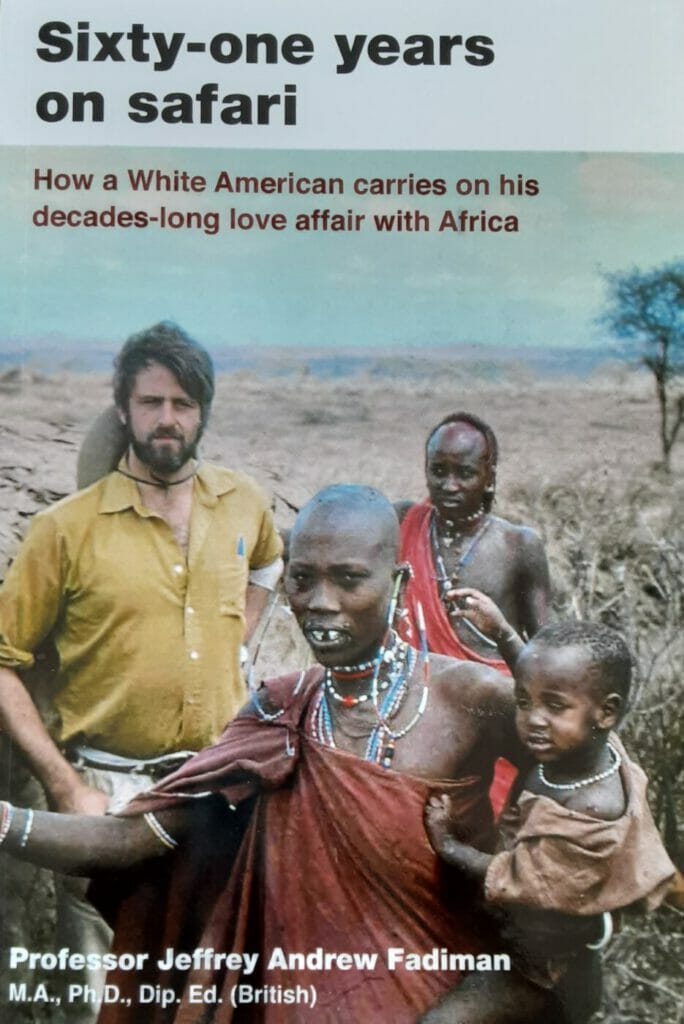

How a White American man tracked lions in Africa

In this new excerpt from his book “Sixty-one years on safari—How a White American carries on his decades-long love affair with Africa,” Jeffrey Fadiman, a professor of Global Marketing at San Jose State University in California, and a Language and Area Specialist for Eastern and Southern Africa, shares his hair-raising experience about tracking lions in Africa.

BY JEFFREY FADIMAN

And then there were the lions. Lions fascinate Americans. We see them as magical–but only in the wild. We can watch them in zoos, but there’s no magic in that. They just sleep. Instead, we pay thousands to see them in the bush but only the daytime in a car where we feel safe. However, lions just sleep in the African daytime too. Having killed at night, they gorge on meat, drink water and then seek out the shade of a bush. Creeping within it, they sleep and sleep and sleep—until nighttime, when we tourists must be back at the safari lodge for dinner. Tourists rarely get out of the car and walk with them. But we did once—almost.

One day, 11 lions killed a Kudu after sundown, only yards away from where my wife and I had camped. The roaring, as always, seemed to come at us from all directions. Nonetheless, we felt safe. A pop-up tent sat atop our land rover, where no lion would reach up for bites. Nonetheless, they kept roaring and a twist of fear hit us both as we lay in bed listening. We had booked a “lion walk” at sunrise, just we two and a ranger-tracker. It had seemed like an adventure when we did it, but then it was noon and now it was night and they wouldn’t stop roaring.

For the first time, we both actually thought about the grey, dusty Mopani Forest that stretched out in all directions from our camp. I hate Mopani Forest! The bush grows thick and thorny. The trees are grey, not green. Worse, they look identical—same height, same shape, no leaves. The land is flat; not a hill, not a dale. Once inside we could never get back, should the tracker fall sick—or be eaten. Why would we—or anyone—want to walk into that forest to look for lions?

This tracker was a silent, small, old man, holding a rifle that looked older than he. I asked how many bullets it held. “One,” he replied. I worried—privately of course—if that would do for eleven lions. My wife asked how many years he had been a tracker. “Many,” he said. Profoundly reassured, we followed him, outwardly brave and inwardly fearful. Out into the forest. We were tracking lions.

__________

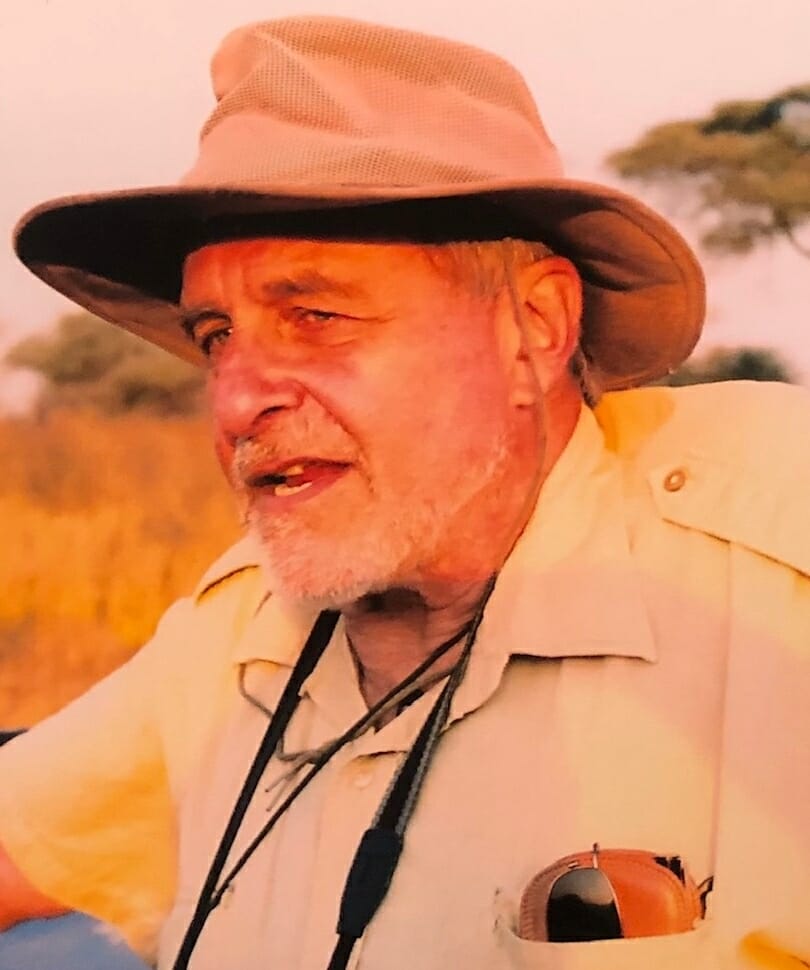

Jeffrey A. Fadiman, 85, is a professor of Global Marketing at San Jose State University in California, and a Language and Area Specialist for Eastern and Southern Africa. A graduate of Stanford University with two years at the Universities of Vienna and Free Berlin, this Fulbright scholar taught both U.S. and global marketing tactics at South Africa’s University of Zululand. He first experienced Africa in 1960 by canoeing up the Niger River to Timbuktu. Thereafter, he lived in Meru, Kenya, where he rediscovered the traditional history of the Meru tribe, which had been crushed by British Colonialism. Fifty years later, the Meru accepted him as the first White Elder of their nation. Professor Fadiman has supported both Tanzanian AIDS orphans and the schools to which he sent books, pens, paper, and hope.