’s look to the next thirty years, the next important milestone where, hopefully, the flame will continue to burn, while I look down from heaven.