WHITE SKIN/BLACK HEART

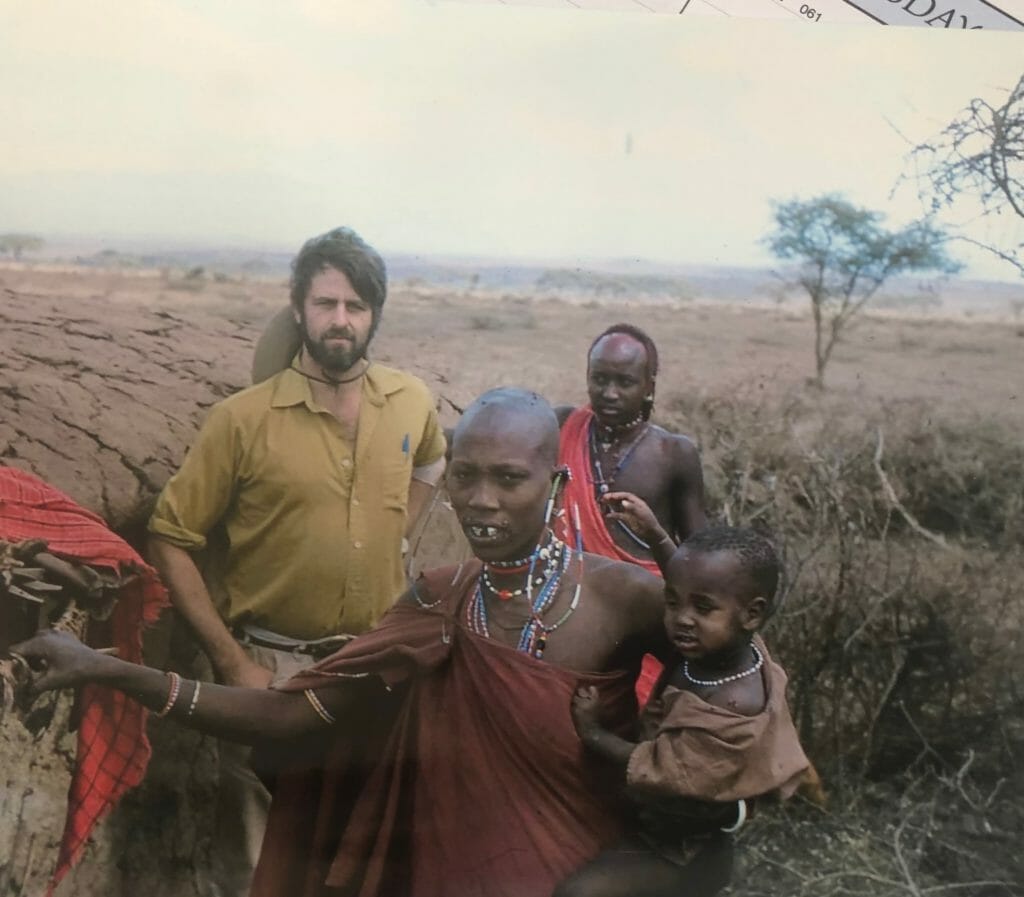

How a White American carries on his 61-year love affair with Africa

By Jeff Fadiman / Images by Jeff Fadiman’s friends

Jeffrey A. Fadiman, 84, is a professor of Global Marketing at San Jose State University in California, and a Language and Area Specialist for Eastern and Southern Africa. A graduate of Stanford University with two years at the Universities of Vienna and Free Berlin, this Fulbright scholar taught both U.S. and global marketing tactics at South Africa’s University of Zululand. He first experienced Africa in 1960 by canoeing up the Niger River to Timbuktu. Thereafter, he lived in Meru, Kenya, where he rediscovered the traditional history of the Meru tribe, which had been crushed by British Colonialism. Fifty years later, the Meru accepted him as the first White Elder of their nation. Professor Fadiman has supported both Tanzanian AIDS orphans and the schools to which he sent books, pens, paper, and hope. He’s excited to share his amazing love story with Africa—in his own words,

MEMORIES

Sixty years ago, I was 24, intensely single, underemployed and homesick for Africa. I had just returned from Timbuktu. (See “The African.” August 2021). Coming home had failed. I landed eager to share my adventures with friends. They were bored. Instead, they bombarded me with the parties, women and dope I had missed. I didn’t fit. I wanted out of here and back into there. So, I closed my eyes, held my breath—and JFK launched the Peace Corps.

The Peace Corps spawned smaller programs. I joined Teachers East Africa (TEA). TEA sent Americans to be teacher-trained for a year, then teach High School in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. The British, who ruled them as colonies, rejected U.S. college degrees. To meet British standards, they gave us British training, so we could teach African students to be British.

I was given a home where I could see fish eagles in the trees. They saw me too. The house came with a resident dog. As night fell, I entered the yard to toss it hamburger. Two Eagles dive bombed her. One seized the meat. She leaped at the eagle, snagged the meat, but was then knocked sprawling by an eagle wing.

The teaching was inspired, but the weekend safaris were magic. Once, two friends and I had camped and settled into sleep. I woke up near midnight, hearing something twang. Hearing it again, I opened the tent flap and peeked. I stopped breathing. An elephant was uprooting the bushes near our tent, his trunk brushing (and thus twanging) our tent peg.

My first reaction was idiotic: I grabbed my hunting knife, with some vague notion of stabbing the elephant’s toe as he stamped me flat. Next, I looked at my friends, happily asleep and not frightened at all. if I woke them, one would talk (or scream) and we all might die. So, they slept and I didn’t and the hours passed and I hated them both. Gradually, the elephant decimated the nearby bushes and moved off. The only mistake my friends made on waking, was to ask how I had slept.

As we neared graduation, the U.S. chief of TEA passed me a semi-secret warning: “Warn your Wednesday class. You have an in-class visit from the British Ministers of Education for Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. No one is supposed to warn you.” “Why me?”, I gasped. “Because they want to watch an American,” he replied.

Angry, I taught the Wednesday lesson on Tuesday, making sure they knew every answer. On Wednesday, with the Minister watching, I taught it again, snapping out questions, while my delighted students spit back answers. Afterwards, the Ministers awarded me any teaching post in East Africa. I chose Tanzania’s best high school, near Mt. Kilimanjaro.

HIGH SCHOOL TEACHER: MT. KILIMANJARO (TANZANIA)

The best school in British Tanzania was very British. On arrival, we Americans were taught that the British were to be obeyed. My headmaster was very British, as were the teachers. Things were done in British fashion; my job was to conform.

However, the African students were very African. They loved school. They loved every lesson and the worst punishment I could give was to expel one from class. That stunned me. Like other American kids, I had been taught to bad-mouth school. We weren’t supposed to “want” to go. We plodded through classes, living for the departure bell. African kids lived for class; they asked questions, made comments and thanked me for teaching them.

Their response to one assignment redirected my career. In those days, few Whites believed that Africans had a history. They believed Africa’s history began when Europeans arrived, did things, then wrote them down. Since Africans did not write things down, Whites assumed they had no history. I disagreed. To find out, I sent 12 students into their villages to “interview” their grandfathers about the tribal past.

The results were unbelievable. I expected every student to bring me four paragraphs. Instead, each filled entire notebooks: 30 pages of neatly printed, unknown tribal history—in pencil. Fascinated, I asked four to take me to their grandfathers. I met very old men who taught me histories for hours. I was hooked. This was fun. In my heart, I evolved from a high school teacher into an African Oral Historian.

AFRICAN ORAL HISTORIAN, MT. KENYA

I returned to America to struggle towards a Ph.D. My professors believed Africa’s history was locked inside the memories of African elders. As each died, their knowledge would be lost. The professors’ goal: to teach us to find and interview these elders, recording what they knew before their deaths.

I chose the Meru, a tribe on Mt. Kenya. I knew nothing of them, except a reputation for witchcraft—which my professors suggested I learn alongside the history. Thus, I timidly entered Meru to discover their past, dragging a reluctant wife, child and baby.

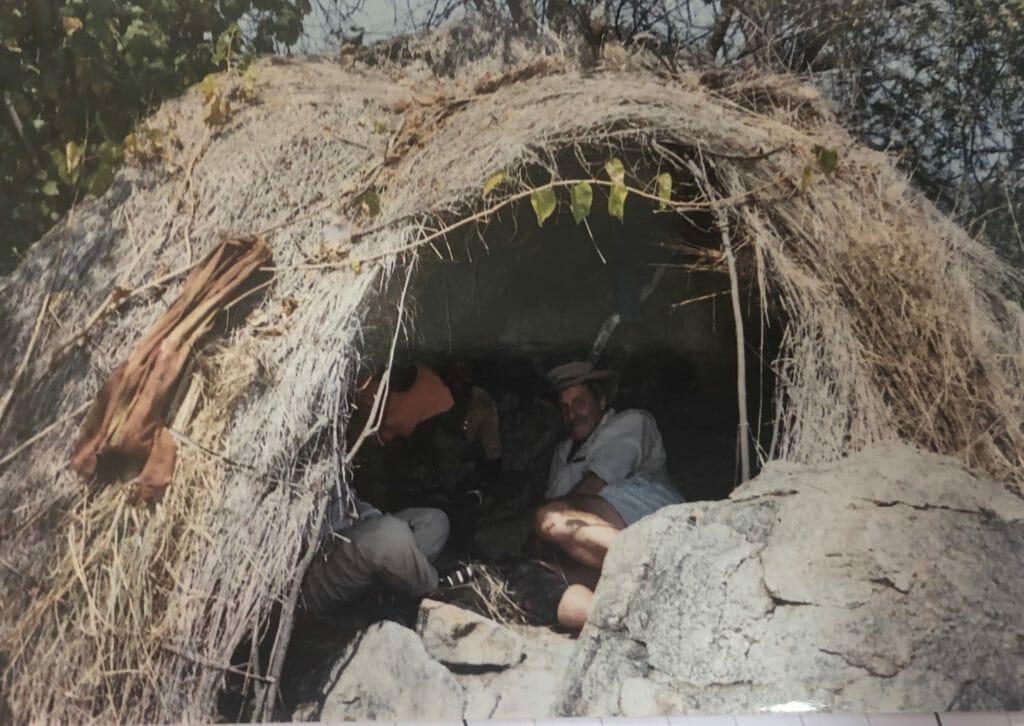

With no idea how to begin, I hired an interviewer and translator, then blindly struck out. Each dawn, my “staff” appeared with hot news: a traditional healer, or placer-of-curses, (i.e. witchdoctor), or remover-of-curses, (i.e. good witchdoctor) etc. wanted to meet me. Off we went, usually on foot. Each elder greeted us at his hut. Each received my gift: traditional chewing tobacco. I then explained the tape recorder, replaying his voice to show it was harmless.

My questions, however, were met by a deluge of narration as the past sprang to life in their minds, and they relived when they were young. Sometimes, an elder rose up and danced—then taught me to do what he was narrating. Over time, I became expert with a spear, war-club and fighting cattle-raiders. I also learned their witchcraft rituals, actually a system used to enforce traditional law.

Learning witchcraft proved useful to my family. My baby was two, an age when kids are carried on their mothers’ backs. For fun, Meru boys took turns carrying him on their backs around our house. One day, a 100-shilling note vanished from our table.100 shillings was a lot. I “hinted” that I would visit a witchdoctor to find the thief. That news spread everywhere.

I visited the ritualist, then made my complaint. He performed the rituals. Eventually, he divined that the ancestors knew the thief, but to tell me I must give him a goat. I agreed—if in exchange, he would curse the thief. I left. He gossiped. News that the White man was going to curse a thief went everywhere. Within hours, 99 one-shilling notes appeared on my table. Each nearby family must have contributed a shilling. They miscounted by one.

Each evening, my translator transformed the day’s interviews from Meru to English. I then reverently placed each piece of the story into sequence with others, a task that grew by the week and month to become gargantuan. I interviewed over 100 elders, over 300 times. Gradually, the entire traditional history of the Meru people unfurled before me like a softly-glowing flag.

Good things came out of this effort: one was a Ph.D. thesis, which became a book containing the entire Meru traditional history. More important, I began to think like a Meru. To understand Meru history, I had to grasp their culture. To do that, I had to learn how they thought. Everyone taught me without knowing how. I learned without knowing I was learning. Gradually, I just “felt” how people thought and knew what to do. It was only then that I heard the praise: “He has white skin, but a black heart.” (Since he thinks like us, there is hope for him.)

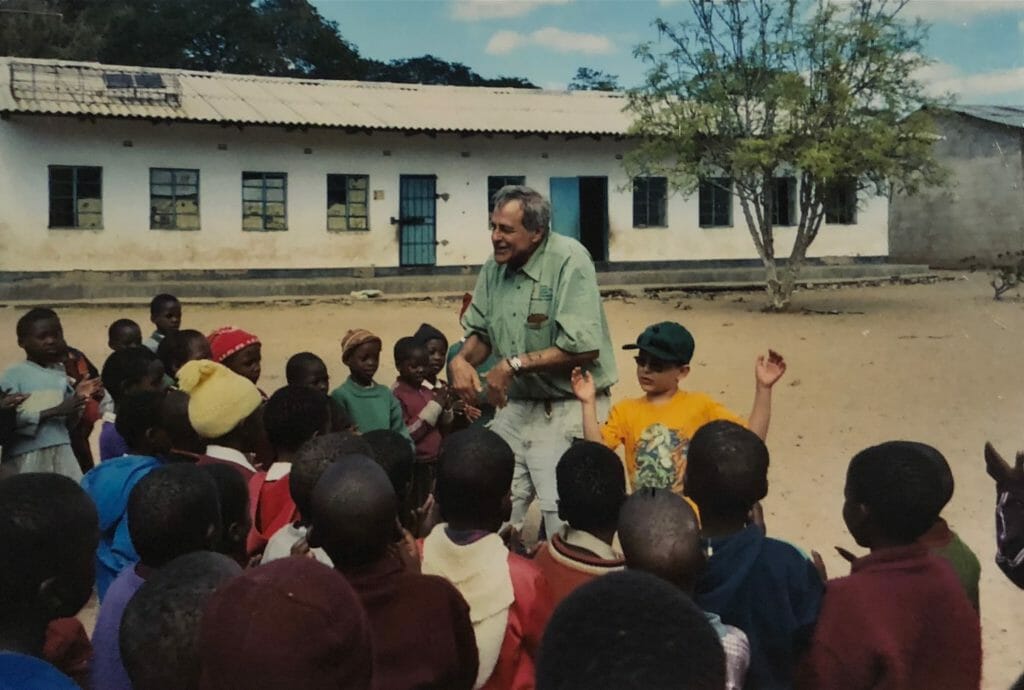

GUARDIAN ANGEL: BUSH SCHOOLS (ZIMBABWE)

Africa’s children need guardian angels, grown-ups who can hover over their schools and provide the learning materials that make education come alive. This seemed most true in Zimbabwe, where rural schools might have no windows or doors, and a blackboard might be pocked by machine gun bullets.

My tactic was to “adopt” one school at a time. On a first visit, I drove up, stopped and watched 300 kids boil out the doors and windows to greet me. I then shouted WHO WANTS TO PLAY SOCCER? and kicked a new-bought soccer ball. Three hundred kids chased it, and I was welcome at the school.

I then met the headmistress, head teacher, and selected pupils. Sometimes, I watched classes. Sometimes, I taught them. My goal was to learn what they lacked (books, pens, etc.) and provide it.

I focused on the grade that faced competitive exams at year’s end. My questions were always the same: Which subject is hardest? (Always, math). Which math book do you need?

How many? Can three pupils hold one book while you teach? How many pencils? Pens? paper, etc.

Ideally, I would leave school, drive to town, buy the materials, and return the next morning. In fact, nothing was easy. Roads to the schools were deep sand. School supplies were unavailable, thus requiring an order from the city. Orders were delayed or ignored. Mostly, however, things worked, and I could visit another school.

There were also lifetime benefits. Once, I taught in a terrible school. The headmaster often vanished. Teachers drank tea instead of teaching. The class I taught had no teacher. The pupils liked me, but two stood out. Instead of merely listening, they asked questions—good questions. They even followed me after class to ask more.

On a whim, I asked if they would like to go to a “good” school? Both said “yes.” If I find you one,” I asked, “and pay half your school fees, would your fathers’ pay the other half?” Both families eventually said “yes.” I found a good school. Both families kept the bargain, selling cattle to earn the fees. Both students studied, grew older, and advanced. Today, one is a dentist; the other does business—all because they asked questions in a class.

In-between schools, I often met wildlife with no fear of man. Once, my wife, small son and I lived in a well-constructed house-tent. One day, I saw a furry hand move under a corner of the house-tent and lift it. Silently, a baboon slid under the structure, went straight to the fridge and opened it. Clearly, he had come before. My wife and son were in the bathtub. I tip-toed in to ask if they would like to see a baboon in the kitchen.

“NO! GET IT OUT!” she shrieked.” “How do I get a baboon out of a house-tent,” thought I, “when I can’t lift the corner?” My answer lacked both subtlety and intellect. I threw a book at it, shrieked “BOO” and prayed. It grabbed the book, raised the house-tent corner and disappeared up a tree, perhaps to read.

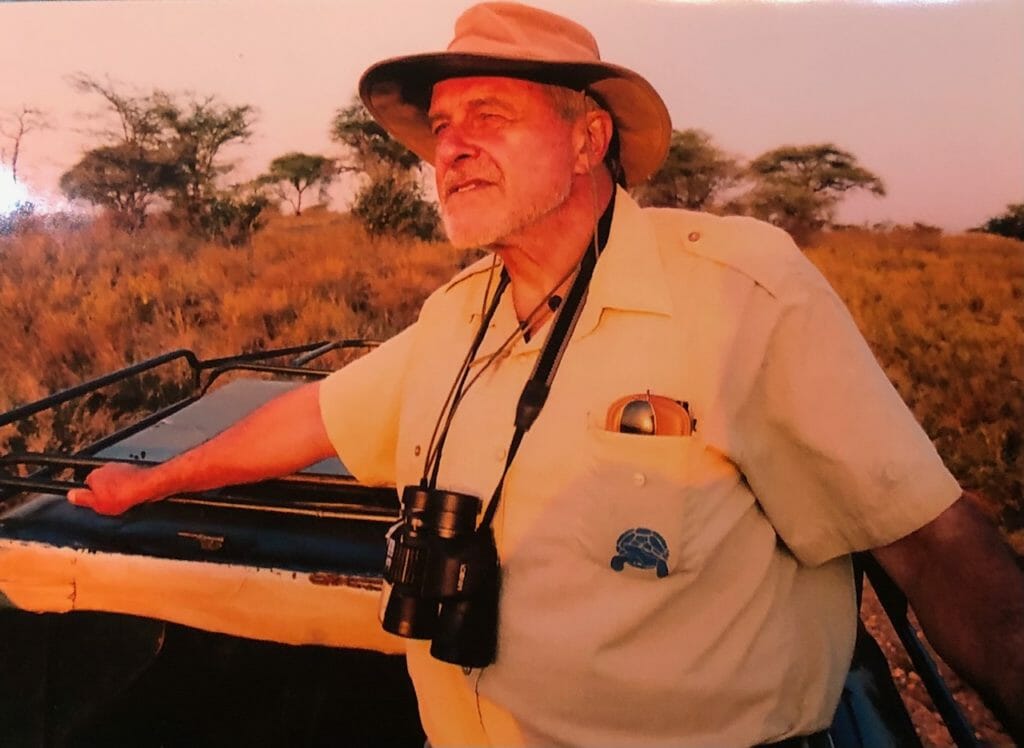

FULBRIGHT PROFESSOR IN ZULULAND

I returned to Africa to teach Global Marketing in South Africa’s University of Zululand (Unizul). My life changed. On a typical Unizul day, I woke at dawn. Seared by the rising sun, I entered the kitchen, only to be driven back by 100,000 army ants, trooping in a long, narrow column from a window into the stove. Jumping over them, I ate, went out and unlocked the 10 locks on my car.

I drove to Unizul, enthralled by the beauty of virtually everything; red earth, green sugarcane, cane-cutters waving as I passed. “How can I be so happy,” I once thought, “knowing everything is going to go wrong in 20 minutes?” I reached Unizul. I parked, attached my 10 car-locks, and hiked uphill to my office.

While climbing, I passed my students, lying in happy, chatting circles on the grass. “Class starts in six minutes, I called, “Come climb with me?” “Classroom is hot,” They called back. “Here is shade. You come here, sit down and teach!” They were right. However, I climbed, reaching the classroom just on time. Then, I stood, every day, hot, punctual and all alone.

They came eventually; polite, little groups trickling by me during the next hour—or two. Once, I got angry and pounced on some women, asking why they came two hours late. I never forgot their answer. “Don’t be hard on us, Prof. To come here we must climb one hill to reach the bus, which drives to the bottom of another. We climb that to catch another bus to come here. Then we climb the Unizul Hill to reach your class, and we are breakfast-hungry and the sun-hot, so we are slow.”

The women all weighed nearly 200 pounds. Climb steep hills? In hot sun? With no breakfast? I apologized and never asked about lateness again. These women were to admire.

Sometimes, however, we clashed. Everyday my classes filled. They sat in seats, on the floor, in windows, jammed in doors. The room roasted. Roll call was impossible. Written exams baffled me. Who did I give them to? Their pre-exam questions baffled me. “May we share the answers during the exam?” “NO!” I laughed. “That’s cheating.” “But Nkosi, (Sir)” came the patient reply “that’s cruel. We are all brothers and sisters. We want everyone to pass. Why shouldn’t we all help each other?”

That was a serious question, representing an African world view presented in an African classroom. I enforced my American world view and they took exams in a resentful silence. Nonetheless, I have thought about their question. If I ask American students “why” they cannot share answers on a test, they laugh, unable to consider any world view but ours. But what if the Zulu have a point?

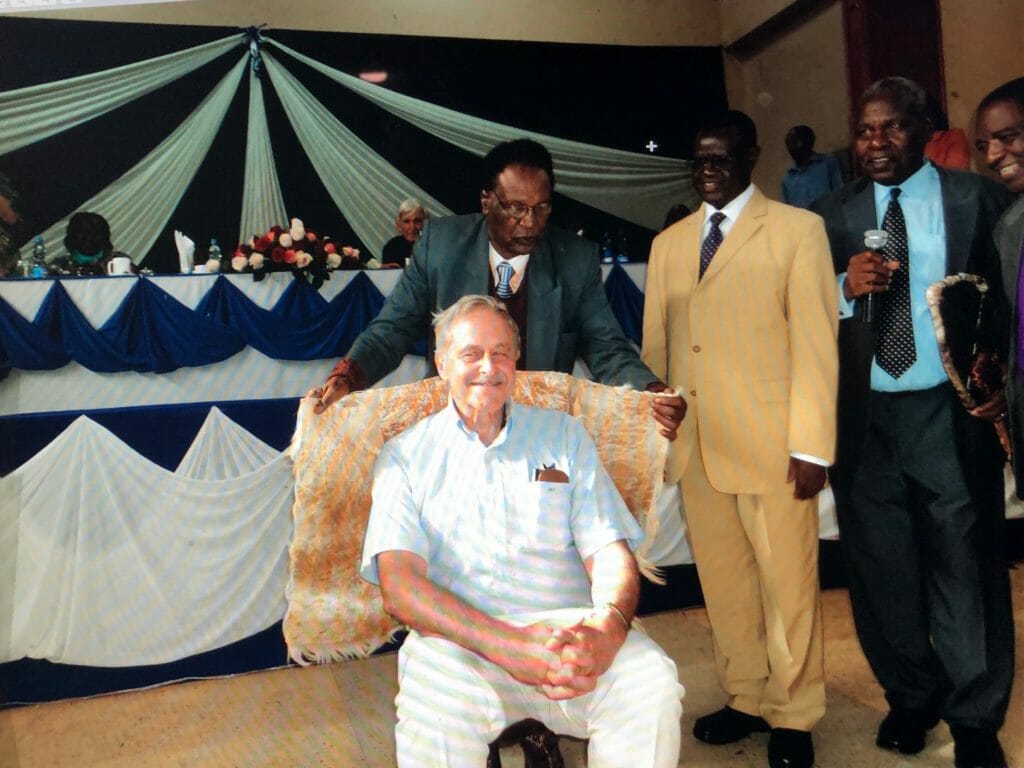

AN HONORED MERU ELDER

Fifty years had passed since leaving Meru. One day, the phone rang. “Are you the famous Professor Fadiman?” she asked? “I’m Jeff Fadiman, but not famous.” I replied. “You are—in Meru,” she answered. Is it you who rediscovered Meru history? If so, a Kenya Meru Minister asks you to email. He has just read your Meru History book. I emailed. He invited me to return to Meru, for the first time in fifty years, to be received into the Meru tribe as an honored elder. I accepted.

The day came. I was whisked to tea with the Minister and Meru members of Kenya’s Parliament who simply wanted to honor my having come. We moved to a great hall, where I was to speak on the Meru past. What I was not told was that I was 6th speaker, with five politicians speaking before me.

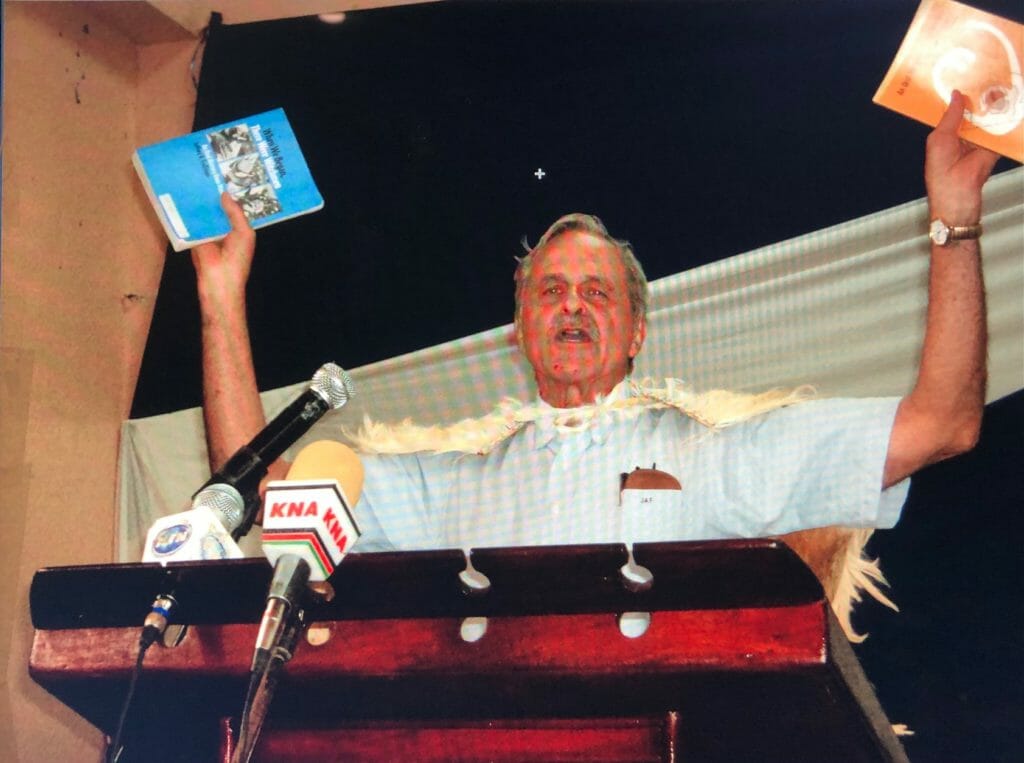

Two hours and four speakers later, I was too sleepy to be alive. Breaking every protocol, I poked the Minister, demanding three cups of black Kenyan coffee or I was going home. I finally spoke to a large audience of the most notable Meru. I described what I had done. I told them stories from their past. I dramatized the struggle their grandfathers had waged against British efforts to extinguish their traditional history, religion, marriage and other things that made them Meru. To end it, I said: “Fifty years ago, I listened to the grandfathers of everyone in this room. They taught me all they knew, but each—over 100 elders—asked me to write what they said in books, so that the words could tell their grandchildren yet unborn that they are Meru. These are the books (held high in each hand). You are the grandchildren. Now, read! Have I not kept my promise to your ancestors?”

There was standing applause. Then, they proclaimed me an honored elder, the first White member of the Meru tribe. It remains the greatest honor of my career.

Why don’t I retire? Abandon Africa? How can I? There is still so much to do. Won’t you join me? [Place la 4 aussi quelque part ici, mais jongle pour un bon espacement entre les trois dernières.